End of the year compilation

Threads from twitter that haven't been expanded into full articles.

It has been a busy year, and much work of mine from twitter has not made it’s way here. Below you will find threads that really are so concise as to not merit full articles, as well as some threads that are planned to eventually be expanded. My threads on Taliesin and Yr Afallenau are both absent, as I am currently working on realizing the final version of them for Substack, and hope to publish those by January at the latest. My book “The Brythonic Heroic Age: The Coeling” is very close to completion after many unfortunate delays, and I have released an Arthurian themed colouring book, which can be found on amazon here, and is currently on sale for Christmas! (make sure to change your region appropriately or else it will show as unavailable.)

Below you will find almost 15000 words worth of content those who don’t follow me on twitter may not have seen. You will find an index below to help navigate through, unless you plan on just reading straight down the page. These are in no particular order, so read one, two, all or none, whatever strikes your fancy.

1. St. Patrick

2. The many sons of Mar ap Ceneu, and their few kingdoms.

3. Owain ap Eliffer? The true name of Gwrgi of Ebrauc

6. Arthur of Gwent: Athrwys ap Meurig

8. Arthur’s European Campaign and Riothamus

9. Geraint of Dumnonia, and the Battle of Llongborth.

12. The Alleluia Victory of Germanus

13. Pabo Post Prydain, The Pillar of Britain, and the questionable chronology behind him.

14. Yrfrai

16. Cadrod Calchfynydd and Amhar ap Arthur, an odd connection.

17. Gartnait, a Pictish form of Arthur?

18. St. Derfel The warrior-turned-monk who survived Camlann.

19. Taliesin's poem Kat Godeu, and some possible historicity.

20. The theory of an early Battle of Catraeth and a nephew of Arthur's, Guallauc ap Llenneac.

21. The Deaths of Peredur and Owain of Ebrauc

22. Tristan ap Tallwch, or Drest son of Talorc?

23. Pa Gur: Arthur’s roster of heroes

24. Dyrnwyn

26. Faces of Arthur pt. 1: Many potential figures, many potential problems.

27. King Arthur in Film Part 1: King Arthur (2004)

28. King Arthur in Media Pt. 2: Emergency Edition: The Winter King, Episode 1

St. Patrick

From St. Patrick's letter to Coroticus' Warband "Soldiers whom I no longer call my fellow citizens, or citizens of the Roman saints, but fellow citizens of the devils, in consequence of their evil deeds; who live in death, after the hostile rite of the barbarians"

"associates of the Scots and Apostate Picts; desirous of glutting themselves with the blood of innocent Christians, multitudes of whom I have begotten in God and confirmed in Christ." This Coroticus that St. Patrick was writing to is none other than Ceredig Wledig of Alt Clut!

This is one of the things that is helpful for dating St. Patrick himself, as Ceredig can be dated by working backwards from more sure dates of his descendants. If Coroticus is Ceredig it places St. Patrick in the late 4th century and early 5th century.

Also of note, that Ceredig seems to have ruled after the Roman exit from Britain, and the Saint's words here imply that many of the British still viewed themselves as Roman Citizens, although they were no longer part of the empire proper.

The many sons of Mar ap Ceneu, and their few kingdoms.

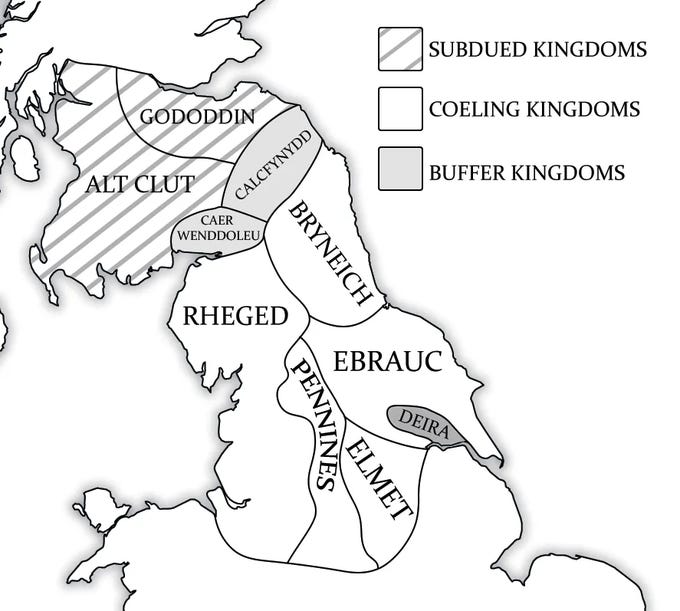

Mar is generally listed as having four sons, Arthuis, Llenneac, Einion and Morydd, (and sometimes a fifth, Ceredic) but only Arthuis and Llenneac seem to have inherited substantial territory. I have some theories.

Upon his father Ceneu's abdication Mar became the first King of Ebrauc, while his brother Gwrwst became the first King of Rheged. Their younger brother Pabo was likely not yet of age, and as such his later territory was controlled by Ebrauc at the time.

Mar dies an untimely death around the year 485, likely to Irish raiders, possibly even to Fergus Mor, an early King of Dál Riata. Mar's eldest sons Arthuis and Llenneac were in their early teens at the time.

Mar's uncle Garbanian, the King of Bryneich steps in as regent. This does not seem to have been a willing arrangement for long, and eventually once Arthuis and Llenneac are of age they make war on their Great-Uncle to take back their father's kingdom.

I have recently found something new while working on my book. I have mentioned how I have a theory that there is a now lost regnal list of the kings of Brythonic Ebrauc (York), discussion of which can be found here in this article.

With Garbanian subdued, the brothers split Ebrauc into Elmet (Llennaec) Ebrauc (Arthuis) and The Pennines (Pabo their young Uncle). His brothers Morydd, and Einion are unaccounted for however. Were these younger brothers left out, or can they possibly be accounted for?

Both Einion and Morydd supposedly had descendants. Einion was the father of Rhun Ryfeddfawr (the Wealthy), who fathered a daughter, Perwyr who became the wife of Maelgwyn Gwynedd. Rhun's epithet 'The Wealthy' would indicate some status, as well as his daughter’s marriage.

Assigning a kingdom to him is difficult though. Einion is sometimes assumed to be a king of Ebrauc, stemming from older scholarship that used a later genealogy listing Ellifer of Ebrauc as a son of Einion, when the earliest references list Ellifer instead as a son of Arthuis.

Morydd has a son Madog, who is in turn the father of Myrddin Wyllt, the historical inspiration for Merlin. Myrddin was an advisor to a grandson of Arthuis, Gwenddoleu ap Ceidio, the King of a small kingdom known as Caer Wenddoleu.

So did these two younger brothers not inherit, or is there an explanation? There just may be. I have written at length about the buffer states that Arthuis seems to have set up for his children, however, could it be that these were instead set up for his younger brothers?

You can find more explanation behind my theory of Arthuis' buffer states if you would like to read below. While I think this buffer state theory is likely true, I think there may be some more nuance to it that I have yet to touch on.

Morydd's grandson is associated heavily with one of these border kingdoms, Caer Wenddoleu, and if Morydd is actually the Medraut mentioned in the Annales Cambriae's entry on Camlann, the circumstantial evidence seems to lead to Morydd being the first king of this territory.

The battle of Camlann likely was a cattle raid by the Gododdin and Alt Clut targeting Rheged, that was stopped at the fortress of Camboglanna by a combined force of Coelings, including a young Urien of Rheged. Camboglanna is on the border between Caer Wenddoleu and Rheged.

If Morydd is the Medraut of Camlann it further associates him with this area, and strengthens the possibility that Morydd was the first king of the territory that became Caer Wenddoleu.

I think it's possible even that Arthuis' son Ceidio may have been fostered with Morydd, leading to power being transferred to Ceidio upon Morydd's death instead of his son Madog, who still would have been fairly young.

This would leave Calchfynydd to Einion initially, then passing hands to Arthuis' son Cynfelyn, passing over Einion's son Rhun. This one has less evidence than the case for Morydd, however, it's still a possiblity, and could even explain Rhun's 'Wealth' as a privileged sub-prince.

As always, this is conjecture, and is open to interpretation, but unfortunately for a period with so few records these tenuous reconstructions are all we have.

Owain ap Eliffer? The true name of Gwrgi of Ebrauc

Gwrgi, when mentioned, is usually paired with his brother Peredur. Gwrgi itself is an unusual name, and only appears in a few places, often with fanciful associations. Let's take a look at some of these other Gwrgis and at a hint at Gwrgi ap Ellifer's true name.

One of the most famous Gwrgis is Gwrgi Garwlwyd (meaning roughy Man-Dog Rough-Grey) who figures in the fragmentary poem Pa Gur as an antagonistic figure at the battle of Tryfrwyd (Tribruit) defeated by Bedwyr. The same Gwrgi features in the triads.

In the triads he is known as one of the "Three Disgraceful Saxon Traitors" This triad is a mix of believable elements, and those that strain credulity. Edlfled is a hard one to pin down, and may be a rendering of Æthelfrith or Æthelflæd, or possibly just a 'Saxon' sounding name.

Gwrgi also here eats two young people a day. This Gwrgi seems to be the stuff of legend, though could be a memory of a notorious Brythonic raider, perhaps living under the protection of an early king of Deira?

There are also mentions of men named Gwrgi, one who helps hunt the boar Twrch Trwyth and another who is a vassal of Pryderi. Not much can be drawn on either of these to come to any real conclusions.

Gwrgi ap Ellifer then stands alone as the one solid historical mention of a Gwrgi, but what if that wasn't actually his name?

Within Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae there is a string of kings that match very closely to the late 5th and 6th century kings of Ebrauc. Within that narrative line many names seem familiar.

Among them you will find Mar (Morvidus) Garbanian (Gorbanianus) Arthuis (Archgallo) Ellifer (Elidurus) and finally Peredur and his brother... Owain? (Peredurus and Ingenius)

The links here are striking, and it is quite obvious that Geoffrey was drawing his history here from a lost northern chronicle or king list. There are only two major discrepancies when it comes to matching these legendary kings from Geoffrey to the northern pedigrees.

