My good friend p5ych0p0mp has once again graciously allowed me to post an article of his, this time touching on a new set of possible battle sites for Arthur’s battles as well as a semi-narrative exposition for said battles and campaign. This is a great one, so settle in and enjoy!

Where was King Arthur and his famous battles?

The earliest references to Arthur are found in material relating to the Hen Ogledd (Northern England & Southern Scotland). The most common example is the Bardic poem “Yr Gododdin” by Aneurin: “He fed black ravens on the rampart of a fortress. Though he was no Arthur” The Arthurian period is typically dated to the late 5th and early 6th century. In the later 6th century we see a rapid popularisation of the name Arthur attesting to the historicity of a prominent earlier figure. Arthrwys ap Mar is the only candidate that fits this chronology.

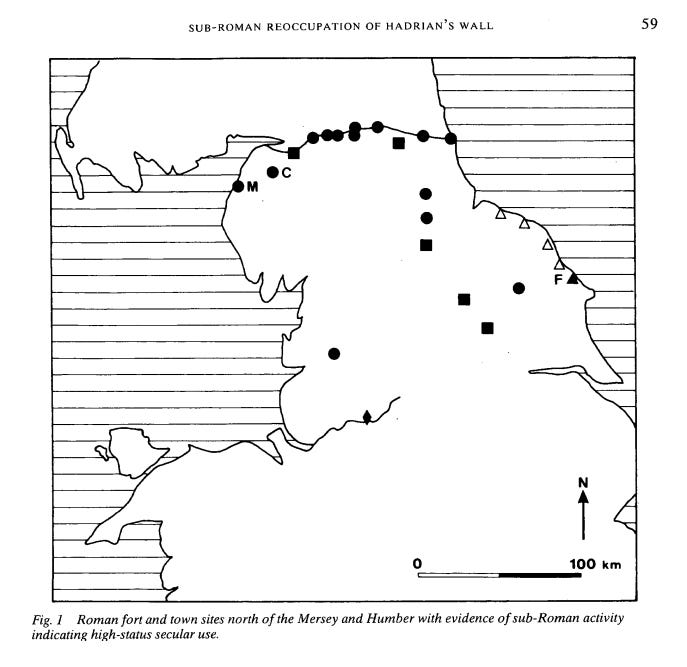

Arthrwys appears in the genealogies of Coel Hen, the founder of a Northern empire. Coel’s descendants ruled over Kingdoms such as Ebrauc (York), Rheged (Carlisle) and Elmet (Leeds). In Welsh tradition Peredur, and thus also his grandfather Arthrwys, is associated with Ebrauc. Post-Roman kingdoms commonly emerged from Roman and pre-Roman territories e.g. Votadini became Gododdin, Novantae became Nouant & Damnonii became Strathclyde. The core territories of the Coeling dynasty all fall within the boundaries of the Brigantes in Northern England. During the Roman period the highly militarised zone of the Brigantes was ruled by the “Dux Britanniarum” from Ebrauc. Kenneth Dark has demonstrated that the forts of the Dux were reoccupied and redeveloped in the post-Roman period by a group of powerful and high status Britons.

Most Roman forts were abandoned all over Britain but Dark observed "that out of at most 16 sites with later 5th-6th century evidence no fewer than 14 had probably been under the command of the Dux Britanniarum at the end of the 4th century". It was Coel Hen that founded and organised this new empire, especially around the northern frontier around Hadrian’s Wall. His epithet “Godebog” meaning “protector” illustrates his motivations. The intervallate Britons, Picts, Scots and later Angles posed a continual threat.

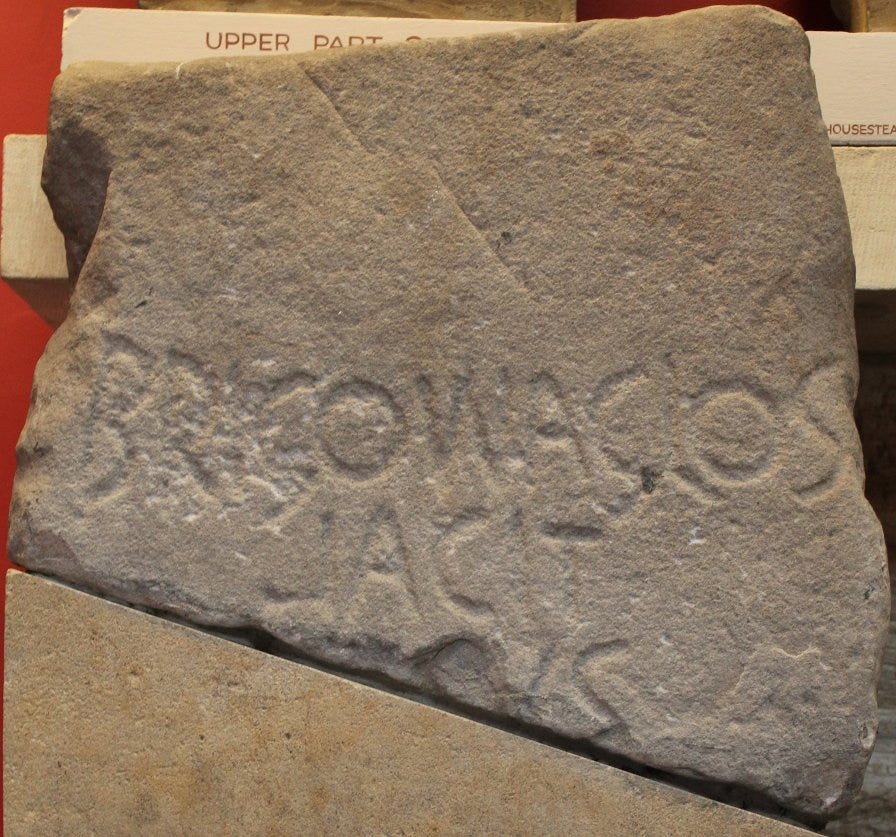

It is apparent that despite the existence of numerous petty kingdoms and over kingdoms within the territory of the Brigantes, there was a Coeling elite ruled by a single “supreme guledig” or High King. Arthrwys was one such “Prince of the Brigantes” (See Brigomaglos Stone).

Before we begin our survey of Arthur’s battle sites it is important to add context and understand who the traditional enemy of the Coeling and Arthur was. John Koch’s illuminating work on “Yr Gododdin” provides us with a quick summary. The Battle of Catraeth saw an alliance of Cynwydion Britons (Gododdin & Strathclyde) and their federate Angles of Bernicia raiding a stronghold of the Coeling. “The army of Gododdin and Bernicia (& Strathclyde)” “went down into Brigantia” where “they fought for land against the descendants of Godebog (Coel Hen)”.

A warrior characterised as “the avenger of Aeron” reveals the cassus belli for Catraeth. The Coeling, under Arthrwys and later Urien, had recently annexed the territories of Nouant (Galloway) and Aeron (Ayr). Clearly both factions were vying for control of the intervallate zone.

In Arthur’s time the ruler of Strathclyde was a Pictish conqueror warlord named Caw. He fathered the well known writer Gildas and the traditional enemy of Arthur named Hueil.

Gododdin was ruled by Cadleu ap Cadell (Father of King Lot). In later decades Gododdin was a client of Strathclyde and this may have been the case even at this time. “Picts” and “Saxons” colluding was also a recorded phenomena as far back as the “Great Conspiracy” in 367. It was probably Cadleu (and perhaps Caw) that originally invited the Angle mercenaries used by their descendants at Catraeth. The Angles were encouraged to settle the Gododdin territory called Bryneich (which later became Bernicia) in exchange for their military services.

The 9th century Historia Brittonum by Nennius contains the famous Chapter 56 that lists Arthur’s battles. It begins with an account of the legendary “Octa” “from the northern part of Britain”. It suggests Octa came to Kent in the South where the battles with Arthur occurred.

After detailing the battles (which we will see are actually all Northern) the chapter concludes with Arthur’s ultimate victory over the “Saxons” who ceased to be a threat until “the time in which Ida reigned, who was son of Eobba. He was the first king in Bernicia”.

