A Dialogue Between a Father and Son

A short story.

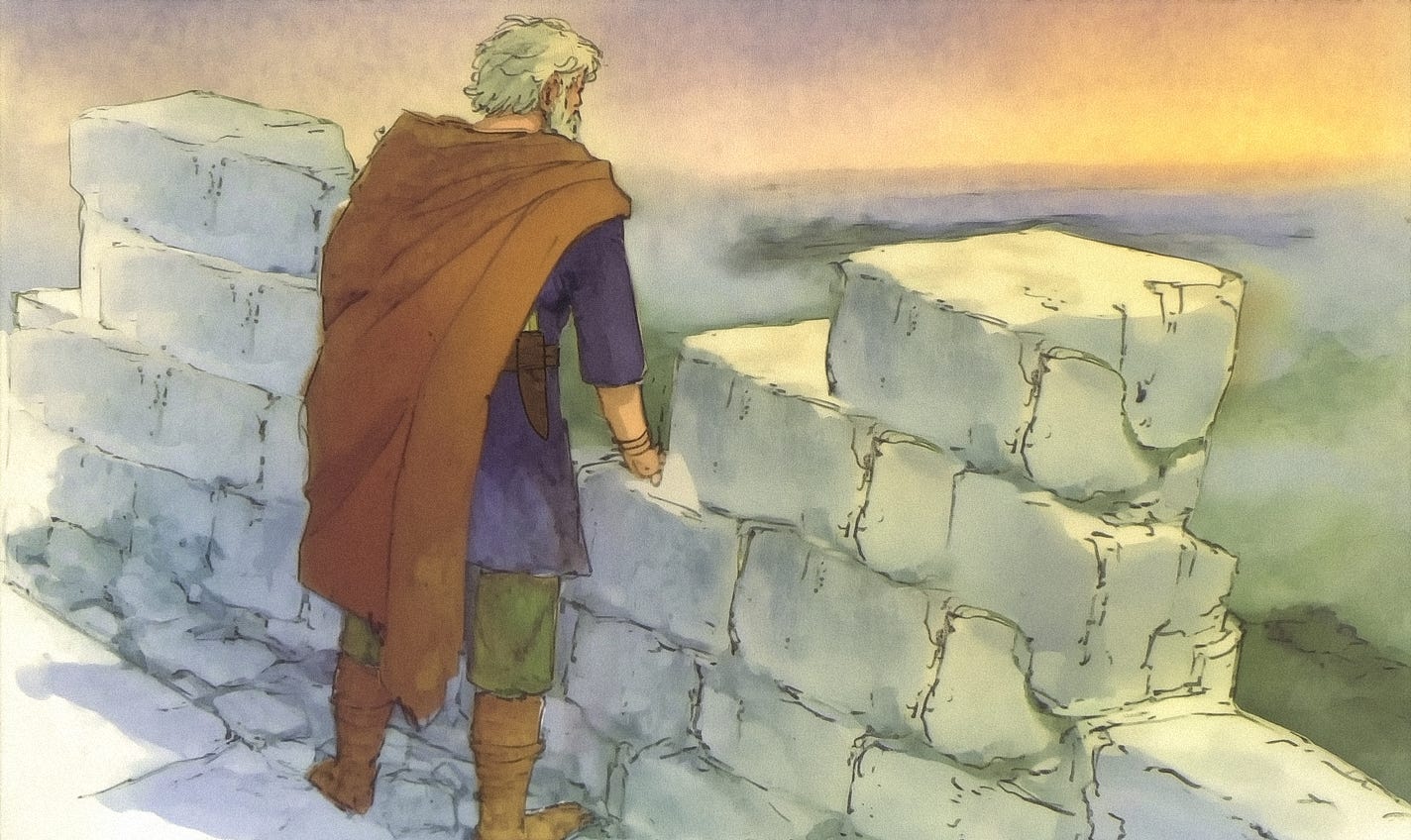

Urien stood silently upon the battlements of Catraeth watching the autumn mist roll low across the hills,the distant sound of hooves echoing. Owain was pacing, the leather of his boots creaking faintly on the stone.

“He’s crossed west again,” Owain said, voice low. “Riders saw Guallauc and his warband passing through our southern road. No message. No banner raised. Do we call that kin?”

Urien exhaled slowly through his nose, gaze not leaving the distant mist. “Aye. And you will treat him as such.”