The first is Gorbanianus, or Garbanian, who I have written at length about in numerous articles, one of which you can find here below. Garbanian's intrusion seems to be a case of failed usurpation or possibly a role of regent for a young Arthwys.

Arthgallo, Arthwys ap Mar, and Arthur

An interesting excerpt from Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae

The second discrepancy comes to Peredurus and Ignenius. Ingenius is a form of the name Eugenius, which is commonly rendered in Brythonic as Ewein, or Owain. Could this be a memory of Gwrgi's original name?

Might Gwrgi have been an epithet for Peredur's twin whose real name was Owain? Owain was a relatively popular name, with Owain ap Urien being one of the most famous bearers from this period. I would propose that Gwrgi was a nickname given to an Owain ap Ellifer.

After his and Peredur's death Owain ap Urien's exploits may have overshadowed Gwrgi, and eventually a man who may have been called Owain with a nickname of Gwrgi just becomes Gwrgi in any place he appears, in order to distinguish him from the more famous Owain ap Urien?

The wife of Coel

It is always interesting to come across something that you've probably seen before but didn't necessarily take note of, and a prime instance is a Triad that I have since overlooked. This time involving Old King Coel, and particularly his Wife.

"Stratweul daughter of Cadfan ap Cynan ab Eudaf ap Caradog ap Bran ap Llyr Llediaith; and this Stratweul was wife of Coel Godebog. She was the mother of Cenau ap Coel and the mother of Difyr. Others say that she was called Seradwen daughter of Cynan ab Eudaf ap Caradog."

While Stratweul or Ystradwal as she is sometimes called like likely a dubious name (it means Street-Wall, likely a reference to Coel's lordship over Hadrian's Wall) Seradwen is not, and may represent a memory of her actual name.

Not only do we get her name though, we get her parentage, making her a great-granddaughter or grandaugter of Eudaf Hen. This is an especially helpful tidbit to have when it comes to putting a firmer date on Coel Hen, who people have tried to place as far back as 250ad!

The key here is Eudaf's daughter Elen, the wife of Magnus Maximus, placing her birth somewhere around 350-360, thus giving us a starting point for the next generation, giving Eudaf's granddaughter or great-granddaughter Seradwen a range between 380-410 roughly.

This also gives us a rough feeling for Coel's dates as well, generally no earlier than 380 would be acceptable, and this works out extremely well with dating Coel's descendants who have been notoriously hard to pin down by most 'Experts'

We are also given another little tidbit here, and that is the children mentioned, we see the familiar Ceneu, the grandfather of the Northern Arthur, Arthwys ap Mar, but the other mentioned is relatively unknown and unattested, Difyr.

This could reinforce the notion that Coel's other son Garbanian was not born with the name he is known by in most sources, and instead was born Difyr. Nothing extremely solid here, but interesting nonetheless.

Father’s Day Thread

It's Father's Day today, why don't we talk about the sons of Arthwys ap Mar, one of the first contributors to the 'King Arthur' legend.

The Legendary Arthur is not known for being a fantastic father, with one of the earliest stories attributed to him being the location of the grave of his son Amr, or Amhar, who Arthur supposedly killed. This later gets transferred to Mordred as a Nephew/Son.

There is however little evidence of conflict between Arthwys and his sons, Eliffer, Ceidio, and Cynfelyn, the three of which headed mighty kingdoms in Northern Britain during the 6th century. A third son Greidal is less attested and requires some logic to realize.

Eliffer Gosgorddfawr, or Eliffer of the Great Host (or army) Ruled his father's kingdom of Ebrauc in basically it's entirety, unsplit as was normal tradition amongst scions of Brythonic kingdoms. His epithet echoes the mighty warband his father must have commanded.

Eliffer ruled from his fathers death in 537 for around ten years, likely dying in battle against Ida of Bernicia in 447, after which Ida established the Anglish kingdom of Berncia, and set in motion events that would change the fabric of Northern Britain.

Eliffer's own sons, Peredur and Gwrgi (Gwrgi's birth name was likely Owain) extremely young at their fathers death eventually inherited their father's throne, ruling until their deaths, likely in a civil war against their cousin Urien of Rheged.

Ceidio, who ruled a buffer state between Alt Clut and the kingdoms south of Hadrian's wall, inherited a kingdom that is not generally thought to have been part of his father's realm. This curious bit actually provides evidence for his father's far reaching power.

While other kingdoms were shrinking and fracturing, the territory controlled by Arthwys was increasing. Ceidio is directly known mostly from his own son, Gwenddoleu, who was called 'a powerful prince' and is remembered as owning one of The Thirteen Treasures of Britain.

His treasure was a Golden Gwyddbwyll board, with silver pieces. Once the pieces were set the game would then play itself. Gwenddoleu was also the lord of the historical Merlin, Myrddin Wyllt, who went mad upon Gwenddoleu's death in battle against his cousins Peredur and Owain.

Cynfelyn is the progenitor of the kingdom of Calchfynydd, often thought to be located in the Chilterns, it is more likely that it was in Kelso, in the borders. Another buffer state, this time defending family territory from the Gododdin, as well as Alt Clut.

His son Cynwyd, marries a woman named Peren ferch Greidal. Peren's father Greidal is given as Greidal ap Arthwys ap Garmon. No Arthwys ap Garmon is found amongst other genealogies, however that does lead us to Arthwy's likely fourth son.

Greidal is likely also a son of Arthwys ap Mar, with Arthwys' father Mar being replaced by his great uncle Garbanion, or Garmon, who ruled Ebrauc for a short time before Arthwys took the throne. For the sake of brevity you can read more on this here.

If Greidal ruled a territory we have little evidence of where it was, it is possible that he died before gaining any sort of land or kingdom, only living old enough to father Peren.

While the later legendary Arthur may have been a poor father, Arthwys himself doesn't seem to be a reflection of this at all, instead seeming as a powerful man who set up his children to prosper as best he could before his death at Camlann.

Arthur of Gwent: Athrwys ap Meurig

Much has been made of Athrwys ap Meurig, the grandson of the famous Tewdrig, who the victor of The Battle of Pont y Saeson. Tewdrig had abdicted in favor of his son Meurig, but came out of his monastic retirement to lead his warriors one last time.

Tewdrig died of wounds shortly after the battle. The dating of this battle, and the kings of Gwent/Glywysing are of uncertain datings, and many have worked to shift them into the period that they prefer to account for Tewdrig's grandson Athrwys to be 'THE ARTHUR'.

Far flung dates have been proposed placing Athrwys in the late 5th century, as well as other attempts making him extant throughout the 6th century. Some have combined their reckoning with a misconstrued dating of the Annales Cambriae, claiming that the dates are off by 35 years.

This comes from the suggestion that the Agitius mentioned in the 'Groans of the Britons' is actually Aegidius, the ruler of the Kingdom of Soissons, who has been misdated to the late 470s. Aegidius ruled earlier, actually ruled earlier than this proposed dating.

The letter in all likelihood was send to the famous Aetius, magister militum of Rome in the 440s. This misconstrued dating shifts events 35 years forward, and combined with some creative liberties for Athrwys' chronology shifts things just right where the 'scholars' want them.

The Annals themselves are not necessarily dated by this suggestion though, and are instead dated by an entry referencing Pope Leo I adjusting the date of Easter, leaving the Aegidius/ Aetius argument moot.

We are lucky enough that we have a fairly solid date on a descendant of Athrwys, Ffernfael ab Idwal, his great-grandson. Ffernfael died in 775 according to the annals, which in this case is unlikely to be wrong, as it is less than 50 years out from when they were first solidified

Making the assumption that Ffernfael lived to 100, and that he was sired by a line of geriatric fathers (extremely unlikely) you can get a date for Athrwys of 525. Close to the likely period the historical Arthur existed, but still almost two generations too late.

even with the 35 year shift forward this puts the Arthurian events of the annals into this prospective chronology, but it also shifts his birth out another 35 years, as then Ffernfael would have been born in 710, putting Athrwys' birth around 560, further desyncing things.

With the much more likely average generation of 27 years and accepting the date of the Annals for Ffernfael's death gives Athrwys a birth of 614, a much more likely date, but far out from when any reckoning of Badon and Camlann can be placed.

Athrwys still may have played his part in the later composite Arthur however. He became king of Ergyng around 645, a place long associated with Arthur, and situated close to Caerleon, a place heavily associated with Arthur.

Memories of Athrwys blended with others may be the explanation for the later southern affectations of the legendary Arthur.

What’s in a Name

One common thing that pops up when it comes to Arthuriana is the modern insistence that 'Artorius' is the correct rendering of Arthur's name. This is a notion created by scholars to try and explain an etymology of the name. This is likely incorrect though.

Arthur is never rendered as Artorius in any examples prior to modernity. Latinisations range from Arturus, Arthurus, and Arthurius (in Irish texts), and is generally rendered in Brythonic as just plain Arthur. Arthwyr is seldom used but is attested.

Arthwys is likely a related name, and as my friend @lmrwanda has pointed out in an article is in all likelihood an older rendering of Arthur, which is Arthwys with the final s rhotacised. Artognou, as seen on the famous stone from Tintagel is probably a dialectal variant.

I have pointed out recently as well that Gartnait was likely also another dialectal variant of Arthur, this time coming from the Picts. Artorius as tempting as it is to assign as the etymology of Arthur upon close inspect of alternatives just doesn't hold as much weight.

That doesn't mean it isn't a possibility, it just with all things considered ranks significantly lower than the other Celtic origins of the name. Arthwys and by proxy Arthur probably derive from a Proto-Celtic name meaning 'Bear Hunter'. Very Indo-European!

Arthur’s European Campaign and Riothamus

One of the pieces of the Arthurian puzzle that many stumble on, and will often skew and stretch their candidate to fit, is Arthur's European campaign. While I do not feel compelled to stretch my candidate Arthwys to fit it, I do think there is an explanation.