This ending relating to a distinctly Northern King of Bernicia only makes sense in a Northern context and doesn’t logically follow the events allegedly in the South. Amongst other things this has prompted various historians such as Dumville, Hunter-Blair and Marsden to reassess. Earlier in the HB, Hengist states “I will send for my son and his brother... ...you can give them the countries in the north, near the wall called Gual... ...Octa and Ebusa arrived with forty ships.”

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle under the year 547 states “Ida began to reign, from whom arose the royal race of Northumbria… ...Ida was the son of Eoppa, Eoppa of Oesa”. The HB also gives this genealogy of Ida son of Eobba son of Ossa. Some detective work by the Arthur sceptic David Dumville uncovered a previously unknown entry in a manuscript that was found in Bern, France. “547 Ida begins to reign, who was son of Eoppa, son of Oesa. That Oessa first came to Britain.” This entry confirms that Ossa and Eobba were the first settlers of Bernicia. The obvious similarity in the names Ossa-Octa and Eobba-Ebissa has lead scholars such as Hunter-Blair to conclude that Nennius confused them in his Historia Brittonum.

The entries in HB that state Octa and Ebussa settled in the North near the Wall and fought Arthur should be correctly attributed to Ossa and Eobba. This neatly explains the relevance of the Arthur battle chapter ending in a reference to Ida (because he was son of Eobba). Therefore the events recounted in the Historia Brittonum actually depict Arthur winning a series of victories against Ossa and Eobba before Ida recovers Anglian prospects two generations later. Ida’s floruit of 547 puts Ossa’s floruit in the 490’s, the exact date of Badon.

Furthermore a separate Welsh tradition recorded in a confused entry of the “Bonedd y Sant” confirms exactly our conclusion. “Ida Great Knee... ...son of Ossa Great Knife, King of England, the warlike man who contended with Arthur at the battle of Badon.” Now we have confirmed that Arthur’s enemies Caw in Strathclyde and Ossa in Bernicia were also Northern we can examine the battles and locations associated with Arthur himself.

The first source we will analyse is an archaic early poem by Taliesin called “Cadeir Teyrnon” or “Chair of the Prince”. “Arthur the blessed” is the subject of the poem. He is said to be “from the stock of Aladur”. Inscriptions to a Romano-British War God “Mars Alator” reveal this to be a poetic theonym for Arthur’s warlike nature but perhaps also his descent from his father “Mar”.

The poem alludes to the idea that Arthur rose to prominence around “the old renowned boundary” which in the Hen Ogledd where Taliesin was active is almost definitely Hadrian’s Wall. “From the loricated Legion, Arose the Guledig (High King), Around the old renowned boundary.” Significantly the poem gives us a precise location and role for Arthur “Reon rechtur” which means “steward of Rheon”. It goes on to tell us Arthur launched raids on his enemy Caw of Strathclyde from this staging post.

”his red armour, and his host attacking over the rampart... ...He bore off from Cawrnur pale harnessed horses”.

In another Taliesin poem “Marwnat Uthyr Pen” Arthur and possibly his son Eleuther are described “with vigorous swordstroke against Cawrnur’s sons”. This confirms the traditional rivalry Arthur had with Caw and his son Hueil recorded elsewhere. More importantly if we can identify “Rheon” it can help us locate Arthur’s early battles. Luckily in this case there is a near scholarly consensus.

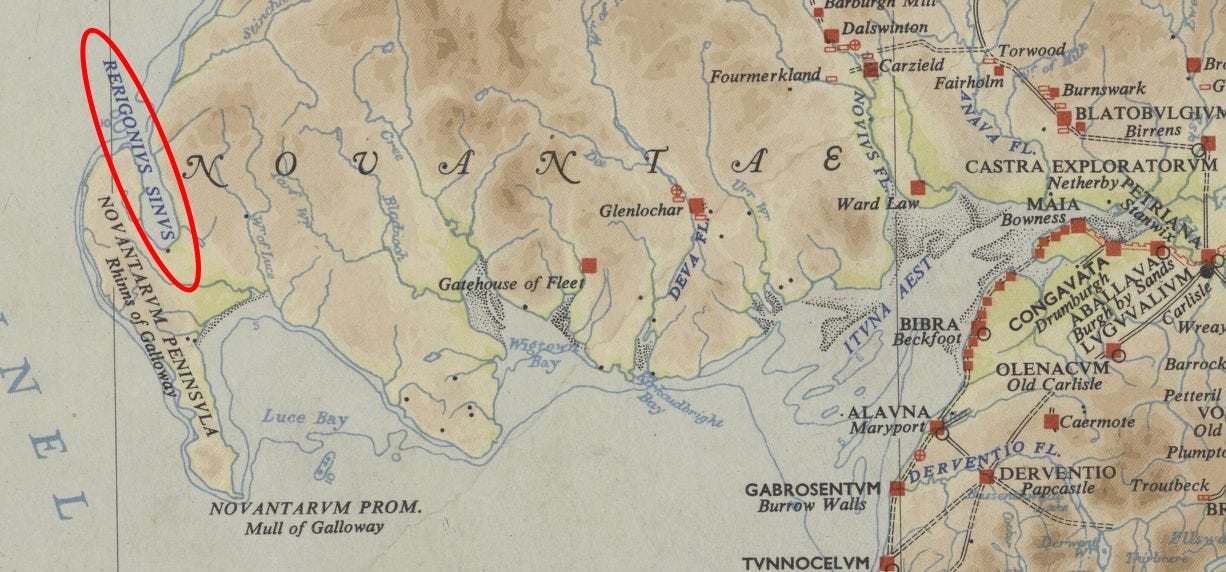

The triad entry “Arthur as Chief of Princes in Pen Rhionydd in the North” (Also spelled “Ryonyd” & “Rioned”) has been identified with “Rheon”. Watson first suggested “Ryonyd” could be further identified with Ptolemy’s “Rerigonion” (=> Rigon => Rion) meaning “Very royal place”.

“Rerigonion” was the tribal capital of the Novantae definitively located in the Rhinns of Galloway peninsula near Stranraer. Thus the location “Pen Ryoned” and “Reon” are also located there. The name “Ryonyd” is preserved in the modern place name “Loch Ryan”.

The exact location of the settlement within the Rhins of Galloway hasn’t been pinpointed but Robert Vaughan suggested the Mull of Galloway. The headland has extensive earthwork fortifications that make it the largest ancient enclosed site (and most southerly point) in Scotland.

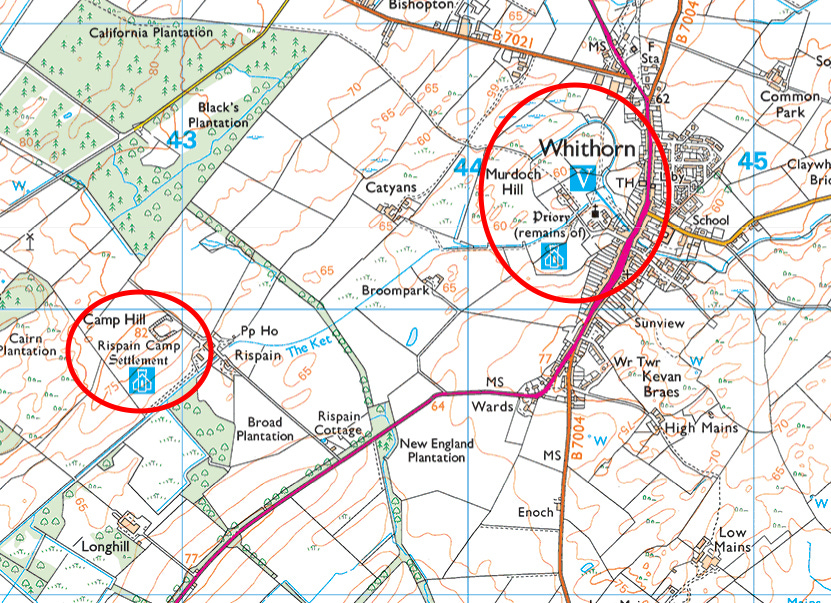

Why would Arthur be relegated to this peripheral edge you might ask? In the late 5th century and early 6th century the Coeling annexed this region known as Nouant which was previously ruled by Strathclyde. The missionary Saint Ninian set up his monastery near “Reon” at Whithorn.