Owain stiffened. “He pecks kingdoms like a raven pecks at carrion. He shows no deference. We hold the north together in uneasy truce, and he rides unbidden?”

Urien turned, eyes dark. “You speak as though you were not drawn from the same well. Do you forget who he is? Or who we are?”

“I forget nothing,” Owain replied. “But my patience frays. You treat him like a brother, yet he’s barely able to accept any peace.”

“No,” said Urien. “He is not. He was once. Or might have been.”

He turned back to watching the mist. Then he spoke, his voice quieter, older.

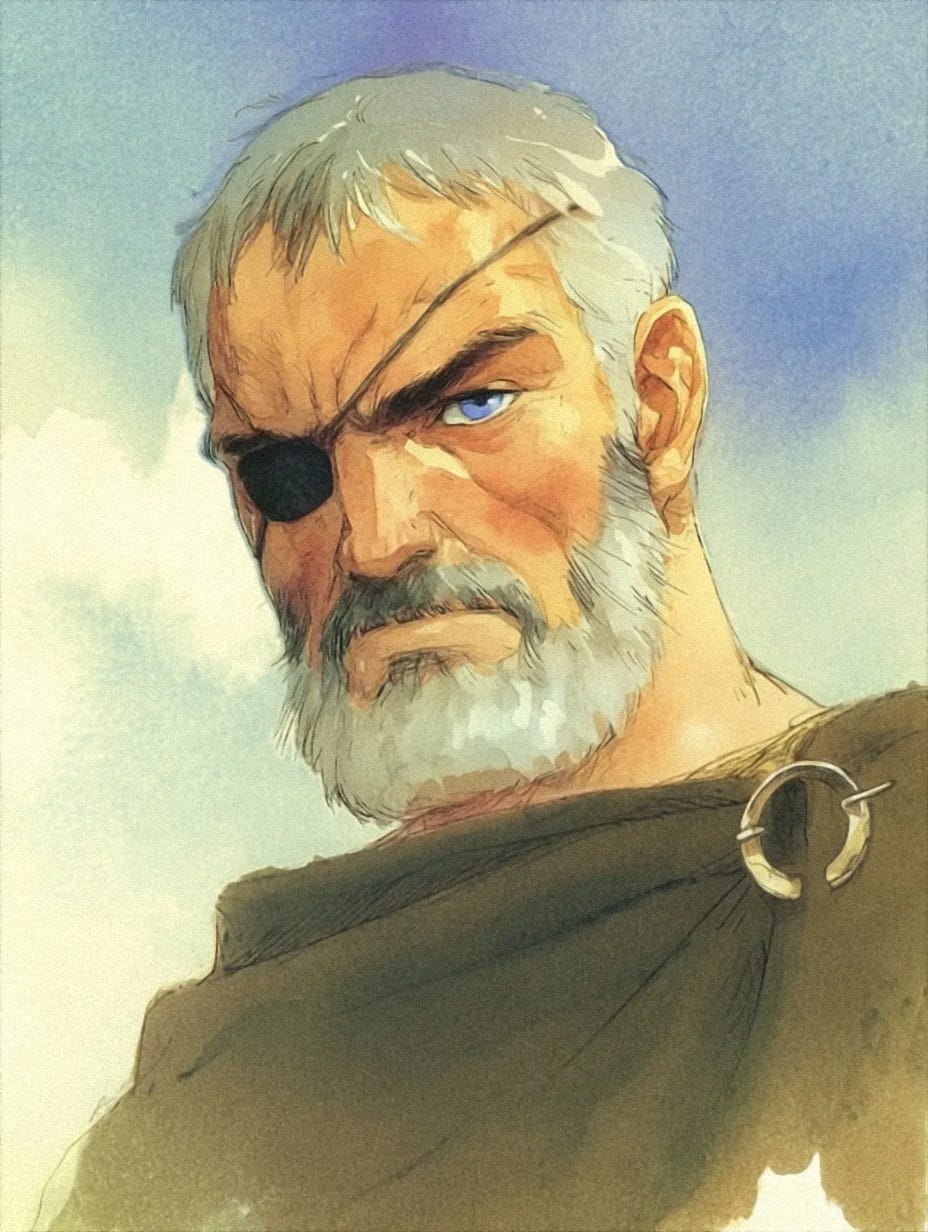

“I saw the making of the One-Eyed King.”