I have discussed the idea of a 'composite' Arthur before, and I do believe that Geoffrey's Arthur is just that, a composite, I have explained before, this doesn't preclude my candidate Arthwys ap Mar from being the start of it, but many figures contribute to the Galfridian Arthur

One of the common ideas, which does carry some merit, is the wars of Magnus Maximus on the continent, ultimately leading to his Magister equitum Andragathius capturing and killing Gratian, leading to Magnus Maximus becoming emperor.

Magnus is known in Brythonic tradition as Macsen Wledig, and is a well regarded figure within legend. Many have suggested that these campaigns were grafted on to Arthur at a later period, and while this is possible, I think there is a more likely solution.

Riothamus stands as an interesting figure here, being well attested in history, and known to campaign on the continent. He fought on the same side as the Romans, not against them as Arthur did, but this is an easy point of confusion (or intentional change)

Geoffrey Ashe is the most well known proponent of Riothamus as Arthur, and he makes a fascinating case, but I feel that he only strongly identifies the continental campaign as belonging to Riothamus. I speak on this theory and Ashe's work in my substack article on Riothamus.

Most of his argument hinges on ensuring an interpretation that Riothamus crossed the channel from Britain to the Continent, however that is highly up for debate. Riothamus as a name is possibly a title, but could easily be a personal name.

No Riothamus appears in Insular Brythonic sources, and Ashe waves this away by just claiming that 'he's there, he's just called Arthur' which is fairly unsatisfactory in my opinion, as this places Arthur immediately succeeding Vortigern directly in power.

Riothamus does figure within the Breton lists and sources however, as a son of King Deroch II (likely Deroch I though, confused with Deroch II). Other than Geoffrey of Monmouth's word there is no compelling reason to believe there was a cross-channel high-kingship of Britons.

Vortigern as high-king likely did not hold sway over the kings of the north, and Arthwys as high-king in the north likely did not have power over the southern kingdoms during his time, much less in Armorica. This doesn't preclude some ambitious Kings from claiming they did.

The likeliest explanation is that Riothamus, the high-king of the Britons in Armorica, led a campaign against the Goth, which he brought via the sea instead of an overland march.

Later writers hear of this grand campaign to aid the Romans and this poorly attested figure is surely the same as the 'Great Arthur' the Britons speak of, and the legend grows, eventually picked up by Geoffrey as what he believes is genuine history.

Geoffrey melds a handful of figures (possibly knowingly, possibly unknowingly) giving us his Arthur, one rooted in both fact and fantasy.

Geraint of Dumnonia, and the Battle of Llongborth.

Geraint, a relatively unattested king of the kingdom of Dumnonia in southern Britain is the subject of the poem Geraint vab Erbin, or 'Geraint son of Erbin', a 10th century poem speaking of Geraint's deeds and death at Llongborth.

The poem relies on repetition of the phrase "In Llongborth I saw" reinforcing the heroism of Geraint's deeds in battle "In Llongborth I saw the rage of slaughter, And biers beyond all number, And red-stained men from the assault of Geraint."

Then seemingly from nowhere we get "In Llongborth I saw Arthur, And brave men who hewed down with steel, Emperor, and conductor of the toil."

Here Arthur and his men are stated to have been at the battle. Arthur is called 'amerauder' or Emperor, the earliest usage of the term in relation to Arthur, elevating him from King or even High-King to Emperor.

For those familiar with my work, you will know that I think Arthwys ap Mar to be one of the earliest figures behind the Arthurian Legends. He is not the only figure behnd them, but he is one of the main ones.

Arthwys seems to have been a sort of High-King in the north, and exercised a great deal of power, enough indeed to carve new kingdoms from other's territory, while others were shrinking.

What does this have to do with Geraint and the mention of Arthur? There is some evidence that Arthwys may have made as far south as Dumononia's neighbor Cernyw. That evidence is the Artognou stone.

As I have spoken about before in the thread above, Arthwys and Artognou may be very well related, and my friend

has gone even further and given a fantastic breakdown seen below. Follow him if you don't already.

If Artognou descendant of Colus, and Arthwys descendant of Coel are the same man, then that puts Arthwys in the south around the turn of the 6th century, to which the stone is dated. This is around the time of the Battle of Llongborth as well, sometime around 500-510ad.

This memory of Arthur and his men at Llongborth may indeed be a real possibility. If this was Arthwys on a trip to the south (possibly diplomatic at first as indicted by the Artognou stone) it has large implications for Arthwys' ability to project power.

This is not as surprising as it would initially seem though, as Arthwys probably functionally controlled a territory as large or larger than his great-grandfather Coel did, who ruled one of the largest kingdoms of his time.

This hazy memory of 'Emperor' Arthur in a poem singing praise about a southern ruler seems a non sequitur at first, but when considered with the Artognou stone paints an interesting picture of a battle Arthwys may have participated in post-badon in the south.

The Burial of Arthur?

In 1190 or 1191, the monks of Glastonbury Abbey exhumed two bodies found under a stone slab, 7 feet underground, with the lead cross seen in the image below. This cross claimed "Here lies buried the famous King Arthur in the isle of Avalon with his second wife Guinevere"

Mind you, Glastonbury Abbey nearly burnt completely to the ground in 1184, and the main draw for pilgrams to the Abbey was the 'Old Church' which was destroyed, and the monks may have had potential good reason for a fabrication of such grandiosity.

There are some interesting things about it though, the first being it's use of Artvrivs or Arturius, a seldom used latinisation of Arthur, that generally is only seen prior to the 8th century, and second that Guinevere is not Arthur's first wife. As my friend @lmrwanda pointed out in a fantastic article on the name Arthwys "Arthwys, Latinized as Art(h)usus could very easily be realised as Art(h)urus, especially by a speaker familiar with the remarks of Varro on this phenomenon and of a “classicising” bent."

Arturius is not a far cry from this, and while the finding of the cross and grave is suspect, it is an intriguing find. The monks themselves could have gone further if they had wanted to perpetuate an even greater hoax, such as the grave of Joseph of Arimathea.

This gives small assurance that it is genuine, however the mention of Guinevere as Arthur's second wife (the original inscription of this mention, though corroborated by multiple writers, supposedly on the back of the cross, is lost to time unfortunately) does resonate.

In my recent article on the abduction of Guinevere, taking a look at the earliest form of the trope, which is from carvings on a Cathedral Archivolt in Modena, Italy, I pointed out the possibility that while my favored candidate for Arthur supposedly married Cywair of Ireland-

Guinevere could have easily been a second wife, as Cywair was said to have become a Woman of the Church in her old age, and founded a church in Llangywer in Gwynedd, and is remembered as St. Cywair. Arthwys/Arthur could have easily remarried.

So if we are to take this burial as genuine, how does a king that died at Camboglanna, and supposedly was interred at Avalon, (which my friend @p5ych0p0mp has shown is almost certain Aballava on Hadrian's Wall, you can find his articles on my substack) Come to be at Glastonbury?

There is a possibility that he was reinterred at Glastonbury some time after his original passing, possibly upon the death of this second wife, Guinevere. This wouldn't be much of a stretch, as Glastonbury was a holy site of note even prior to the Romans!

The church was of significant importance in the post Roman period, and may have been a desirable place for reburial. This is of course speculation, and generally is seen as supporting a southern Arthur hypothesis, as well as Glastonbury as Avalon.

Glastonbury itself is filled with more Arthurian 'woo' than you can shake a stick of Oak at, but the theories on it being Avalon are generally shaky, but it could be possible, as Gerald of Wales mentions it being known as that in the past.

Regardless of the veracity of the burial, it is a part of the puzzle to understand how the later composite Arthur has come to be, and is thus valuable in our search, even if it doesn't support my Arthur of interest, Arthwys of Ebrauc.

Chronology Methodology

A good example of how working through prospective dating for these figures works. If you can fix a person to a fairly certain DoB, you can then work backwards to get an upper range, assuming all older fathers (48 year generation) compared to all younger fathers (20 year)

This gives you a range of dates that any of these figures could have possibly been born. With every generation this gulf gets bigger by 28 years, giving Coel a range of 120 years!

With two figures this can get you decently close to when these people may have lived, especially if you have examples of a likely early father, a likely late father, and a likely average father.

With the addition of a line of likely older fathers which in this case we get with Ceredig of Elmet we can dial things in even better.

So then by looking at our duplicates in all three (this case Coel and Ceneu) this can give us a very likely rough DoB for these figures, coming out to roughly 375 for Coel, and 409 for Ceneu. Mar with only two entries gives us 455 for his average.

This is not all particularly exciting, but can show you how three men technically in the same generation (Ceredig, Peredur, and Urien) can have close to a 40 year span of births. Keep in mind all of these final dates could be out as much as 10-15 years or so in either direction.

But this is an important exercise in determining rough chronologies for these figures that are otherwise unattested in hard historical documents.