@ActualAurochs has uncovered a vital piece of the puzzle hidden in the notoriously unreliable work of Geoffrey of Monmouth. A section of Geoffrey’s embellished and confused historia discusses figures named “Morvidus”, “Gorbonian”, “Arthgallo”, “Elidure” and “Peredur”.

Transparently these names correspond to the historically attested Kings of Ebrauc: Mar (Arthur’s father), Garbanian (Arthur’s grand uncle), Arthrwys (Arthur), Eleuther (Arthur’s son) and Peredur (Arthur’s grandson). As @ActualAurochs has demonstrated, it is likely Geoffrey derived these passages by expanding a brief Northern Annal now lost to us. Geoffrey’s narrative indicates that Mar died when Arthrwys was young and so his senior grand uncle Garbanian ruled in his place as regent.

Geoffrey also includes some locations which have the ring of truth about them. Whilst Garbanian ruled, a young Arthrwys was wandering in the Forest of Calaterium (Celidon) somewhere near Alt Clut (Strathclyde). When Garbanian died, Arthrwys returned to York to be crowned. A separate genealogical tradition records an “Arthrwys ap Garmon (Garbanian)”. This corruption (Arthrwys is son of Mar not Garbanian) has a common ancestor with Geoffrey’s narrative which is probably the same lost northern annal showing Arthrwys ruled after his great uncle.

The Historia Brittonum Chapter 56 listing Arthur’s battles implies that Arthur was not the most senior royal but was appointed as “Dux Bellorum” meaning “Duke of Battles”. From all this information we can synthesise a probable chronology for Arthur’s early career. Garbanian appoints a young Arthur as “Duke of Battles” and sends him to “the old renowned boundary” and northern frontier of Hadrian’s Wall. He is also appointed as the steward of the newly acquired Coeling territory of Nouant.

Arthur is tasked with protecting the sanctuary of Ninian and repelling Caw as well as the other opponents of the Coeling. Shortly after his campaigning within the forest of Calatarium (Celidon) he returns to York to be crowned King after Garbanian’s death. Most scholars agree that the battle list recorded in the HB is based on an older bardic source as it retains a rhyming scheme. This lends credibility to the authenticity of the list as this kind of battle list poem was commonly produced for other notable leaders of the period.

The HB battle list chapter implies all of Arthur’s battles were against “Saxons” but this is unlikely. The original northern battle poem likely referred to a range of enemies including Ossa, Caw and others. For the sake of brevity I will only state my preferred battle locations.

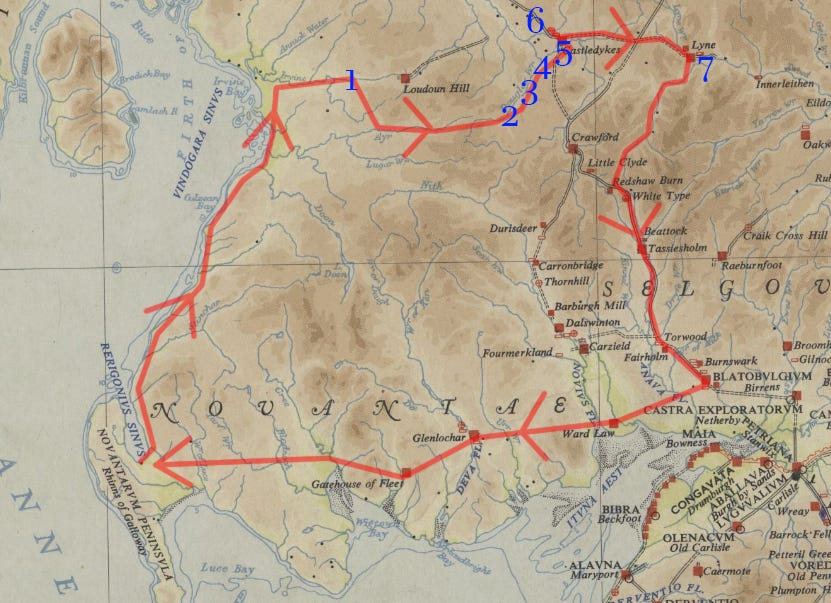

“His first battle was at the mouth of the river which is called Glein”. The River Glen in Northumberland at the foot of early site of Angle settlement (Yeavering Bell Hill Fort) and close to a mainline Roman road is an attractive option but I favour another location. We know Arthur was probably based in the West around Loch Ryan in his early career as “Reon rechtur” and “Dux Bellorum” where he saw conflict with Caw. Between “Reon” and Caw in Strathclyde sits another river called the “Glen Water” also on a Roman road.

The Glen Water flows into the Irvine at Darvel within the contested territory of “Aeron” (later annexed by the Coeling). This location suits a raid by a young Arthur to “bore off from Cawrnur pale harnessed horses”. It also fits better geographically with the next battles.

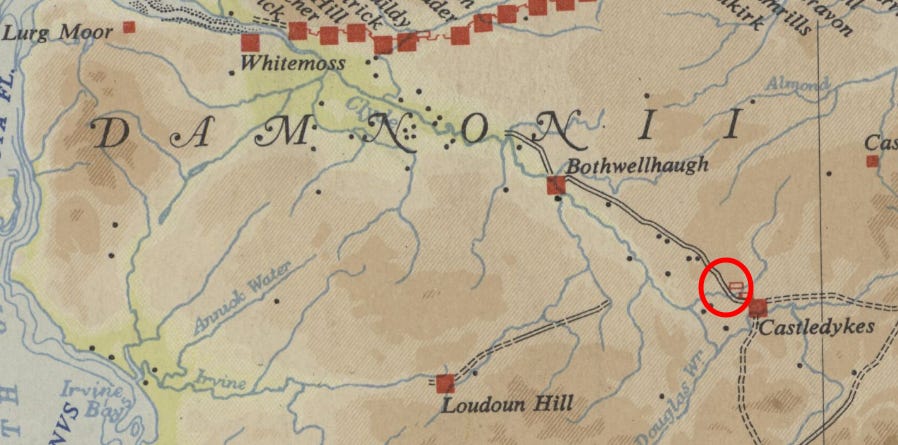

“His second, third, fourth, and fifth battles were above another river which is called Dubglas and is in the region of Linnuis”. Kenneth Jackson, in an article in Modern Philology, determined that Linnuis derives from Lindenses, meaning “the people of Lindum”. This has been assumed by most to refer to Lincoln which was recorded as “Lindum” by Ptolemy. Unfortunately however there is no River “Dubglas” near Lincoln which would be rendered as “Douglas” in a modern place name. Fortunately Ptolemy does list a second “Lindum” within the territory of the Damnoni (Strathclyde). The inaccuracy of Ptolemy, especially within Scotland, means that this “Lindum” (Linnuis) hasn’t been conclusively identified.

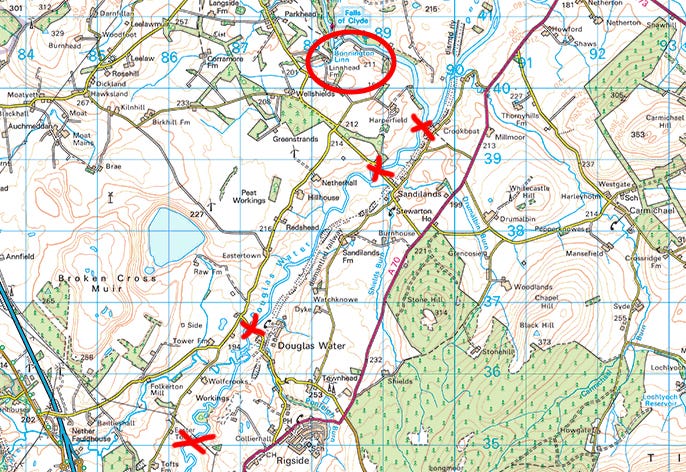

There is however a River Douglas (Dubglas) that runs within the boundaries of the same Kingdom. This river Dubglas lies only a short distance to the East from the site of our first battle at the mouth of the River Glein.