Urien's voice was low, steady, but there was iron beneath it—something that had long since cooled, but never been quenched.

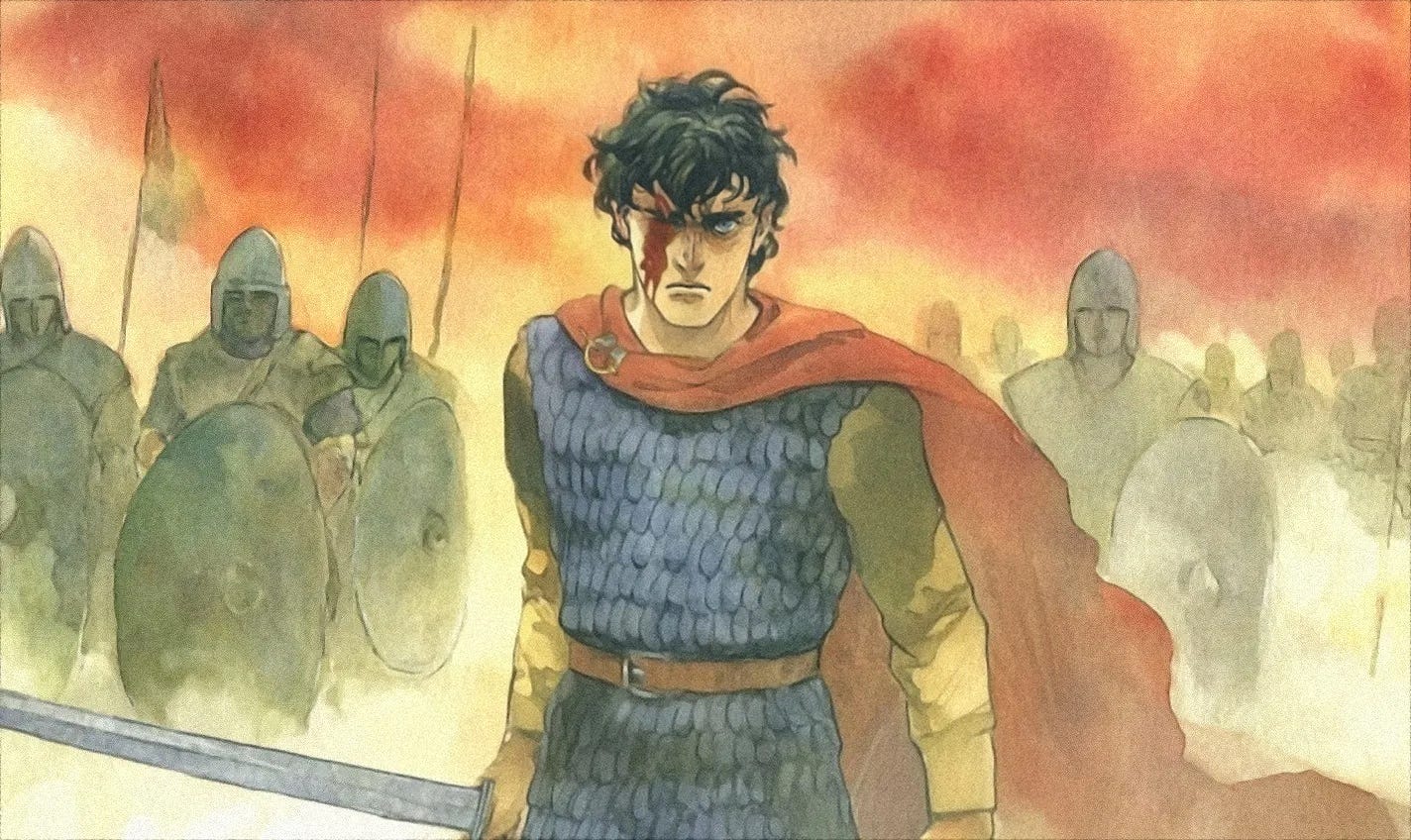

“We were seventeen—barely bearded, thumping lance on shield, shouting boasts of glory not yet earned. We were young and foolish and full of fire. I wore your grandfather’s lorica that day. Golden Roman scale, shining like the summer sun, though patched here and there with northern iron. It glimmered even in the sickly sun, as if defying the gloom.”

He paused, eyes far away.