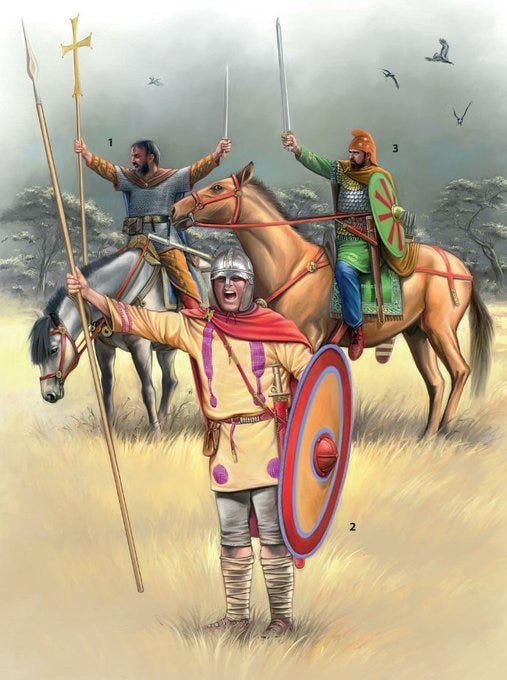

The Alleluia Victory of Germanus

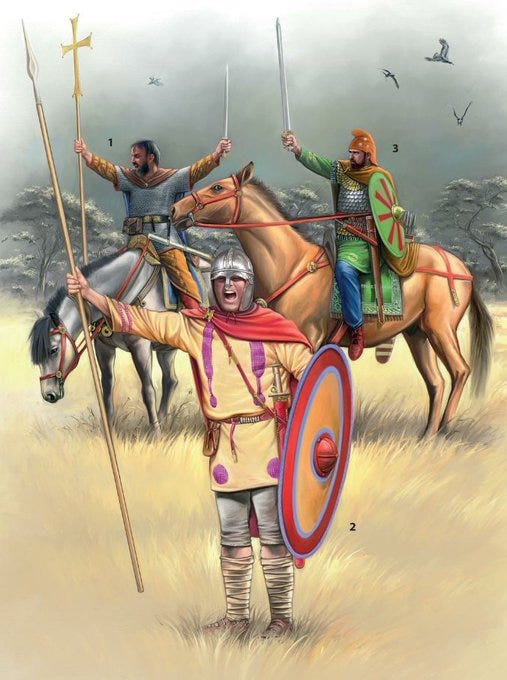

Around 429a.d. Germanus was tasked with helping to suppress the Pelagian heresy that had taken root in Britain. While there Germanus led the people in an immense victory against a combined force of Picts and Saxons.

Placing his warband in a valley between two high mountains he instructed them to shout when he gave a sign. Upon the enemy's approach Germanus shouted three times, Alleluia, which his army echoed.

The holy cry echoed throughout the vale, and the raiders thought they were set upon by the entire host of Britain. They promptly dropped their weapons and fled.

This bloodless victory became known as the Alleluia victory, and was recorded by Constantius of Lyon in his work Vita Germani around the year 480, roughly 50 years after the victory.

An interesting thing about this is that the Britons in the area looked to Germanus for military leadership. Germanus was possibly Dux Tractus Armoricani et Nervicani, and may have been the most senior commander there, but it is still curious no British commanders are mentioned.

This aligns well with Cunedda's later occupation and establishment of the Kingdom of Gwynedd, filling a vacuum that Irish raiders were eager themselves to fill. Another interesting tidbit to help give a better view of the big picture.

Pabo Post Prydain, The Pillar of Britain, and the questionable chronology behind him.

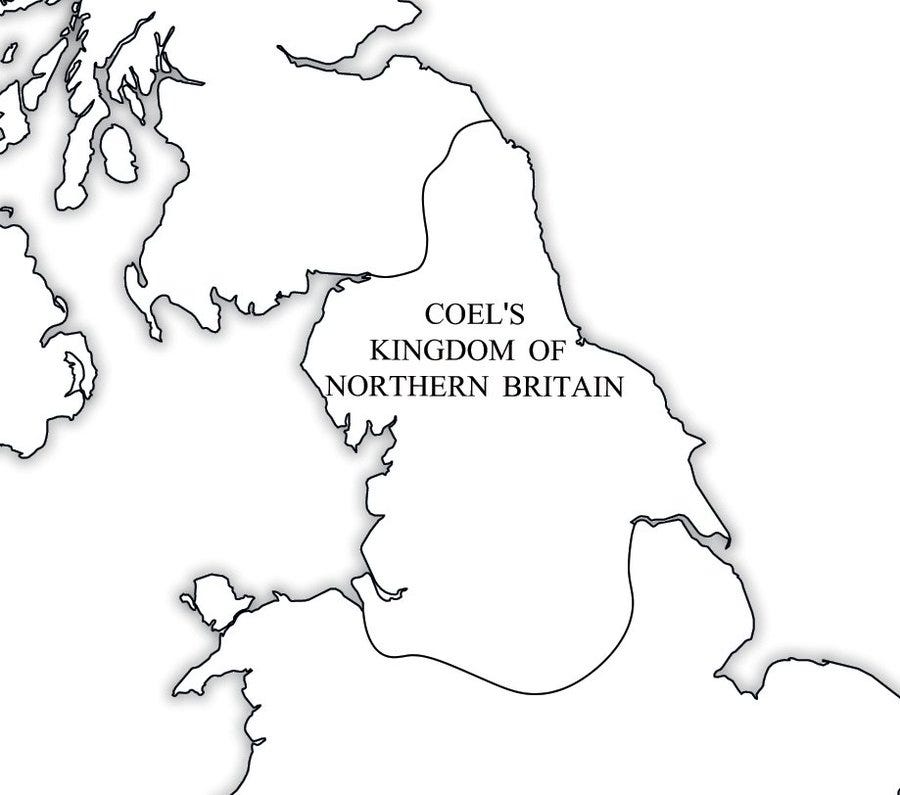

In the wake of Roman expulsion/exit from Britain, numerous local leaders carved kingdoms out for themselves. One of these men was Coel Hen (the old), who founded the massive 'Kingdom of Northern Britain'

As was tradition among Brythonic kings, Coel's realm was split upon his death, first between his sons Ceneu and Garbanian, and then amongst their children, Ceneu's sons Mar, Gwrwst and Pabo, and Garbanian's son Dyfnwal Moelmud.

The earliest genealogy for Pabo lists him just as stated above, as a son of Ceneu and Grandson of Coel, however a latter tract lists him as a son of Arthuis ap Mar ap Ceneu. While I generally prefer the earlier tract, the later does have some merit.

If we assume that Pabo was born around the same time as his brothers Mar and Gwrwst this would give him a Floruit of roughly 470-500. This poses problems however, as it then sets his children roughly a generation too early.

Dunod, who is a contemporary of Urien, would be active around the time of Arthuis ap Mar, with this chronology. Even placing his birth around 500, at the end of the his father's floruit in this chronology he would have been in his late 80s when he makes war on Urien's son Owain

He would have also been 95 at his death in battle at the hands of the Angles of Bernicia. While we have accounts of older men leading in battle, and even fighting, this stretches belief a little. Making Pabo a son of Arthuis' can remedy some issues, but still causes other issues.

Pabo's son Sawyl causes one of these, specifically through his daughter, who was supposedly wife of Maelgwn Gwynedd, a figure who has a fairly certain Floruit of 520-550. If Arthuis had a floruit of 490-520 Sawyl's daughter no longer works as Maelgwn's wife.

There is a middle ground however, that works well and gets Pabo's descendants in a more reasonable place, which is generally the route I have gone with my chronology. Pabo has to be born fairly late in his father's life.

By shifting Pabo 15 years later than his brothers, things align much better. Pabo now is an elder contemporary of Arthuis and Llenneac ap Mar, with a floruit of 485-515. This allows for some leeway when placing his descendants.

This allows for Sawyl to be born earlier, right at the beginning of Pabo's floruit, in 485, and Sawyl's daughter was born at the beginning of his rough floruit of 505 this quite easily puts her in the right time to become one of the many wives of Maelgwn Gwynedd.

The allows then for Dunod to be born late to Pabo, giving him a birth of 515 (Possibly even later) making him a closer contemporary of Urien, still quite old for his later exploits, but much more reasonable overall, being 80 at his death instead of 95.

This is the process we must work from to try and create a chronology from these shadowy figures, with scant references and scant resources. Unfortunately we will never know whether this is 100% correct, but through this process and reasoning I think we can get close.

Yrfrai, one of the warriors remembered in Y Gododdin, his father, and an interesting implication.

It was usual for him to be mounted upon a high-spirited horse defending Gododdin at the forefront of the men eager for fighting. It was usual for him to be fleet like a deer.

It was usual for him to attack Deira' s retinue. It was usual for Wolstan's son-though his father was no sovereign lord that what he said was heeded It was usual for the sake of the mountain court that shields be broken through reddened before Yrfai Lord of Eidyn.

Yrfrai, here is clearly a warrior of the Gododdin, and fighting the Deirans specifically, however there is something strange about his father's name. Wolstan is not a Brythonic name.

Wolstan is likely a Brythonic rendering of the Germanic name Wulfstan, implying that Yrfrai was half Anglish. Wulfstan being "No Sovereign Lord" may reinforce this, as he could have been a mercenary or a high ranking exile who found a new home among the Gododdin.

Interestingly enough, there are quite a few mixed graveyards in the north showing similar arrangements, even fortresses showing use of Angle soldiers as well as Brythonic. It may not have been unusual to find a few Angles, Saxons, or Jutes loyal to a Brythonic King.

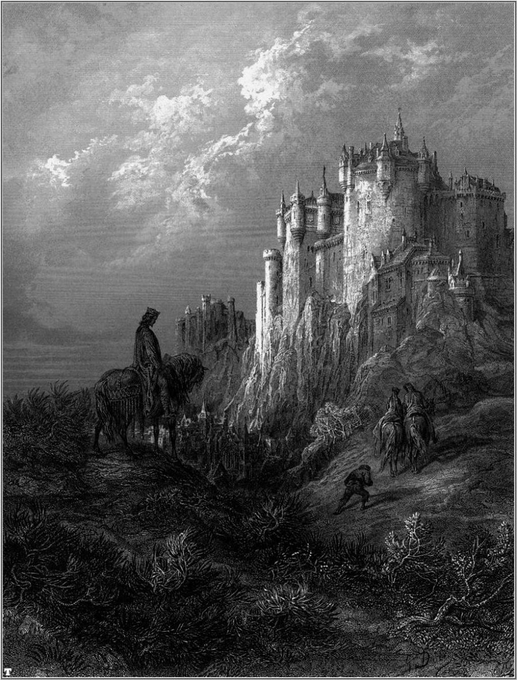

Arthurian Tropes: Camelot

Camelot brings to mind a shining medieval castle, a fortress fit for the greatest of rulers, but the real Arthur's citadel would have been much different than this depiction. Is there any potential historicity to Camelot at all?

The earliest mention of Camelot comes from Chrétien de Troyes' poem 'Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart'. Camelot barely makes a footprint here, only being mentioned once, and is instead in another manuscript replaced with the phrase 'con lui plot' or 'as he pleased'

This gives doubt to the any kernel of historicity to Camelot alone. While there are numerous place-names that can be skewed to fit and sound like Camelot, if Chrétien's original intent was to write 'con lui plot' these are all just fancies and can easily be shoved aside.