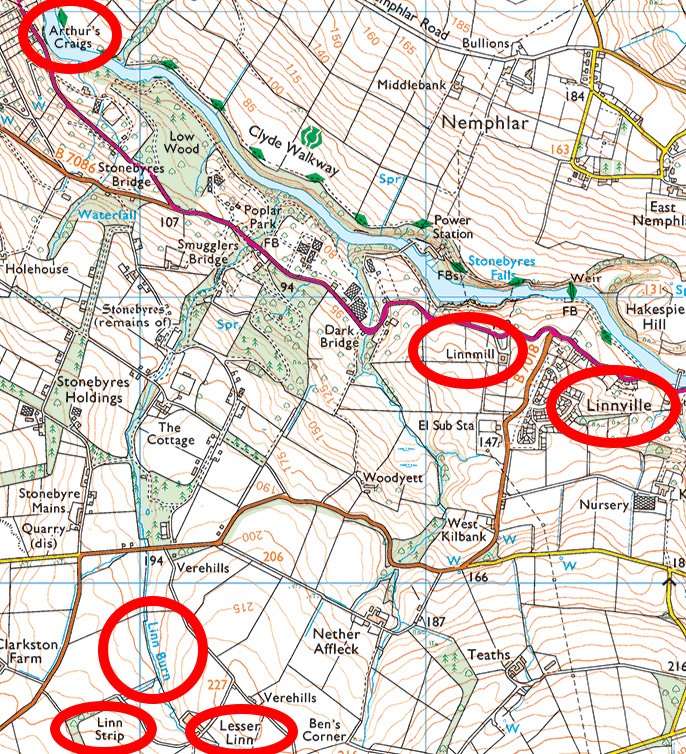

There was a series of intense battles at shallow fording points, Arthur’s forces probed the defences of Strathclyde. Where the River Douglas flows into the River Clyde near Lanark there is a series of “Linn-” place names which may account for our “Lindum” and “Linnuis”.

Linnhead, Linnville, Linn Mill, Linn Burn, Lesser Linn, Linnside all occur in a small area. These names derive from the nearby famous Falls of Clyde which is a series of waterfalls called Bonnington Linn, Corra Linn, Dundaff Linn, Stonebyres Linn.

“Linn-” is a Brythonic place name element that means “Pool of Water”. It is apparent that this region could easily have been referred to as “Linnuis” meaning “People of the Waterfalls” which would be an apt name for the Strathclyders near the Falls of Clyde and River Dubglas.

The next two battles listed by Nennius are the most difficult and the most straightforward to identify. To aid identification of the tricky 6th battle we shall first look at the easier 7th battle. “The seventh battle was in the forest of Celidon, that is Cat Coit Celidon.” There is little doubt amongst scholars that “Celidon” refers to an area North of Hadrian’s Wall in what was once dubbed “Caledonia” by the Romans. The term “Caledonia” originally referred to just the highlands of Scotland but later saw more general use for Scotland as a whole.

However in the traditions of the Hen Ogledd it came to refer to a more specific location. The early Welsh poetry of Myrddin Llallogan (Merlin) retells the story of the bard that became a prophetic madman after witnessing slaughter at the Battle of Arfderydd (Arthuret).

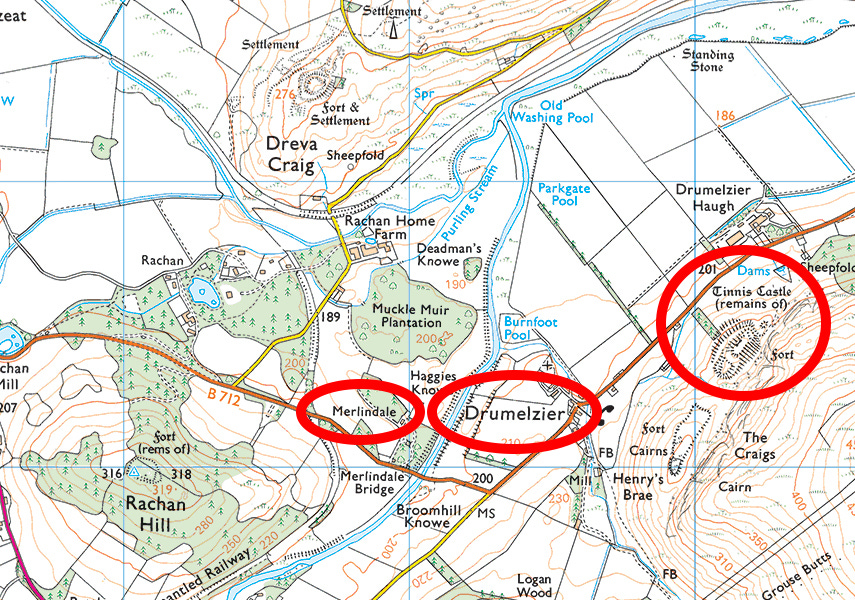

After the battle Myrddin fled to “Coed Celyddon” to be hunted by Rhydderch Hael the King of Strathclyde. With only woodland creatures for companionship Myrddin wandered Celyddon lamenting his cursed fate. Myrddin was captured by a King Meldred who kept him in chains at Castellum Dunmeller to extract prophecies. “Castellum Dunmeller” is the modern Tinnis Castle Hillfort above Drumelzier. Myrddin prophesized his own triple death “Pierced by a stake, suffering stone and wave”.

Killed by King Meldred’s shepherds, Myrddin was buried “at the junction of the Powsail with the Tweed”. The tales that associate Myrddin with Tweeddale tell us this valley was possibly considered synonymous with “Coed Celyddon” or the “Forest of Celidon”.

Even in death Myrddin’s prophecies continued. Another local wizard named “Thomas the Rhymer”, whom we shall return to later, supposedly foretold the union of the crowns “When Tweed and Powsail meet at Merlin's grave, Scotland and England that day ae king shall have”. Confirmation of identifying Tweeddale with Celidon can be found in the 15th century work of Scottish Historian Hector Boece commenting on the source of the river Clyde “risis out of the samin montane within the wood of Calidone”. To this day the source of the River Clyde and Tweed both emanate from within the same forest. This is confirmation that upper Tweeddale was also considered Celidon. A third confirmation comes in the form of place name evidence.

In lower Tweeddale near Galashiels the “Caddon Water” flows into the Tweed near “Caddonfoot” and “Caddonlee”. These were recorded as “Keledenlee” in 1175 and “Keledene” in 1296. This “Keleden” almost definitely derives from “Celidon”.

The name element also occurs at “Caddon Bank” in middle Tweeddale. It seems therefore that the ancient name “Celidon” was considered the entire Tweed Valley in Arthur’s time. We will return to the exact battle site after establishing the site of Arthur’s difficult 6th battle.

“The sixth battle was above the river which is called Bassas”. This battle has long vexed scholars as there exists no compelling candidate anywhere in Britain, this has lead many to conclude it is impossible to locatable. But if we assess the geography of our located battles we see that they exist on a linear East-West axis suggesting the first seven battles were a part of the same campaign. This raises the possibility that the river “Bassas” exists on this axis between Dubglas and Celidon.

Andrew Breeze notes there is few known credible Brythonic “Bassas” hydronyms and suggests this may be due to a simple scribal copying error. The only known form that resembles “Bassas” whilst satisfying the underlying poems rhyming scheme is “Tarras” meaning “powerful”. Breeze goes on to note the ease at which such a copying error could be made, the characters “t”-“b” and “r”-”s” in insular script are “strikingly similar” and so easily misinterpreted. In 1172 Carstairs near Lanark was recorded as “Castel Tarras”. This “Castel Tarras” sits on an important river crossing on a Roman road that blocks access to the heart of the Kingdom of Strathclyde. It sits roughly on the axis between Dubglas and Celidon and is therefore a strong candidate for the location of Arthur’s sixth battle.