“We rode to Camlann beneath Arthwys himself—the old High King, the Bear, our kin and war-lord. A banner of red and gold streaming over us, snapping in the cold wind. At his right rode Llenneac, shining in silver scale said to be Coel’s own, unblemished even in it’s old age. Two scions of Coel. Brothers.”

Urien pulled away a loose board from the battlements where the old roman walls were repaired with wood, frowning.

“I remember Guallauc well that morning—spirited, sharp-witted, laughing loud and long at my poor horsemanship. Even then he was broad of shoulder, dark-eyed, and already strong as a bull. He wore a silver helm, and from it flew a crest of black feathers, defiant, proud. A dark echo of his father’s white crest beside him, like night marching with day.”

“But then came the fog.”

Urien’s voice thinned, a long silence trailing his words.

“It rolled down from the hills like a living thing—grey and thick and foul-smelling, choking out the sun until the earth was drowned in shadow. The banners disappeared. The shouting dulled to moans. And then the killing began.”

“The battle-din was a nightmare. Spear on shield, iron grinding, horses and men shrieking… at a point we all sound the same. Smoke rose from burning huts near Caer Camlann, and arrows fell like dead leaves. We struck their flank near the riverbank—our cavalry thundered across the shallow river crossing crashing into the host attacking Ceidio’s fortress. Hooves churned frost, blood, and shattered bone. I killed my first man there—some brute from Alt Clut, swinging a chipped axe and howling curses. He came at me like death unshackled. His axe took my horses legs, my spear gone and shield under the dead horse. I leapt to my feet, sword flashing from scabbard as the rest of our Teulu rode through their ranks. The man screamed his kings name as the axe glanced across my lorica and I plunged my sword into his throat.”

He looked down at his hand, as though remembering the weight of that first kill.

“But Llenneac... Llenneac fell like a hero of old. Not cowering, not cornered—but charging, sword high, toward the riverbank where Arthwys stood against Medraut of Gododdin. Llenneac carved a path through man after man, silver scale slick with blood, his white crest torn and trailing like a comet’s tail. He fought on, blade flashing in arcs of fire, and each stroke felled a foe. Ten men? Twenty? But still he pressed on.”

Urien’s eyes burned now with something older than grief—reverence, perhaps.

“He was nearly there. Medraut had driven Arthwys into the riverbend, where the wind cut like knives and the sand was slick with blood. The High King stood beneath the tattered red-gold banner, Caledfwlch broken in hand, the last of his Teulu with him. And Llenneac, his brother, would not let him die alone.”

“But fate cares not, and cold the wind blows.”

Urien’s voice grew cold.

“A nameless man met him as he thundered towards Medraut. No armor. Just rage and battle-lust. I saw the blue-green tattoos on his chest and square shield. The Pict thrust a crude spear—ash-hafted, the head still covered in forge-scale—and struck Llenneac beneath the arm, where even Coel’s silver scale gave no shelter. And that was the end. The hero fell not to a champion, but to some wretch from Pictland.”

“Guallauc saw it—no more than a dozen strides away. He had lost his horse and his helm, waded through the gore teeth bared like a beast. He saw his father fall—collapse without a cry, face-first into the red mud, sword lost beneath him. And something in him shattered.”

Urien’s hand tightened on the edge of the battlements.

“He screamed then—not a name, not a curse—just rage, raw and wordless. And after that, I think, Guallauc forgot who he was. Or perhaps he remembered only the part that would survive.”

He looked up, meeting Owain’s eyes.

“And on the riverbank, Arthwys bled. Medraut’s blade was red, and the golden banner sagged in the dying wind. The High King fell with three of his shield-men about him. I watched Medraut fall to his knees bleeding beside our High-King with what was left of Coel’s sword buried in his chest through maille, tunic, and heart. Medraut took his last breath on that riverbank.”

He looked at Owain.

“Two brothers, two kings—fallen within the same hour. The sisters of Aballava could not save him. The old High-King dead, carried to his final raid on a ship to the otherworld. After that the flame that bound the Coeling scattered into sparks. Some went cold. Others burned wild.”

He stepped closer to Owain, voice barely more than a whisper.

“That was the hour Guallauc lost his eye. No one speaks of it—not even he—but I saw him pull the broken shaft from his face, blood streaming down his cheek. He fought on blind on that side, cleaving men like harvesting grain. When the smoke cleared, he stood with Eliffer’s gosgordd, the right side of his face was blackened, the eye gone. But his sword hand never wavered.”