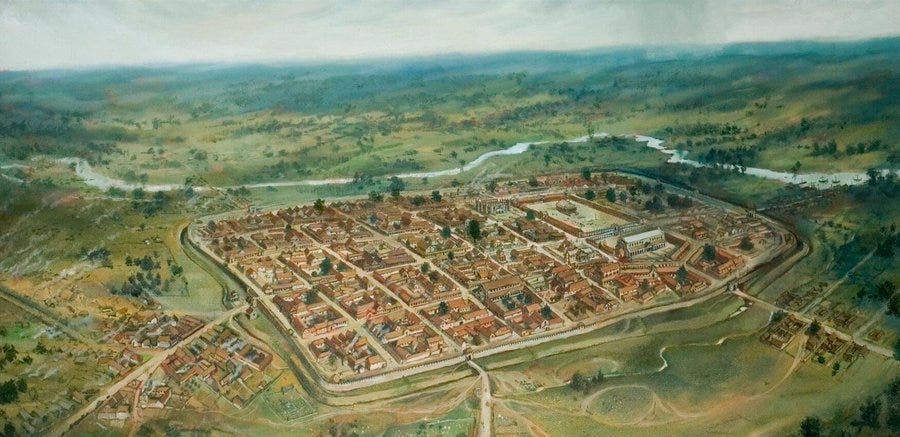

I will briefly entertain them anyway. One of the first places often mentioned is Colchester, known in Roman times as Camulodunum. The proximity of the name makes it intriguing, however this is an unlikely Camelot as it was taken fairly early during the Germanic invasions.

Another place shares a similar name to Camulodunum is seated in West Yorkshire, Cambodunum, now known as Slack Roman Fort. Cambodunum fell into disuse in the 2nd century, and shows little signs of occupation after, but was seated to control traffic from Chester to York.

Camelon, in the Forth valley, has been suggested as well, although the name is quite shaky, and may be a neologism coined in the 16th century. Boece was the first to mention it, but it seems likely its original name was Carmore or Carmure.

Another place shares a similar name to Camulodunum is seated in West Yorkshire, Cambodunum, now known as Slack Roman Fort. Cambodunum fell into disuse in the 2nd century, and shows little signs of occupation after, but was seated to control traffic from Chester to York.

Camelon, in the Forth valley, has been suggested as well, although the name is quite shaky, and may be a neologism coined in the 16th century. Boece was the first to mention it, but it seems likely its original name was Carmore or Carmure.

The looming giant here is Cadbury Castle, touted as Camelot by Leslie Alcock, and Geoffrey Ashe. It was known colloquially as Camalet for a time, there may even be a distant memory here. Cadbury was one of the most prestigious fortresses of it's day, and certainly fits the bill.

Keeping in mind Chrétien's words 'con lui plot' though all of these seem moot. That doesn't mean we're at a dead end though, as there are earlier works that mention Arthur's court. Celliwig is mentioned as Arthur's court in the story Culhwch and Olwen.

While Culhwch and Olwen provides little insight into actual history, it does provide us with a name and a place for Arthur's court, Celliwig, said to be in Cornwall. This would make Arthur part of the Dumnonian nobility, or a high-king with power over Dumnonia.

Geraint mab Erbin was king of Dumnonia at the time, and while it's possible the historical Arthur could have held court there as High-King it would likely have not been a permanent seat of power for him.

In a triad from Peniarth MS 54, Arthur is given as the Chief Lord of three places, Menevia, the aforementioned Kelliwic, and Penrionyd. The repetition of Celliwig is interesting, as well as the mention of Menevia, and Penrionyd.

This triad of course is reinforcing the idea of Arthur as 'High-King' having courts in the South, the West, and Penrionyd which is specifically mentioned by the triad as being 'in the North'.

This Triad itself is rife with anachronism, giving Maelgwn and St. Kentigern as contemporaries to Arthur, but there may be a little truth here too. Penrionyd has been identified with Rerigonium, which has been associated with the Picts.

Rhynie in Aberdeenshire has also been put forward as a possibility for Penrionyd, and may have been occupied by Pictish kings. As I have discussed before There are actually two Arthurs who may have been kings of the Picts

Menevia is easily identifiable as likely being in Pembrokeshire, which has an Arthur of it's own as well in Artuir ap Pedr of Dyfed. Artuir is quite late though to be the historical core of Arthur, though this still could have been his contribution to the composite Arthur.

Celliwig in Cornwall is not easily identified, with suggestions of Callington, and Kelly Rounds. These are not heavily evidenced, but there is some evidence (The Artognou Stone) for someone named Arthur to have been there as well.

Unfortunately there is not cut and dry answer as to where Arthur's court was seated at the end of the day. Carleon and Carlisle are also heavily associated with him, but they both have issues and merits to themselves as well. Carlisle often shows up in later material as Carduel.

King Edward I, who heavily modelled himself after Arthur held court in Carlisle while campaigning in Scotland. Perhaps he knew stories lost to us now? Henry II reinforces this in a charter calling the fort on the wall by Carlisle, Uxelodunum, 'Arthur’s burh'

Carlisle is intriguing for me as a proponent of a Northern Arthur, though it is likely that Merichion Gul or his son Cynfarch Oer were the proper lords of Carlisle during this time.

If my theories on the Northern Arthur are correct then it is likely that Arthur's court at least in his early reign, was in Ebrauc or modern York. Ebrauc fell to the Angles in 580 and was quickly forgotten as a once powerful Brythonic kingdom.

As such Arthur's court is then moved in each iteration to wherever it needs to be. A poet in Wales would write of his Welsh court. A poet in the South would write of a Southern court. A Breton, of a Breton court, eventually until all trace of the original is forgotten.

We are then left with an almost entirely fictional court, possibly made up, possibly even a copyist error, that is now immortalized as 'Camelot'

Cadrod Calchfynydd and Amhar ap Arthur, an odd connection.

When looking through the many different pieces of the Arthurian puzzle, one sometimes stumbles on something strange or unexpected. One of these unexpected things centers around a great-grandson of the northern King Arthur, Arthwys ap Mar

Cadrod Calchfynydd was seemingly king of the little attested kingdom of Calchfynydd, which is generally lost to history other than some vague possibilities. One of these possibilities, and the most likely scenario is that this was a kingdom in the Hen Ogledd, or Old North.

This kingdom was likely centered around modern day Kelso, and while others have placed Calchfynydd in the Chilterns, it is an unlikely possibility, as Cadrod is the great-grandson of Arthwys ap Mar, and would have ruled in the late 6th century.

Brythonic rulers in the south were not unheard of during this period, but the likelihood of the great-grandson of a King of Ebrauc to carve out a kingdom for himself in the south strains credulity in a time when most Brythonic kingdoms were on the back foot.

Calchfynydd itself was probably set up as a buffer state, during Arthwys' late reign. With all of this considered, I think it highly likely that Calchfynydd was centered on Kelso, which was known as Calchow or Calkou in it's early records.

Cadrod appears in Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd, a genealogy of these northern princes, and his lineage is given as Cadrod-Cynwyd-Cynfelyn-Arthwys-Mar-Ceneu-Coel. This is generally a fairly accurate assumption, though there may be reason to believe that Cynwyd was possibly grafted on.

Cynwyd is conflated with a Cinuit found in the genealogies of the kings of Alt Clut, conflating the two figures, and giving them common descendants who were otherwise unrelated. It could even be that Cynwyd was an interpolation to bolster a claim.

This is a further possibility when it come to the chronology of Cadrod's descendants. The problems associated with this are not impossible, as many make assumptions of using 40 and 30 year generations, when 27 year generations work better over long periods.

Regardless of all of these issues, there is an alternate genealogy for Cadrod, which gives him an unusual father. The Aedd Mawr pedigree as it is sometimes called, lists Cadrod as 'Calchfynydd' and his father as Enir... or I would propose Amhar

This is an interesting possibility here, knowing that Cadrod is either the grandson or great-grandson of Arthwys ap Mar, who is most likely one of the initial inspirations for the King Arthur of legend.

Amr or Amhar as he is later known is one of the earliest attested sons of this later legendary Arthur, being found in an entry in Nennius' Historia Brittonum in a second appended at the end called "De mirabilibus Britanniae" Within it a tomb is described as belonging to Amr

Amr is said to be the son of 'Arthur the Soldier' buried in Ercing (an association that may have been appended later via association with Athrwys ap Meurig) Anir is also seen in place of Amr, further strengthening the connection between Enir and Amr.

While the grave of Amr is unlikely to genuinely be the resting place of a son of Arthur, it still gives us an interesting possibility, that Amr or Amhar was a real person, and was likely Cynfelyn ap Arthwys, the father (or grandfather) of Cadrod.

Anir or Amr could have been an epithet or alternative name for Cynfelyn, otherwise lost to time, thus linking the two possible ancestors for Cadrod quite conveniently.

This speculation is generally unprovable, and as such must be taken with a grain of salt, but it is an interesting coincidence that Cadrod appears as a great-grandson of the Northern Arthur in one genealogy, and then as the grandson of the legendary Arthur in another.

Gartnait, a Pictish form of Arthur?

There is a figure in the Pictish kings list known as Gartnait I, who ruled from 531 to 537. Gartnait has been proposed by some as one of the inspirations behind Arthur. What if Arthwys and Gartnait were in fact the same person?

Interestingly enough, there is another Gartnait found amongst the kings of the Picts, Gartnait II, who was roughly contemporary with another famous Arthur, Artúr mac Áedán of Dal Riata. Artúr himself has become a more in vogue candidate for the historical Arthur in recent years.

This poses the interesting possibility that Gartnait is in fact a pictish form of the name Arthur. It has been suggested that Artúr's mother was Domelch, and ruled the Picts by claim from his mother. Áedán's sons are listed in Senchus Fer nAlban, and Artúr is curiously absent.