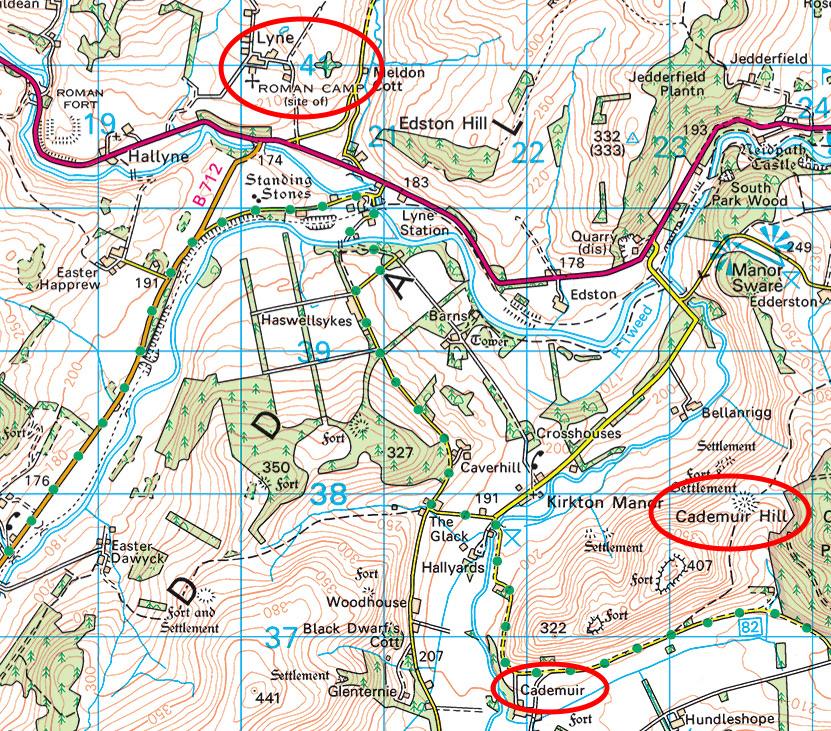

The obvious route from “Castel Tarras” for Arthur’s westwards campaign to proceed to Celidon (Tweed Valley) is following the Roman road to the Lyne Roman Fort near Peebles where the River Lyne flows into the Tweed. This is the probable site for Arthur’s 7th battle.

There are two significant toponyms that also indicate this was the Celidon battle site. A hill fort overlooks this section of the Tweed Valley called “Cademuir” which means “Battle Moor”. At the foot of “Cademuir” is “Arter Brae”, which possibly remembers Arthur himself.

This point in the Tweed Valley is a point of natural convergence if a combined force from Gododdin and Bernicia (Cadleu and Ossa) were mustering to meet a threat from the West. This marks Arthur’s first conflict with the “Saxons” but the last battle of this first campaign.

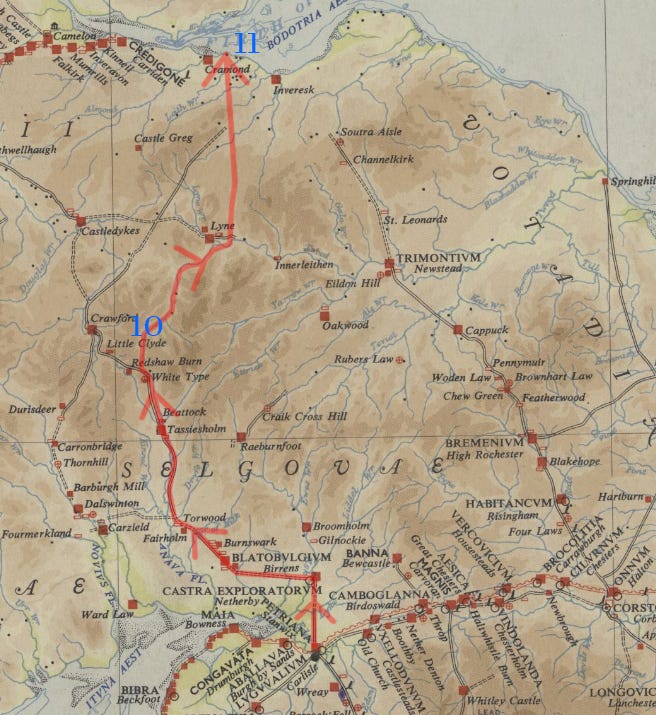

I believe these first seven battles were all in a single campaign by a young Arthur testing his enemies defences. A short march up the coast from “Reon” to “Glein” he first met Caw’s forces. Feigning a retreat Arthur dropped back slightly southwards to the Aeron valley. At the head of the Aeron Valley Arthur joined the source of the River “Dubglas” where downstream near the Falls of Clyde (Linnuis) Caw’s forces again pursued Arthur and clashed at four fords.

Abandoning all subtlety Arthur made for the main road into Strathclyde where he punched through Caw’s defences at Tarras. Satisfied with his raid on Caw, he continued marching west where he met a new threat for the first time in the form of “Saxon” federates of Gododdin. The battle in the Forest of “Celidon” was a fierce contest against a new and unfamiliar enemy which is why it was remembered in the lost northern annal. After this battle Arthur returned to his post at “Reon” to celebrate a successful campaign with his newly acquired plunder.

Arthur’s enemies were perturbed by his audacious campaign into their territories and so they hatched a revenge plot.

“The eighth battle was at the fortress of Guinnion, in which Arthur carried the image of holy Mary ever virgin on his shoulders and the pagans were put to flight on that day. And through the power of our Lord Jesus Christ and through the power of the blessed Virgin Mary his mother there was great slaughter among them.”

Andrew Breeze once again provides a solution to the place name “Guinnion”. The name of Coeling missionary “Ninian” in its original form is “Uinnian” or “Gwynion”. We already know that part of Arthur’s duty as “Reon rechtur” was sheltering the sanctuary of Ninian at Whithorn. This also neatly explains the overtly religious nature of the description. The “pagans” could refer to any of Arthur’s northern rivals who were all superficially Christian at most or explicitly Pagan. Caw the Pict is a likely candidate for this revenge raid. There is no surviving “Guinnion” place name near Whithorn, however very nearby is the interesting fortification known as “Rispain Camp” (From “Rhwospen” = “chief of the cultivated country”). I believe this could be Ninian’s Fort and the 8th battle site.

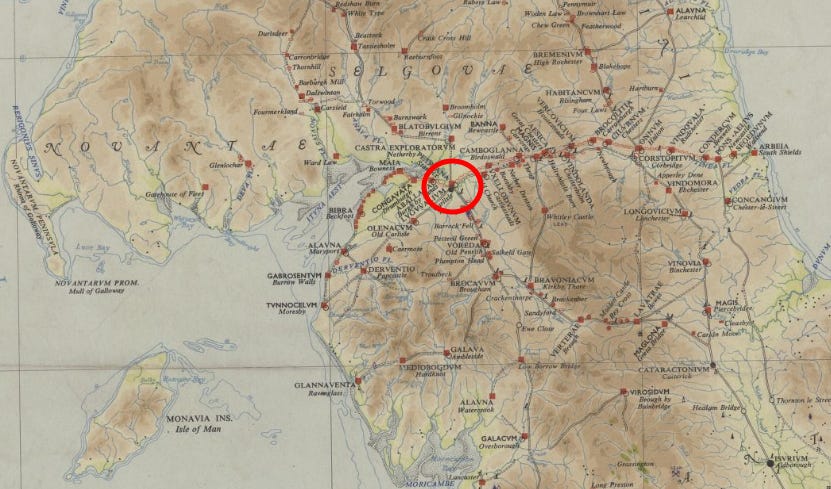

The ninth battle was a significant turning point for Arthur and may have been part of the same retaliatory strike against him as “Guinnion”, but this time occurring in the east and conducted by the formidable new opponent “Ossa” in collaboration with Gododdin. “The ninth battle was waged in the City of the Legion”. There were three legionary fortresses in Britain: York, Chester and Caerleon-upon-Usk. To determine which of these three we must examine the Latin used by Nennius. In one manuscript “urbe Legionis” (City of the Legion). In another manuscript with an additional “quae bryttanicae Cair Lion dicitur” meaning “which in Brittonic is called Caer Lion”.

Gildas also mentions an “urbs Legionum” lamenting the inaccessibility or destruction of saintly shrines “whose places of burial and of martyrdom, had they not for our manifold crimes been interfered with and destroyed by the barbarians” Field made a strong case that of the three possibilities only York fits the language of Gildas. The term “urbs” is only applicable to major administrative cities, the second term “Legionum” is a plural for multiple legions. Both of these can only be York. As well as being known as Ebrauc, York was also known as Urbs Legionis and Caer Leon meaning “City of the Legion” in Latin and Brythonic respectively. We already know that after the campaign in Celidon Arthur returns to the Coeling capital of York upon Garbanian’s death.