Urien’s jaw clenched.

“He left that field a man, aye—but not the one he might’ve been. The Guallauc we knew was buried in that mire beside Llenneac. What rose was the One-Eyed King.”

Owain stood still now, the anger cooling from his face.

“That changed him,” Urien said. “Changed all of us. But Guallauc... he became iron, hammered and warped. While I turned to alliances and fortresses”

Owain coughing mockingly.

“Aye boy I raided too, how else to make it through those years? Guallauc was steeped in blood. When the sun failed us and the fields yielded rot—when the summer itself gave no warmth—he endured. He did more than that. He fought. Patrolling the southern border relentlessly. No Saeson warband would enter Elmet. Endless raiding, taking cattle from Lindon, Gododdin, Alt Clut, anyone he could… and it kept our enemies weak.”

“There was no peace after Camlann,” Urien continued. “Only vengeance. And much of it was among our own. Eliffer of Ebrauc—slain by his own brother, Ceidio. Coeling slaying Coeling, crown for crown. Then Guenddoleu, Ceidio’s son, took up his father’s name in fire. But not for feud. He reached to me.”

He looked at Owain.

“I allied with Guenddoleu. Not just for Rheged—but for kinship, for some thread of order. We tried to bind the wounds. Petitioned Eliffer’s sons for peace. Peredur and Gwrgi would have none of it. They waited, bided their time, and attacked at Arfderydd. You saw first hand the weight of a blood feud after you slayed Ida’s whelp. Guallauc and I settled with the twin kings, and again they bided their time and waited. They betrayed us again. Their brother, Madog fled to Gododdin, leading Morcant’s armies as his Pen Teulu, And so the bloodletting continued.”

A long silence.

“You watched as Guallauc broke them at Catraeth. Leading his riders into their camp and almost ending the battle before it started. I saw him take three heads in one pass, sword shining in hand like his father’s. He came to me then, and looked at me with that single fierce eye. Told me what was to come, how Eliffer’s line would end. When the day’s killing was done, he marched on Caer Ebrauc, and drove Gwgon from the fortress, carrying Peredur’s head taunting the boy.”

“And yet,” Owain said, slowly, “you call this man friend?”

“I call him shield,” Urien said. “He is no gentle hand, but his wrath has kept the men of Lindon wary, they dare not cross into Elmet. Ælla is terrified of him, even though he gives us both tribute, and Ida’s ilk think twice before coming south even to steal a few cattle. Not for fear of me, but of him. He is the spear of the Coeling, and every man, from Pictland to Cerniu knows his name.”

Urien stepped forward, placing a firm hand on his son’s shoulder.

“We are the blood of Coel, Owain. Scattered, cracked, but still bound. You will meet Guallauc again. You will ride beside him, or face him. But if you are wise, you will do the first. Yield pride where you must, and hold the line when it matters. He has spilled the blood of kin before. But only when kin rose against him.”

He looked his son in the eyes.

“Let us not give him cause again.”

I know my normal fare has been scarce of late, as I am working hard on wrapping up the Illustrated Guide so I can get it released before the end of the year. I have completed 55 feature illustrations, with around 20 more to go, along with a section of assorted illustrations at the end of the book that will only be captioned. I will do this for figures that have less that can be said about them, as well as concepts that are self-explanatory, and for things I want to include just because I like them.

The concept for this story has been plaguing my dreams for a month or so. I have tried my hand at fiction before here, but I do not feel that it’s a strong point of mine. I am not a great writer at all in my opinion, but I do get the urge to paint something with words once and a while. Looking at Guallauc’s legacy in the songs of the Bards, though less than say Urien, still gives one a heavy impression of the man. A violent and dangerous raider of a king, an enemy of everyone but Urien it seems. In the late 6th century the Coel’s Kindom of Northern Britain became extremely fractured, and it seems that even amongst those still holding true to their kin were still wary of one another, and it seems those ties were severed as soon as Urien was assassinated. Guallauc did ultimately make war on Urien’s sons, and I get the impression that his motivations probably lie in a grand opportunity to make Elmet the most powerful kingdom of the north, or more nobly (kind of) resentment of Urien’s great influence, entitlement (being that the only Coeling left that was around his age were Pabo’s children), and even more speculatively a sense of duty to maintain his family’s claims, with him the only one to be able to ensure it. We of course can’t project our analysis of personal feelings into the past, but I think it still makes for a fun read.