Instead one of his sons is given as Gartnait, who is unattested elsewhere. Artúr is instead given as Áedán's grandson, which is generally thought to be an error. It would seem that the error is accounted for as Gartnait was probably Artúr.

This arrangement of Kingship would come to an end with the Battle of Miathi, where Áedán won a costly battle. "from Aedan's army, three hundred and three were killed as the saint had also prophesied" The 'barbarian' Miathi took their toll on Áedán's ambitions.

The Miathi are probably the same tribe described by Cassius Dio, probably living just north of the Antonine Wall near the River Forth. This may have been an attempt by Áedán to solidify power in the North, with Artúr strongly supporting him as King of the Picts.

Things did not go well and instead Áedán's sons Artúr and Eochaid Find both were lost in the battle. Gartnait II's rule ends right around the time of the accepted dates for the Battle of Miathi, similarly to how Garnait I's ends the same year as Camlann. Very curious.

St. Derfel The warrior-turned-monk who survived Camlann.

Derfel has found much modern fame through Bernard Cornwell's book series "The Warlord Chronicles" a gritty take on Arthuriana, with Derfel as a protagonist, absorbing many of Bedwyr/Bedivere's qualities

There is a kernel of truth to Derfel however. Derfel is generally called a son of Hywel or Howel, though one genealogy calls him the son of Hywel the Great, and another calls him his grandson.

Hywel the Great was said to be the son of Emyr Llydaw. Emyr generally is held to mean Emperor, and Llydaw was a name for Brittany. Emyr Llydaw is often considered by many to be synonymous with Geoffrey of Monmouth's Budicus, and is used in the Welsh Brut y Brenhinedd

The Life of St. Euddogwy from the Book of Llandaff claims that Budic, with his son Hywel was exiled by a usurping cousin, and sought refuge for a time in the court of Aergol Lawhir of Dyfed. This is important in establishing a potential Chronology for Derfel himself.

Hywel was a young man while Aergol was ruling, and we can generally date Aergol to the generation before Gildas, who was likely born in the 490s. If Derfel was the son of Hywel the Great he could have been born any time between 480-520 roughly.

If Derfel was the grandson of Hywel this extends it to a possibility of 500-540 roughly. This is neccessary, as it is said that Derfel found service in Arthur's warband as a young man, and Arthur was most likely active from the 490s until his death in 537 at Camlann.

According to tradition Derfel was a powerful warriors and was one of the seven survivors of Camlann, surviving on "His strength alone". having the 537 date for Camlann further tunes his dates, with him likely being born no later than 520.

Interestingly Geoffrey links Derfel's 'father' Hywel with a few of Arthur's battles. First with Dubglas, then with a siege of York, as well as The Battle of the Caledonian Forest. Dubglas is a well known entry in Nennius' list of Arthur's Twelve Battles in his Historia Brittonum

The Caledonian forest is well known as well, Cat Coit Celidon, York is at first glance harder to place, but as I have discussed before, is likely Arthur's ninth battle in Nennius "The City of the Legion". This is interesting as all of these are found in Northern Britain.

As many who are familiar with the bulk of my work know, I am a proponent of the theory of a Northern Arthur, specifically a king of Ebrauc, Arthwys ap Mar. While Geoffrey's work is far from evidence, it is nonetheless interesting to note.

While Derfel is often associated with Wales it is still quite possible that he found himself in the warband of a Northern Arthur, or even for Rheged, as Camlann, the only battle directly associated with Derfel, sits on Rheged's northern border with Caer Wenddoleu.

Links between Northern Wales and the Hen Ogledd are generally forgotten, but can been seen within Y Gododdin, as well as tradition of Cunedda, a prince of Manau Gododdin carving out the kingdom of Gwynedd in North Wales.

"When there were at Camlan men and fighting and a host being slain, Derfel with his arms was dividing steel there in two" After fighting at Camlann, Derfel retired to the life of a monk, some traditions associating him with Llandderfel and others with the monastery of Llantwit

The Church at Llandderfel at once point held a relic of Derfel's known as his 'Walking-Stick', as well as a wooden carving known as 'St Derfel’s Horse', which in fact is the remnants of a Stag, an animal often associated with many of the wandering Saints of Wales.

supposedly the statue originally depicted Derfel as a warrior on Horseback (in reality a stag) and a prophecy held that it would one day burn down a forest. At the behest of Thomas Cromwell during the reformation, it did.

Cromwell had Derfel removed from the stag, chopped up and used as fuel for a bonfire used to execute a Franciscan friar named John Forest.

Derfel was eventually said to have served as the abbot of Ynys Enlli, Bardsey Island, a position formerly held by a cousin of his St. Cadfan who also established the religious community at Tywyn prior to becoming abbot of Ynys Enlli

Derfel died peacefully on April 6th, 560, and his feast day is on the 5th of the same month. While everything attributed to him cannot be proven of course, it is very likely that Derfel was in fact a real figure, and possibly a warrior of Arthur's

Taliesin's poem Kat Godeu, and some possible historicity.

Kat Godeu exists as an interesting companion to Myrddin's poem "Yr Afallennau". While the mythical enchanter Gwydion makes an appearance animating trees to help fight the battle, it's possible that it commemorates a real battle, much like Yr Afallennau does with Arfderydd.

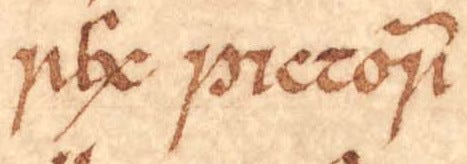

The inclusion of the line "Rac prydein wledic" The Wledig of Britain. Wledig is usually used for localised kings/landholders, but in two instances it is applied to figures who are remembered as rulers of all Britain, first to the Roman Usurper Magnus Maximus, and second to Arthur

If this poem is about Arthur, it very well may be describing, in a mythologised fashion Arthur's Battle of the Caledonian Forest. My friend @p5ych0p0mp has already speculated that Taliesin's work Preiddu Annwn is a similarly veiled account of Arthur's last battle Camlann.

This gives a precedent to the weaving of mythical figures and tales into historical events by a skilled Bard, much like the veiled double-reference to Mar ap Ceneu, equating him with Mars-Alator, a God in Kadeir Teyrnon.

@p5ych0p0mp has often spoken to me of Camlann and Catraeth echoing, and I agree there, civil tensions coming to boil and erupting in an apocalyptic civil war, but I think that Arthur's battle of Cat Coit Celidon also is echoed by the battle of Arfderydd.

After the chaos of Arfderydd, Myrddin fled into the Caledonian forest, giving once again that feeling of an echo. This combined with the potential of both being linked through poetry associated with trees further piques my interest.

I may go dig in with more depth in a later thread on Kat Godeu, and it's links to The Battle of the Caledonian Forest, but for now, just some small musings here.

The theory of an early Battle of Catraeth and a nephew of Arthur's, Guallauc ap Llenneac.

While I have written a fair amount on the idea of the Battle of Catraeth taking place roughly twenty years earlier than general consensus holds I thought it would be worth touching on a new potential connection.

Within 'Moliant Cadwallon' a song of praise to Cadwallon ap Cadfan it is told that 'fierce Guallauc wrought the great and renowned mortality at Catraeth' This of course links Guallauc to the famous battle, which is an important step, but is there any other evidence?

Around 590 Urien of Rheged made war upon the Angles of Bernicia to try and remove the foothold they had in the north. He was aided in a grand northern alliance, with his fellow Brythonic kings, Guallauc of Elmet, Morcant of Bryneich, distant cousins, and Alt Clut's king Rhydderch

This assemblage of the most powerful Brythonic kings in the north excludes two previously powerful polities, Ebrauc, and Gododdin. Coincidentally, it would seem that these were two of the major aggressors against Urien at the Battle of Catraeth.

It would seem that the early Catraeth accounts for Guallauc's appearance in this alliance, as well as the lack of presence from Gododdin or Ebrauc, Gododdin waning, and Ebrauc completely taken by the Angles of Deira, and then known as Eoferwic.

There is another mention though that further strengthens Guallauc's presence at Catraeth, and that comes from Taliesin's poem 'Cadau Gwallawc' or 'A Song of Gwallawc ap Lleenawg'

'A battle in the presence of Mabon. He will not mention the contradiction of the saved. A battle in Gwensteri, and thou subduest Lloegyr. A darting of spears there is made.'

Owain ap Urien is sometimes equated to the mythical figure of Mabon, and Gwensteri is probably the same battle as the battle mentioned in another poem attributed to Taliesin 'Gweith Gwen Ystrat', which is likely the victors point of view of the Battle of Catraeth.

So it can be surmised then that Guallauc was present with Urien and Owain at Catraeth, once again leading to further evidence that Catraeth was fought not in 600 between the Gododdin and the Angles, but in 580, a civil war between warring factions of Britons.

The Deaths of Peredur and Owain of Ebrauc

I was mulling over the triad that features Peredur and Gwrgi's deaths the other night, and was moved to write a short story about it. By reconstructing as much of the situation as we can you can almost see their feelings and motivations at the time.

The twin-kings of Ebrauc appear twice in the Annales Cambriae, first in an entry discussing a battle they fought against their cousin Gwenddoleu ap Ceidio in 573, The Battle of Arfderydd, where Gwenddoleu's bard, advisor, and also cousin Myrddin went mad upon seeing the slaughter

The second dates to 580 and reads 'Gwrgi and Peredur sons of Elifert died.' The triads fill in the gaps in our information here, telling us more information about how the Sons of Eliffer came to meet their end.

"The War-Band of Gwrgi and Peredur, who abandoned their lords at Caer Greu, when they had an appointment to fight the next day with Eda Great-Knee; and there they were both slain"

The situation leading up to both of these events in the Annals is actually fairly easy to determine. The main kingdom to benefit from the absence of Gwenddoleu was Rheged, which was under the power of the Arthur of his day, Urien ap Cynfarch, a distant cousin to Peredur and Gwrgi

Urien acted as a high king during his rule in the north, uniting other kings under his banner to wage war, and controlling land that was likely in kingdoms that he himself didn't rule directly. One example of this is the infamous Catraeth.