Ossa commanded a fleet of forty ships manned by experienced sea raiders. As a part of the retaliation for Arthur’s raid I believe Gododdin-Bernicia simply sailed around Hadrian’s Wall and sacked York, destroying the shrines mentioned by Gildas and killing High King Garbanian. After hearing the devastation inflicted upon Caer Leon Arthur marched back to the city and liberated it from the “Saxons” who fled back North. Interestingly Geoffrey of Monmouth even devotes an entire chapter to Arthur rebuilding York especially its devastated sacred shrines.

“On entering the city, he beheld with grief the desolation of the churches... ...which were half burned down, had no longer divine service performed in them: so much had the impious rage of the pagans prevailed.”

“The churches that lay level with the ground, he rebuilt.. ...Also the nobility that were driven out by the disturbances of the Saxons, he restored to their country.”

As Ken Dark notes, all that is known archaeologically about the “Anglian Tower” in York is that it is post-Roman and pre-9th century. It is a real (if speculative) possibility this was part of Arthur’s re-fortification after the Battle of Urbes Legionis.

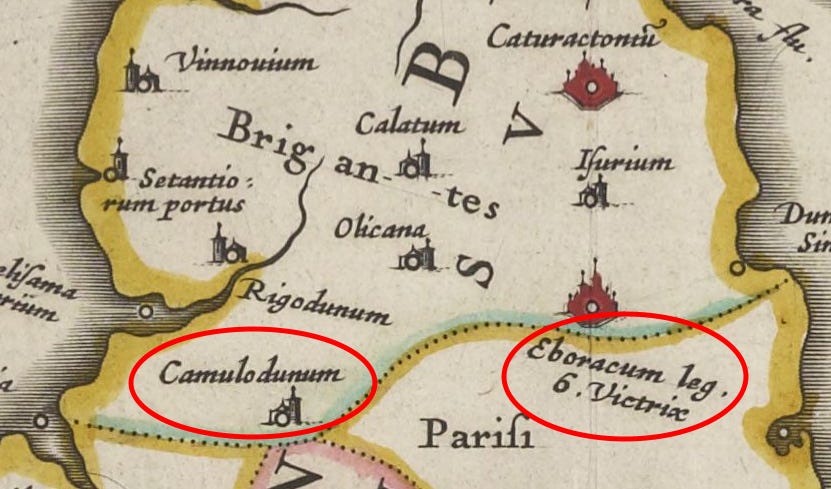

If York was known as “Urbes Legionis” in Latin and thus “Caer Leon” in Brythonic, as I believe it was, this may explain the later association between Arthur and Caerleon-upon-Usk in Geoffrey of Monmouth and the early romances. This is an understandable confusion. The early French romanticist Chretian de Troyes also strongly held “Caer Leon” to be a court of Arthur. Chretian was also the first writer to mention “Camelot” in his work “Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart”.

“Upon a certain Ascension Day King Arthur had come from Caerleon, and had held a very magnificent court at Camelot as was fitting on such a day.” Chretian’s sources are unknown, possibly Breton folk tradition, but even here there may be some truth.

Ptolemy listed a “Camulodunum” among the settlements of the Brigantes somewhere near Ebrauc. Called “Campodunum” in other sources and located in various places but it hasn’t yet been solidly identified.

After the Anglian King Edwin absorbed Ebrauc and Elmet (with the blessing of the Coeling Rhun ap Urien) Bede notes “he built a church in Campodonum” “in the Country called Loidis” “which is in Elmet wood”. One possibly location of this Camulodunum is Barwick-in-Elmet Hill Fort near Loidis (Leeds). It was potentially the capital of Elmet and held by a proto-Lancelot (Arthrwys’ brother Llenneac):

https://twitter.com/ActualAurochs/status/1634730356854095874

Chretian mentions another court in “Yvain, the Knight of the Lion”. “Arthur, the good King of Britain... ...held a rich and royal court upon that precious feast-day... ...The court was at Carduel”. Most scholars identify this with Carlisle, the seat of Rheged and Owain ap Urien.

Chretian has correctly identified the three main seats of the Coeling even correctly associating them with the right persons. Arthrwys at Caer Leon i.e. modern York, Llenneac at Camulodunum i.e. modern Leodis and Owain at Carduel i.e. modern Carlisle.

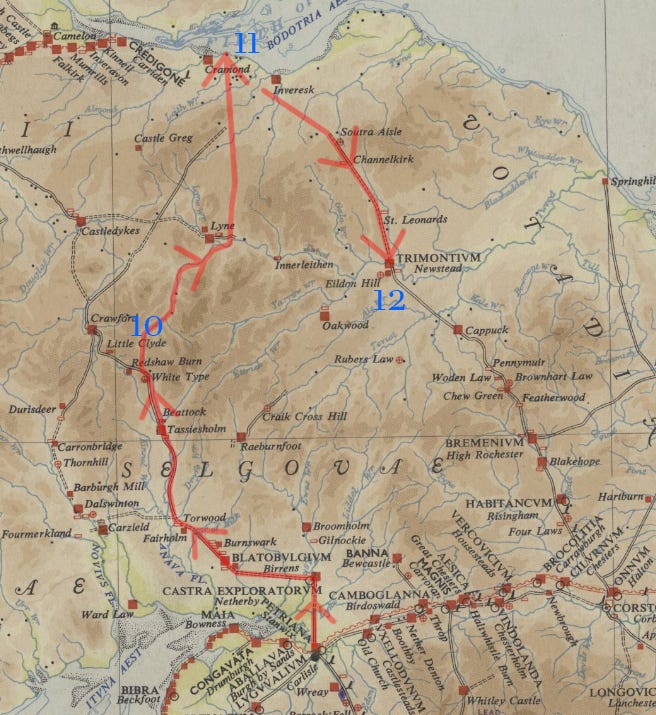

Returning to our quest to seek Arthur’s battle sites, after the Battle of Urbes Legionis Arthur was now High King of the Coeling and intent on putting down this existential threat that was able to strike at the heart of his territory. The main threat in Arthur’s mind was the “Saxons” lead by Ossa and their British masters in Gododdin. “The tenth battle was waged on the banks of a river which is called Tribruit.” This battle is significant as it is the only one (except Badon) corroborated by another source. The pre-Galfridian poem “Pa Gur” depicts Arthur and his warriors engaged in a series of battles including at “Tryfruid” which is another form of “Tribruit”. The poem goes on “In Mynyd Eiddyn, He contended with Cynvyn” which leads us to our next battle listed in the HB.

“The eleventh battle was fought on the mountain which is called Agned.” John of Fordun in the 14th century “Chronica Gentis Scotorum” and William Camden in the 17th century both write that “Agned” was an alternative name used for “Mynyd Eiddyn” (Edinburgh). The link in “Pa Gur” between a battle at “Tryfruid” occurring before a battle at “Mynyd Eiddyn” seems to confirm the Agned of Nennius is “Mynyd Eiddyn”. Arthur’s opponents at Edinburgh are called “Cynvyn” meaning “Dog Heads”.

The meaning of this insult hasn't been entirely deciphered but it is clearly some kind of northern cultural motif now lost to us as this Pictish carving of a dog headed warrior suggests. The tenth, eleventh and twelth battles of Arthur were a retaliation against Gododdin-Bernicia for the strike on York. “Mynyd Eiddyn” was the main seat of Gododdin hence why it was a target. It is therefore likely “Tryfruid” exists somewhere between Hadrian’s Wall and Edinburgh.

“Pa Gur” states the battle at “Tryfruid” was against “Gwrgi Garwlwyd” which translates as “Rough Grey Man Hound”. This is probably the commander of the “Dog Heads” of Edinburgh attempting to intercept Arthur “on the borders of Eidyn” before he reached their heartland. A “Tryfruid” is also mentioned in Myrddin’s poetry. As we know Myrddin wandered in Celidon, which we know was the Tweed Valley, then perhaps “Tryfruid” is to be found here too. A suitable location for a battle between Arthur and Gododdin.

