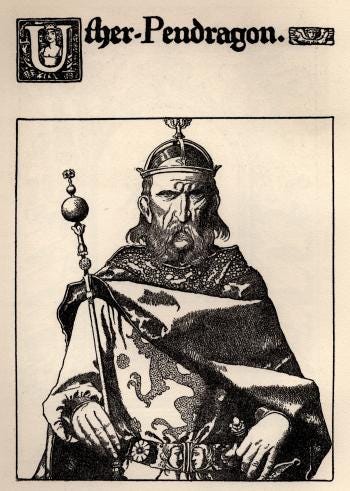

Arthgallo, Arthwys ap Mar, and Arthur

An interesting excerpt from Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae

This is going to be a small expansion upon the last part of my article in Issue 7 of Raw Egg Nationalist’s wonderful Man’s World Issue 7. In that article I put the spotlight on three figures I think play some part in Arthur’s creation. One of these was Arthwys ap Mar. I will eventually do a longer piece focusing exclusively on him, and what we can glean about him, but for now I want to show how some of these medieval chronicles can accidentally shift history trying to make a coherent story.

Geoffrey’s History

Within Geoffrey of Monmouth we get a few stories that would seem to recount the the exploits of a few Kings of Northern Britain, I’ll start with his account of Morvidus (Morydd). Geoffrey tells us the following first.

He would have been a prince of extraordinary worth, had he not been addicted to immoderate cruelty, so far that in his anger he spared nobody, if any weapon were at hand. He was of a graceful aspect, extremely liberal, and of such vast strength as not to have his match in the whole kingdom.

He then recounts Morvidus’ defense against an army from what is now Boulogne, and his subsequent death to a monster from the Irish sea.

CHAP. XV.—Morvidus, a most cruel tyrant, after the conquest of the king of the Morini, is devoured by a monster.

In his time a certain king of the Morini arrived with a great force in Northumberland, and began to destroy the country. But Morvidus, with all the strength of the kingdom, marched out against him, and fought him. In this battle he alone did more than the greatest part of his army, and after the victory, suffered none of the enemy to escape alive. For he commanded them to be brought to him one after the other, that he might satisfy his cruelty in seeing them killed; and when he grew tired of this, he gave orders that they should be flayed alive and burned. During these and other monstrous acts of cruelty, an accident happened which put a period to his wickedness. There came from the coasts of the Irish Sea, a most cruel monster, that was continually devouring the people on the sea-coasts. As soon as he heard of it, he ventured to go and encounter it alone; when he had in vain spent all his darts upon it, the monster rushed upon him, and with open jaws swallowed him up like a small fish.

After his death we get an account of his eldest son Gorbanian (Gorviniaw), a righteous and powerful king, who led his people into a golden age.

CHAP. XVI.—Gorbonian, a most just king of the Britons.

He had five sons, whereof the eldest, Gorbonian, ascended the throne. There was not in his time a greater lover of justice and equity, or a more careful ruler of the people. The performance of due worship to the gods, and doing justice to the common people, were his continual employments. Through all the cities of Britain, he repaired the temples of the gods, and built many new ones. In all his days, the island abounded with riches, more than all the neighbouring countries. For he gave great encouragement to husbandmen in their tillage, by protecting them against any injury or oppression of their lords; and the soldiers he amply rewarded with money, so that no one had occasion to do wrong to another. Amidst these and many other acts of his innate goodness, he paid the debt of nature, and was buried at Trinovantum.

After Gorbanian’s idyllic rule his brother Arthgallo (Archgallo, Arthal), takes the crown and leads the realm into darkness until being deposed by his brother Elidure (Elidyr), and is eventually restored to kingship and Arthgallo rules well from then on.

CHAP. XVII.—Arthgallo is deposed by the Britons, and is succeeded by Elidure, who restores him again his kingdom.

After him Arthgallo, his brother, was dignified with the crown, and in all his actions he was the very reverse of his brother. He everywhere endeavoured to depress the nobility, and advance the baser sort of the people. He plundered the rich, and by those means amassed vast treasures. But the nobility, disdaining to bear his tyranny any longer, made an insurrection against him, and deposed him; and then advanced Elidure, his brother, who was afterwards surnamed the Pious, on account of his commiseration to Arthgallo in distress. For after five years' possession of the kingdom, as he happened to be hunting in the wood Calaterium, he met his brother that had been deposed. For he had travelled over several kingdoms, to desire assistance for the recovery of his lost dominions, but had procured none. And being no longer able to bear the poverty to which he was reduced, he returned back to Britain, attended only by ten men, with a design to repair to those who had been formerly his friends. It was at this time, as he was passing through the wood, his brother Elidure, who little expected it, got sight of him, and forgetting all injuries, ran to him, and affectionately embraced him. Now as he had long lamented his brother's affliction, he carried him with him to the city Alclud, where he hid him in his bed-chamber. After this, he feigned himself sick, and sent messengers over the whole kingdom that they should come to visit him. Accordingly, when they were all met together at the city where he lay, he gave orders that they should come into his chamber one by one, softly, and without noise: his pretence for which was, that their talk would be a disturbance to his head, should they all crowd in together. Thus, in obedience to his commands, and without the least suspicion of any design, they entered his house one after another. But Elidure had given charge to his servants, who were set ready for the purpose, to take each of them as they entered, and cut off their heads, unless they would again submit themselves to Arthgallo his brother. Thus did he with every one of them apart, and compelled them, through fear, to be reconciled to Arthgallo. At last the agreement being ratified, Elidure conducted Arthgallo to York, where he took the crown from his own head, and put it on that of his brother. From this act of extraordinary affection to his brother, he obtained the surname of Pious. Arthgallo after this reigned ten years, and made amends for his former maladministration, by pursuing measures of an entirely opposite tendency, in depressing the baser sort, and advancing men of good birth; ion suffering every one to enjoy his own, and exercising strict justice towards all men. At last sickness seizing him, he died, and was buried in the city Kaerleir.