Catraeth has long been associated with modern Catterick, which itself would have been roughly within Ebrauc's territory at later half of the 6th century, however Urien is called "Lord of Catraeth" and is said to lead the "Men of Catraeth".

As I have discussed before it is more than likely that Urien was in fact the enemy of the poem Y Gododdin, a series of elegies commemorating fallen warriors, one of which is likely Peredur of Ebrauc.

Catraeth has long been associated with modern Catterick, which itself would have been roughly within Ebrauc's territory at later half of the 6th century, however Urien is called "Lord of Catraeth" and is said to lead the "Men of Catraeth".

As I have discussed before it is more than likely that Urien was in fact the enemy of the poem Y Gododdin, a series of elegies commemorating fallen warriors, one of which is likely Peredur of Ebrauc.

Prior to Urien, Peredur and Gwrgi's father Eliffer would seem to have been a sort of high-king, if not on merit, at least on the name of his illustrious father, Arthwys, who is very likely the initial inspiration for King Arthur.

Arthwys as well ruled as a high king, and may have controlled territory all the way from the Midlands into Pictland (much of this can be found on my s**s***k which you can find a link to in my bio)

A narrative becomes apparent here. Urien who had filled the vacuum left by first Arthwys, then Eliffer, ruled as regent for the young twins of Ebrauc, stationed at the old roman fortress in Catterick.

Once coming of age, and becoming kings in their own right, enmity began swelling between some of the northern leaders towards Urien, especially after Arfderydd, a battle he didn't participate in but still reaped the benefits of.

Gwallog the king of Elmet was early on a staunch ally of Urien's it would seem. Similarly he did not participate in the battle at Arfderydd, but he did alongside Urien at Catraeth. Gwallog's kingdom bordered Ebrauc, and within Y Gododdin a man named Madog Elfed (Elmet) leads men.

Gwallog may have been dealing with a splinter shearing off from his own kingdom as well, leading to him strengthening his ties to Urien. Madog seems to have been a man of status, either a rogue noble, or possibly even a disgruntled son.

Eventually a contingent of dissatisfied nobles planned an attack on Urien at his stronghold of Catraeth. Mending ways with their old enemy, The Gododdin, they made for war. This ultimately led them to their deaths at Caer Greu, a poetic flourish for Catraeth, 'Fortress of Blood'

In my short fiction story released yesterday I took this to it's fullest extent, with them instead of being abandoned by their warriors on the battle's eve, being abandonded mid-charge.

No time to think on what has happened, only the thoughts of betrayal and attempts at survival ringing through the twin-kings' heads. These were grandsons of Arthur himself, and yet their men choose to withdraw when facing Arthur's successor to high-king in the North, Urien.

Rarely does history illicit an emotional response from me, especially my work on the Brythonic Heroic Age. Camlann has a palpable futility and melancholy to it, as well as the much later 18th century Battle of Culloden, which I had ancestors fall at.

Peredur and Gwrgi's deaths really struck me though. You can view it through the lens of the jealously of spoiled brats if you like, or the lens of stolen birthright. They were Arthur's grandsons, and were able to command warbands themselves, yet Urien reigned supreme.

Ultimately Urien met a death at the hands of betrayal as well, dying at the behest of Morcant of Bryneich, a king on the backfoot loosing territory daily to the Angles, a king who was allied to Urien at the time, but once again jealousy struck a mighty blow.

The Volcanic winter and Plague in the mid-500s certainly weakened the Brythonic kingdoms of the north, but in the end it was the Jealousy of kings that drove the final nails in their coffins.

Tristan ap Tallwch, or Drest son of Talorc?

It is interesting that Tristan of Tristan and Iseult fame, likely has his earliest appearance as a passing mention in The Dream of Rhonabwy, where he is named Tristan son of Tallwch.

The 'Tristan Stone' in as it is often called is a marker for a man named Drustanus, son of Cunomorus, which has often been assumed to be evidence for the existence of Tristan, and placing him in Cornwall, at least at the time of his death.

Cunomorus is a latinized version of Cynfawr and has been assumed to be the King Mark of the original tale. While I find this unlikely it is interesting to see the two names in such close proximity.

Interestingly there is another angle, and it involves a figure from the Pictish kings lists. There are many Drests (the original form of the name), and at least three were contemporary to King Arthur himself.

Drest II, or Drest Gurthinmoch, happens to appear a generation after another king named Talorc. Pictish kingship generally passes through the mother, but there are possible exceptions to this, and Drest II is not given a mother.

Back to the earlier mention in The Dream of Rhonabwy, Tristan son of Tallwch bears a striking semblance to Drest son of Talorc, and given that Drest II is known by an epithet, it is possible that he was an exception to the general rules of Pictish kingship.

There is also the fact that Meirchion Gul and his son Cynfarch (Cunomarcus) Oer of Rheged were also contemporaries of Drest, with Cynfarch even being remembered in The Dream of Rhonabwy as well, as 'Mark the son of Meirchion'

Could be a possibility that much like many other tales with origins in the Hen Ogledd, the setting was transported to the remaining Celtic areas of Britain. Tristan and Iseult may be a romanticized memory of a war between Rheged and the Picts in the late 5th or early 6th century.

The doomed lovers feature in a few of illustrations from my Colouring Book, which you can find below. https://amazon.com/dp/B0CKBDF1MT

Pa Gur: Arthur’s roster of heroes

WHO IS THE GATE-KEEPER? 'Glewlwyd Mighty-grasp. Who is asking?' 'Arthur and Fair Kei.' 'Who goes with you?' 'The best heroes in the world.' The opening to the fragmentary poem Pa Gur, notoriously difficult to translate. It may contain some early pre-Galfridian tradition though.

There is major disagreement on the date of origin for the poem, with most scholars favoring no later than the beginning of the 12th century, while more speculative estimates place it even as early as the 8th century. Somewhere in between the two extremes is probably more correct

The cast of 'The best heroes in the world' within the poem begins to cement the modern conception of Arthur's knights. Familiar faces such as Chei, or Sir Kay, and Beduir Bedrydant, or Sir Bedivere are present, though more distant figures like Kysteint son of Banon, appear too.

The roster of heroes:

Mabon son of Madron, the man of Uthir Pendragon,

Kysteint son of Banon,

Guin Godybrion.

Manawidan son of Llyr

Manauid

Mabon son of Melld

Anguas the Winged

Lluch Llauynnauc

Here real men mingle with gods within Arthur's retinue. Mabon is either the god Maponus or the poetic name for Owain ap Urien, Guin, Manawidan, and Lluch all have origins as gods, (though Lluch Llauynnauc may be a composite of the real figure Llenneac ap Masguid/Mar)

The poem contains many tantalizing fragments to stories that are now lost to us, such as 'The Fall of Celli' "When Kelli was lost, there was fury. Kei would be entreating them as he continued to hew them down. Though Arthur laughed"

Possibly a reference to Arthur's court at Celliwig, as seen in the Triad listing the 'Three Tribal Thrones of the island of Britain' in which Arthur is chief prince in three places, Mynyw in Dyfed, Celliwig in Cernyw, Pen Rhionydd in the North.

It also corroborates one of the battles in Nennius' battle-list, Tribruit, here seen as Trywruid. 'Before four-sinewed Beduir on the shores of Trywruid in the struggle with Rough-Grey (Garwlwyd, a possible werewolf like figure) he was fierce in affliction with sword and shield.'

Much of the remaining fragments are boasting of Cai's prowess and power. Cai is a lord of battle, a cattle raider, a heavy drinker, a general who refused to take hostages.

Arthur's battle of Mount Agned which is adjacent to Tribruit in Nennius likely makes an appearance, with Cai fighting the 'cinbin' or Dog Heads of Edin 'In the Mount of Eidin he fought with dog-heads. Every group of a hundred would fall. There fell every group of a hundred.'

Cai appears as a slayer of witches and lions, as well as combatting the fierce monster cat 'Cath Paluc' "Fair Kei slew nine witches. Fair Kei went to Anglesey to destroy lions. His shield was polished against Cath Paluc"

Cai raids cattle (possibly from Ambrosius Aurelianus): "Before the kings of Emreis I saw Kei hasten, leading plundered livestock, a hero long-standing in opposition."

The mention of Emreis here is interesting, better known as Ambrosius, showing an early separation of Arthur and Ambrosius as different figures, casting further doubt on identifying him with Arthur.

Cai drinks: "His revenge was heavy. His vengeance was pain. When he drank from the ox horn, he drank them by fours."

The picture of Arthur and his battle-lords here is quite different, and far removed from the chivalry and shining armour of Mallory's Le Morte d'Arthur, these men are heavy drinking dark age warlords, who take no hostages, and lay their enemies low by the hundreds.

Sadly the poem cuts off before Arthur can lay forward further boasts of his men's exploits, and who knows what other traditions could be corroborated or expanded upon had the rest of this poem been preserved.

Regardless of it's difficult and fragmentary nature, it is still valuable to see how this early Arthur was viewed, even if it's at least 400 years separated from his life.

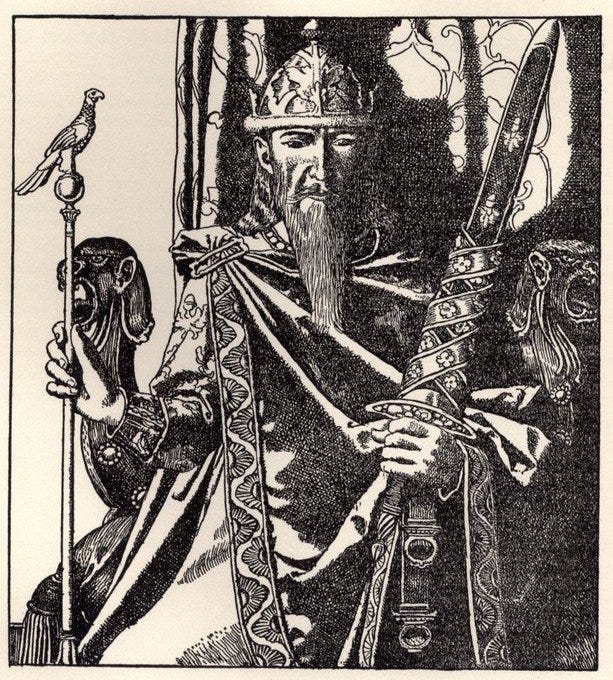

Dyrnwyn, one of the Thirteen Treasures of Britain, the sword of the famous Rhydderch Hael, king of Alt Clut

Dyrnwyn is usually described as thus "White-Hilt, the Sword of Rhydderch Hael: if a well-born man drew it himself, it burst into flame from its hilt to its tip."