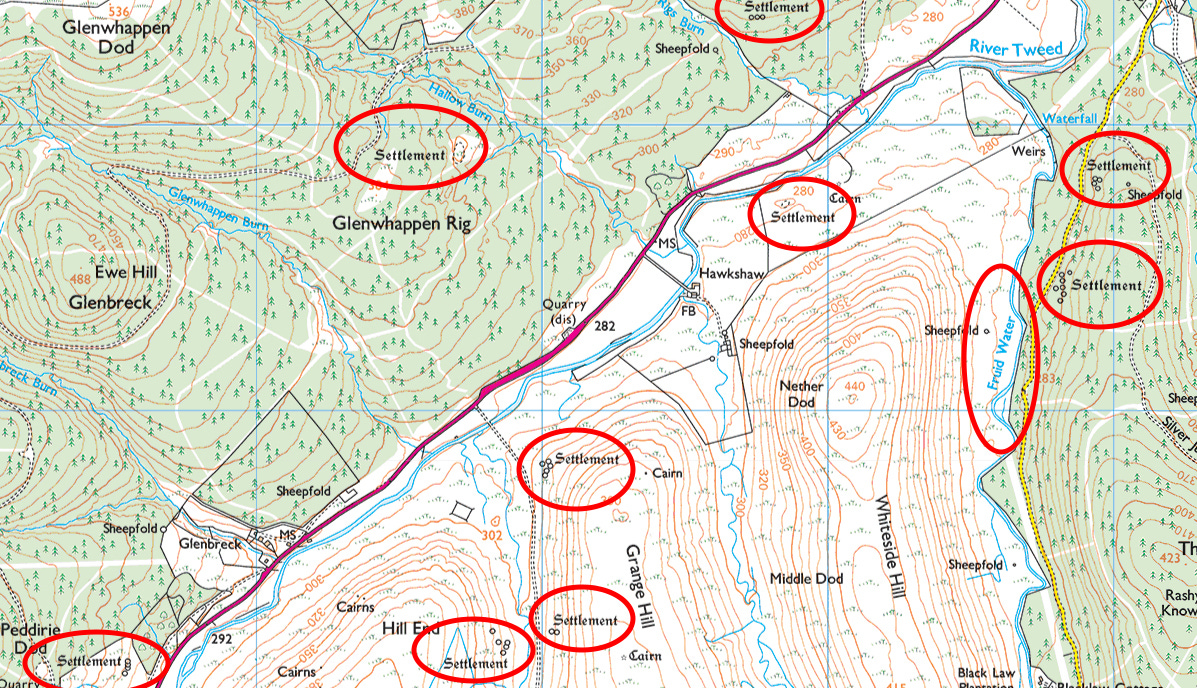

There is no river named “Tryfruid” but there is a river in upper Tweeddale called the “Fruid” water. The first element can be accounted for as perhaps “Tref” meaning settlement (Trefruid = Settlement of Fruid). The Ordnance Survey map confirms the presence of early settlement.

The presence of multiple ancient “Enclosed Cremation Cemeteries” where the Fruid joins the Tweed are appropriate monuments for a possible battle site but unfortunately these seem to date to the Bronze Age.

We can therefore conclude Arthur marched his host up the western Roman road where he joined the Tweed Valley sweeping aside Gwrgi Garwlwyd at the settlement of Fruid before continuing on to Edinburgh to exact his revenge upon the architects of his uncles death.

The ruler of Gododdin, Cadleu ap Cadell, was probably slain by Arthur leading to the ascension of his son Letan who went on become the King Lot of Arthurian romance. It was the sons of Letan (and Caw) that lead the force against Arthur in his final battle of Camlann. After dealing with Gododdin Arthur turned his sights upon their “Saxon” allies in Bernicia who conducted the attack on York. As recalled in the “Bonedd y Sant”, “Ossa Great Knife, King of England, the warlike man who contended with Arthur at the battle of Badon.”

Nennius says “The twelfth battle was on Mount Badon in which there fell in one day 960 men from one charge by Arthur; and no one struck them down except Arthur himself, and in all the wars he emerged as victor.” Gildas only comments briefly with “the siege of the Badonic hill”. If Nennius is correct that the “Saxons” “arrived with forty ships” in Bernicia then a rough estimate of 25 warriors per ship would give a total of 1000. This number correlates well with the 960 killed at Badon which sounds like it was a merciless slaughter if true. The use of the word “siege” by Gildas has prompted scholars to seek a hill fort called Mynydd Badon. An Irish source recounting the life of Saint Uinnian suggests Ninian was present at the battle:

“Once upon a time Saxons came to ravage the Britons… ...They pitched camp on the side of a lofty mountain. The Britons betook themselves to Uinnian to ask for a truce... ...The Saxons gave him a refusal. Uinnian gave a blow of his staff on the mountain, so that the mountain fell on the Saxons, and not a man of them escaped to tell the tale.”

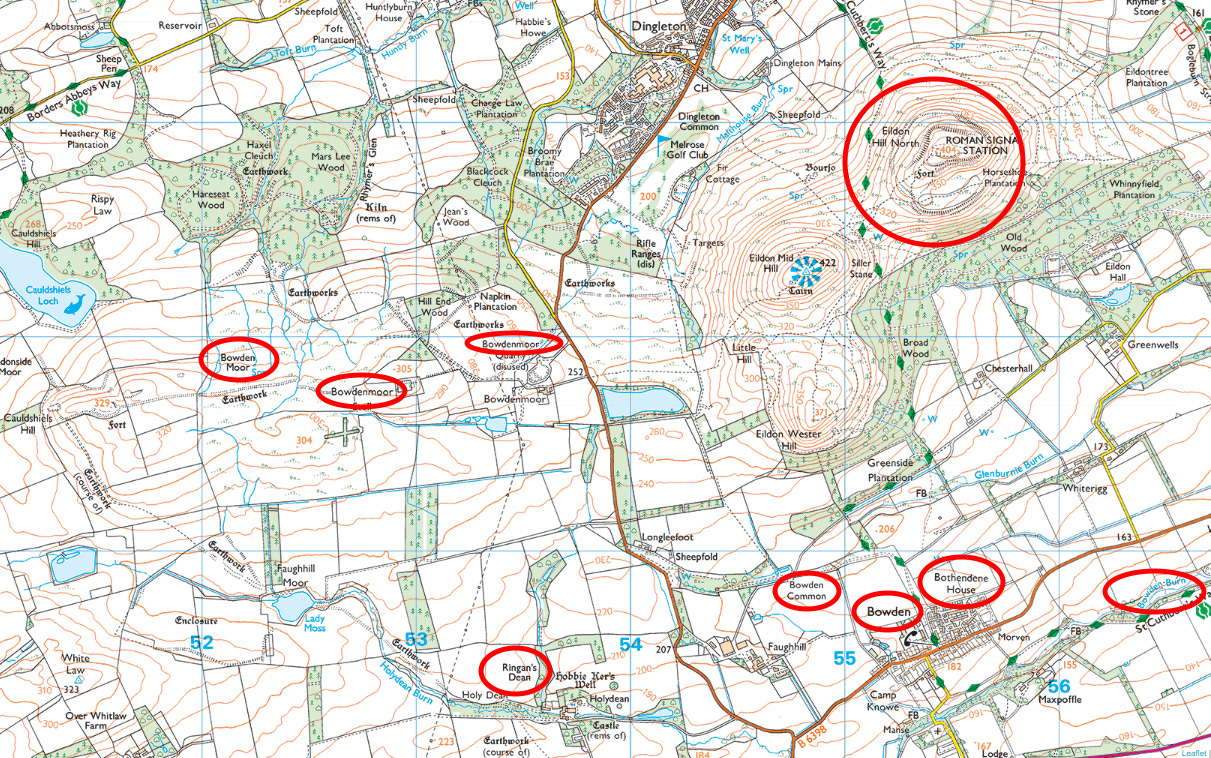

Summarising this information we are looking for a hill fort large enough to house approximately one thousand of Ossa’s “Saxons”. It is called something like “Badon” and is located in or around the region of Gododdin settled by Ossa then known as Bryneich (Bernicia). There is a location that fits this description. It also has a folkloric connection with Arthur and was even settled as a buffer state by the descendants of the historical Arthrwys. Sitting within Celidon in the lower Tweed Valley at Melrose is the three Eildon Hills. It was called “Trimontium” or “Three Mountains” by the Romans. “Eildon” itself may be from the English “æled” + “dun” meaning “Fire Hill”, a suitable name for the site of a siege.