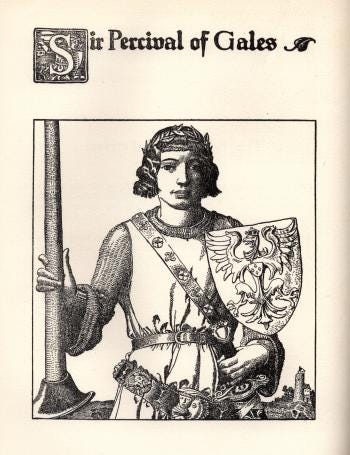

Geoffrey further recounts Elidure’s rule and deposition by his youngest brothers Peredure (Peredur) and Vingenius (Ingenius, Owain), and Elidure’s subsequent restoration.

CHAP. XVIII.—Elidure is imprisoned by Peredure, after whose death he is a third time advanced to the throne. Then Elidure was again advanced to the throne, and restored to his former dignity. But while in his government he followed the example of his eldest brother Gorbonian, in performing all acts of grace; his two remaining brothers, Vigenius and Peredure, raised an army, and made war against him, in which they proved victorious; so that they took him prisoner, and shut him up in the tower at Trinovantum, where they placed a guard over him. Then they divided the kingdom betwixt them; that part which is from the river Humber westward falling to Vigenius's share, and the remainder with all Albania to Peredure's. After seven years Vigenius died, and so the whole kingdom came to Peredure, who from that time governed the people with generosity and mildness, so that he even excelled his older brothers who had preceded him, nor was any mention now made of Elidure. But irresistible fate at last removed him suddenly, and so made way for Elidure's release from prison, and advancement to the throne the third time; who finished the course of his life in just and virtuous actions, and after death left an example of piety to his successors.

The Genealogies

While the stories themselves are interesting, I believe that they are general copy and paste kind of templates of dynastic squabbles. The real interest here is not the exploits of these men, but that they all seem to be misremembered versions of some of the Coelings, specifically the roughly four generations post Rome, at the beginning of the Brythonic Heroic Age as I call it.

Morvidus, and each of his ‘sons’ have counterparts in the genealogies of the Coelings. The interesting thing here is that things don’t like up exactly, and it leads me to the conclusions that Geoffrey was working from either a fragmentary northern regnal list that he didn’t have proper dating for, or a lost northern chronicle that doesn’t necessarily tell of the relations between this figures, but instead of their inner squabbles.

So here we can see that it seems that Geoffrey’s version just assumes that all of these figures subsequent to Morvidus are his sons, whereas the truth seems like it may be more complicated.

It is likely that the succession he follows is correct, and that Mar’s uncle Garbanian took the throne after him until Arthwys came of age, Arthwys was then succeeded (or deposed, echoes of the civil strife common in Arthur’s late reign in most stories) by Ellifer, who is in turn deposed by his sons, who are eventually defeated by the Angles.

Arthur, by another name

It is interesting to see these parallels here, and interestingly enough Geoffrey may have been recording more about King Arthur (as Arthwys is likely one of the many components of the later composite Arthur) than he actually intended to, by including the story of Arthgallo. In an effort to fill in his narrative gaps, Geoffrey took this undated chronicle and made it fit where he thought it should, and if Arthgallo ap Morvidus (Arthal ap Morydd) and Arthwys ap Mar are indeed the same figure (they most certainly are) Geoffrey shifted their story by around 800 years!

I close here with part of a poem, written by William Wordworth 1300 years after Arthwys lived, inspired by the story of brotherly love shown by Elidure to his brother Arthgallo (here called Artegal)

The people answered with a loud acclaim: Yet more;-heart-smitten by the heroic deed, The reinstated Artegal became Earth's noblest penitent; from bondage freed Of vice-thenceforth unable to subvert Or shake his high desert. Long did he reign; and, when he died, the tear Of universal grief bedewed his honoured bier.