Rhydderch in fact has his epithet Hael (generous) because of the sword "And everyone who used to ask for it would receive; but because of this peculiarity everyone used to reject it. And therefore he was called Rhydderch the Generous."

Other versions cast it as a worthy man being unburned, while unworthy men would be burned by the flames should they attempt to wield it. Interestingly Dyrnwyn's name bears similarlities to the epithet of Cadell of Powys, a grandson of Vortigern.

Cadell was known by the epithet Ddyrnllug or 'Gleaming-Hilt' a slight difference to Rhydderch's 'White-Hilt'. This may be coincidental, or even represent an earlier semi-common naming convention.

Some speculation has been made that these are both potential inspirations behind Caledfwlch, the sword of Arthur, which eventually morphs into Excalibur.

Caledfwlch bears linguistic similarities with the Irish Caladbolg, although this seems to similarly stem less from a common mythical descent and more from a common linguistic origin, both likely being related to an earlier generic term for Sword.

Dyrnwyn is still interesting because it is one of the few 'magic' swords wielded by a Brythonic ruler who is considered as 100% genuinely historical, as Rhydderch is fairly certain to have flourished in the late 6th and early 7th centuries.

I may eventually put out a piece looking over all of the treasures, as many of their owners are found as genuine historical figures, with only a little myth sprinkled in.

A Short note on Uther

Mine is the fierceness that turned on all foes.

It is I who am the prince leading on in darkness.

-the Death-Song of Uthyr Pen

Almost certainly a pre-Galfridian reference to the man that eventually is named as the father of the famous Arthur himself.

Who this "terrible chief" actually was is up for debate, and my friend @p5ych0p0mp and I have both theorized a couple of different possibilities. The first being that Uthyr or Uther is Arthur himself, and an epithet became transmuted into a father.

This can be seen with a singular copy of Nennius that says Arthur was known as 'mab Uter' or "terrible son" with some interpretation @p5ych0p0mp has surmised that "The Death-Song of Uthyr Pen" is in fact Arthur's death song. This epithet becomes a father's name by Geoffrey's time

Thus Geoffrey of Monmouth's father of Arthur, Uther Pendragon is born. There is another alternative route involving one of the sons of my favorite candidate for the first Arthur, Eliffer ap Arthwys.

Eliffer is commonly known in Latin as ElUTHERius, and in a triad that normally lists his three children as Peredur, Gwrgi, and Arddun (remember the dd is the same as an English soft TH, though she is sometimes called Ceindrech). One single version corrupts Arddun to ARTHUR

Arthur ap Elutherius, then appears in a particular manuscript that Geoffrey of Monmouth may have even seen. It then stands that Uther's Death-Song could in fact be about Eliffer.

Many of the things that stand as links to Arthur in the poem could easily apply to Arthwys' likely eldest son Eliffer, who likely acted in a large peacekeeping and border securing commander late on his father's life.

Faces of Arthur pt. 1: Many potential figures, many potential problems.

While I believe that a single traceable figure was likely the first Arthur, the Arthur of the early Bards, and the Arthur of Nennius, by the time of Geoffrey of Monmouth Arthur had become a composite.

The question remains, who does this composite encompass? How many figures could have contributed, are they drawn in to bolster the fame of the original Arthur, or was it accidental? These are difficult questions to answer, but there are a few leads.

The most obvious figure to look at first is Ambrosius Aurelianus, a figure we can confirm as a Historic figure, known through the writings of Gildas. Many have pored over Gildas' words to make an attempt to equate Arthur with Ambrosius, and have made compelling attempts.

The literal reading of the texts confirms that Ambrosius was a Warlord at least who fought against the Saxons, two generations before Gildas was writing, as Gildas mentions contemporaries to the time of his writing as being Ambrosius' grandchildren.

His family was of high status, and his parents perished in the initial Saxon wars. Ambrosius is then said to have given the British victory against the Saxons, but the British won sometimes and the Saxons others.

Gildas then goes on to add that after some time has passed, and the implication here is that it was more than a few years, that the battle of Badon was fought, and the British won a great victory there like never before. Frustratingly, the commander of this battle remains unnamed

Some have used this to connect Ambrosius as the victorious general of Badon, but unfortunately that doesn't seem to be the implication here. The only person ever directly attributed with winning Badon in other texts is Arthur.

One could then stretch and say that Arthur may have been a nom de guerre, or an otherwise acquired name, or possibly a birth name, but there is once again little evidence to draw from on this.

There is also the issue of chronology. As mentioned before, Gildas makes it clear that he is writing while Ambrosius' grandchildren are extant, so we must look two generations before Gildas, so our question becomes when did Gildas write?

Dating Gildas' work De Excidio is a much fretted over task, and I have written on it before, but to summarize, there are a handful of clues that can get us in the right direction. The first is that Gildas makes no mention of the plague that swept Britain in the 540s

It would be highly unusual for him to not use this as an example of how God was castigating the wicked princes of Britain, So he was either writing much later or earlier than that. He also writes about the King of Gwynedd of his time, Maglocune (Maelgwn Gwenydd)

Maelgwn is said to have died of the Yellow Plague in 547, so Gildas was writing before that. Gildas tells us that Badon happened in the year of his birth forty-three years and one month ago. The Welsh annals give Badon's date at 516, extremely incongruous with this info

However, we must note that many early Annals were recorded only according to the Easter Cycle every 19 years. This gives us a little bit more wiggle room. This is where the Venerable Bede comes into our story. Bede lifts his portion on Badon almost verbatim from Gildas

The main difference is that Bede dates Badon as taking place forty-four years AFTER Saxon arrival in Britain. He gives us said date for the Arrival, 449, giving us a date of 493 for Badon. Considering this, then that gives us a date for Gildas of 536.

This is within our parameters quite easily, accounts for Maelgwn's experience, as well as the lack of plague, and taking note of the incongruity caused by the Easter cycle, the taking nineteen years from the Annals date of 497, Badon likely happened then.

This brings us again to Gildas words on Ambrosius' grandchildren, who are implied to be adults and likely of the same rough generation of Gildas. With a rough generational gap of 30 years this would place Ambrosius' birth in the mid 430's.

This places Ambrosius' perfectly to be the commander of the early British resistance around the mid 460s. A seasoned commander in his 40s, very possible, even considering that Vortigern's sons Vortimer and Catigern were said to have fought as generals under his command.

This would have made him one of the most senior commanders available for a battle in the 490s, in his 60s, easily possible, do if we assume is the victor of Badon and the Arthur mentioned in the Annals then it's likely Camlann also mentioning Arthur was his as well.

If we take the date for Camlann at face value this would make Ambrosius over 100 years old, or even with a more conservative estimate for his Birth almost 90. Even with the 19 year adjustment, he would still be close to 90. So it seems unlikelier and unlikelier that he was Arthur

Ambrosius may have even been present at Badon, and may have been the most seasoned commander there, but it would seem that a younger Prince named Arthur ultimately won the day for the British, possibly as the Annals implies, via a bold cavalry charge into the Saxons.

Ambrosius may have still contributed to the legends, as Geoffrey absorbs some of his narrative and places him as Arthur's uncle, and some elements may have still been conflated and projected onto Arthur, a major example that we will visit in part 2 of this later.

King Arthur in Film Part 1: King Arthur (2004)

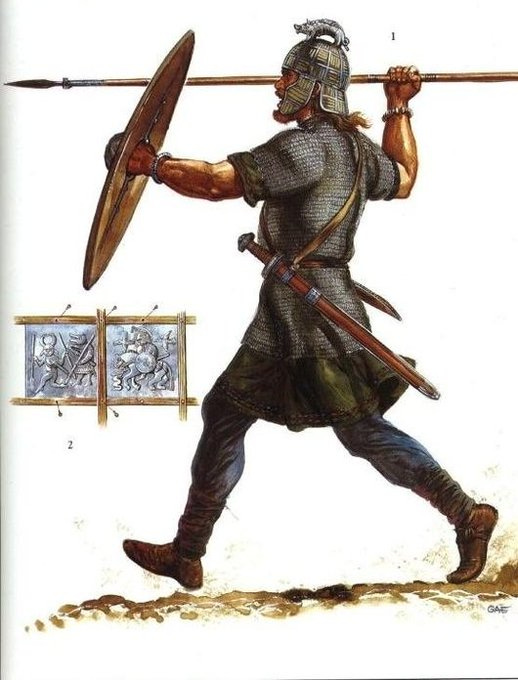

An ambitious, and often misunderstood vision of Arthur as a Roman commander of Sarmatian Cavalry stationed in Britain. Directed by Antoine Fuqua, and taking the approach of an Arthur more grounded in history than myth, draws much of it's ideas from the Sarmatian hypothesis.

For those unfamiliar with said hypothesis, there are parallels between elements of the Ossestian Nart Sagas and some of the later Arthurian tropes (many I have discussed previously, which you can find in the link in my bio)

The idea is, that a group of Sarmatians came with not only their way of war, but also cultural influences, seeding ideas that get wrapped around a Roman commander in the late 2nd early 3rd century named Lucius Artorius Castus.

Unfortunately, there is no evidence that Lucius ever commanded the Sarmatians stationed in Britain, and with the ranks he held it is even more unlikely that this is the case. Upon close inspection much of the Sarmatian theory is little more than wishful thinking.