On the most northern hill sits what has been called the largest hill fort in Scotland. This is more than large enough to house one thousand “Saxon” warriors. At the foot of the Eildon Hills is a cluster of relevant place names which may preserve the Brythonic name of the area.

Etched with ancient earthworks Bowden Moor and Bowden Common sit above Bowden Village and Bowden Burn. On first glance “Bowden” seems distant from the historical “Badon”. However the earliest recorded form of the name in a charter of 1124 is “Bothen”.

The occurrence of “Ringan’s Dene” on Bowden Moor is significant too as “Ringan” is an alternative pet name given to Uinnian, as we have previously mentioned, he may have been present as an arbitrator at Mount Badon. “Bothen” is comprised of two Brythonic place name elements. As Alan James says, the Brythonic “Bod-” meaning “dwelling” is rendered “Both-” by English and Gaelic speakers. Possibly used interchangeably with “Bad-” amongst Brythonic speakers. The second element “-en” simply denotes “place of”. Thus the place name “Bowden” is from “Bothen” and “Boden” (and perhaps “Badon”) meaning “Place of Dwelling”.

Alan James gives examples of similar place names in Southern Scotland such as “Badentree Hill” and “Badenhay” also in Tweeddale as well as “Baddinasgill”, “Boden” and “Bothan” elsewhere. In some Welsh sources such as the “The Dream of Rhonabwy” Badon is called “Caer Faddon”. In the earliest maps of the “Bothen” area we can see a place named “Fadonsyd” (Fadon Side). This “Fadon” place name element beside “Bothen Moor” is perhaps another relevant toponym.

Sir Walter Scott relates “a fine legend of superstition”. The tale retells the story of a horse dealer named Canonbie Dick “One moonlight night, as he rode over Bowden Moor, on the west side of the Eildon Hills” he was approached by a mysterious figure. “He met a man of venerable appearance and singularly antique dress, who, to his great surprise, asked the price of his horses”. The identity of the mysterious man is eventually revealed.

“Thomas.. ..the Rhymer... ...to whom some of the adventures which the British bards assigned to Merlin Caledonius, or the Wild, have been transferred by tradition, was, as is well known, a magician, as well as a poet and prophet. He is alleged still to live in the land of Faery”

Canonbie was invited by Thomas the Rhymer inside a magical passageway that lead under the Eildon Hills. Inside the mountain he saw a large group of sleeping knights with Arthur their leader. Canonbie was then instructed to choose either the sword or the horn that lay before him. If he chose correctly he would be anointed “King of all Britain”. Not wanting to appear too aggressive Canonbie meekly chose the horn. A voice boomed "Woe to the coward, that ever he was born, Who did not draw the sword before he blew the horn!" Canonbie was ejected back onto Bowden Moor by a swift gust of wind where he died shortly after telling his story to a local shepherd. Choosing the sword is undoubtedly a good piece of wisdom to keep in mind next time you are taken to Faeryland by a wizard. While this kind of folklore about Arthur sleeping under the mountain is far from unique to Eildon it indicates Arthur had a real historic connection to the area. A more concrete historical link may be found in the Welsh genealogies.

A “Cadrod of Calchfynydd” is recorded as a descendent of Arthrwys. Skene and others have made the strong case that “Calchfynydd” can be identified as a 6th century kingdom in the Kelso-Eildon area. Kelso was recorded as “Calchou” in a charter of 1128. As an interesting side note King Charles III is a direct descendant of Arthrwys ap Mar via Cadrod Calchfynydd:

https://twitter.com/p5ych0p0mp/status/1654122255583178760

Aurochs has previously made the case that Calchfynydd was a buffer state set up by Arthur manned by his descendants to protect the Coeling heartlands from Gododdin and Bernicia. This buffer state may have been established in the wake of the Battle of Badon. After Badon for roughly 40 years there was a period of relative peace. This is sometimes known as “Pax Arthuriana”. It is unlikely there was no conflict with the other northern powers, for example with Tristan ap Tallwch.

https://twitter.com/p5ych0p0mp/status/1737494344477626636

It can certainly be said that according to Nennius and other sources that the “Saxons” didn’t recover their strength until Ida of Bernicia some two generations later. After a long reign Arthur finally met his end at the Battle of Camlann. I will not rehash the circumstances surrounding Arthur’s death which you can read here:

https://twitter.com/ActualAurochs/status/1738675587240120797

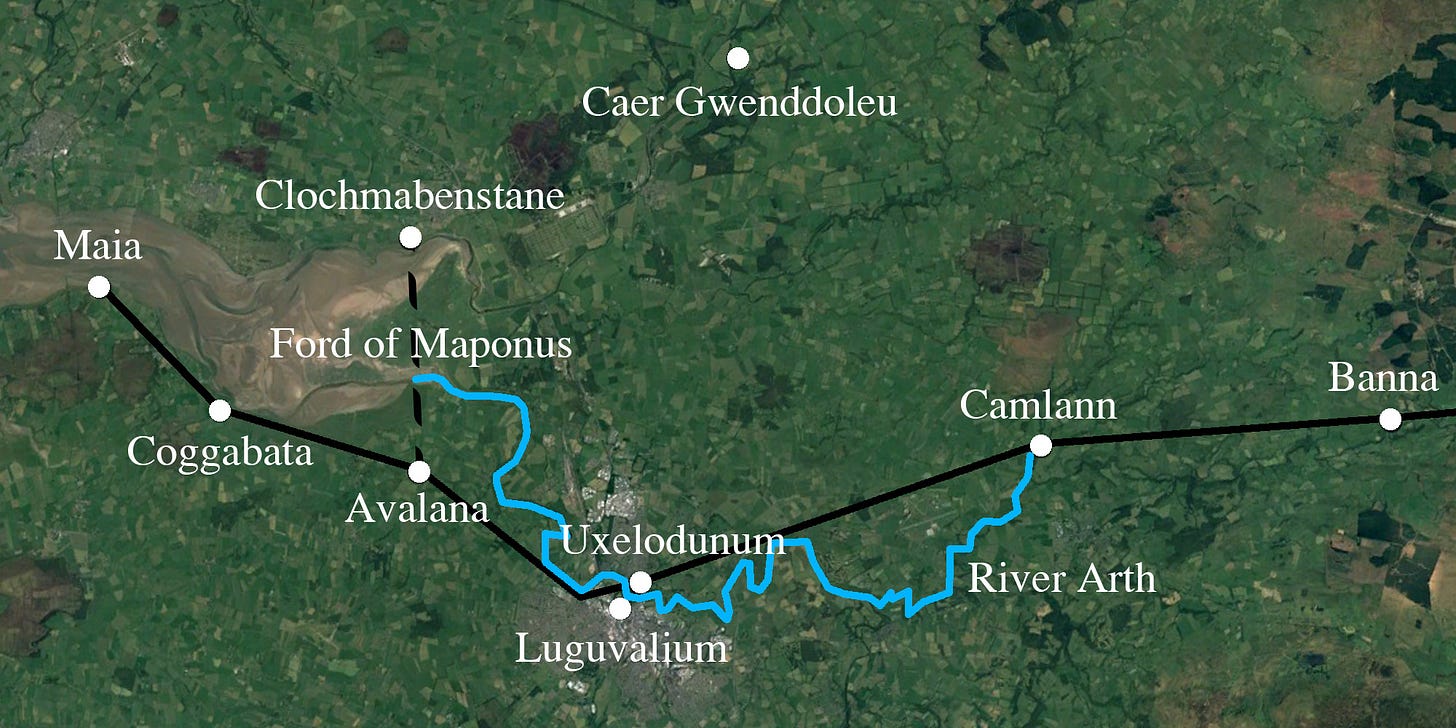

Most scholars agree that the Battle of Camlann was a real event that probably occurred at Camboglanna on Hadrian’s Wall. Arthur died where he first rose to prominence “Around the old renowned boundary” at the hands of a familiar enemy, the Britons of Goddodin and Strathclyde. According to one visceral account of Arthur’s death

“Suddenly a certain youth – handsome in appearance, tall in stature, evoking by the shape of his limbs a strength of immense power... ...hurled the aforementioned missile into the King”

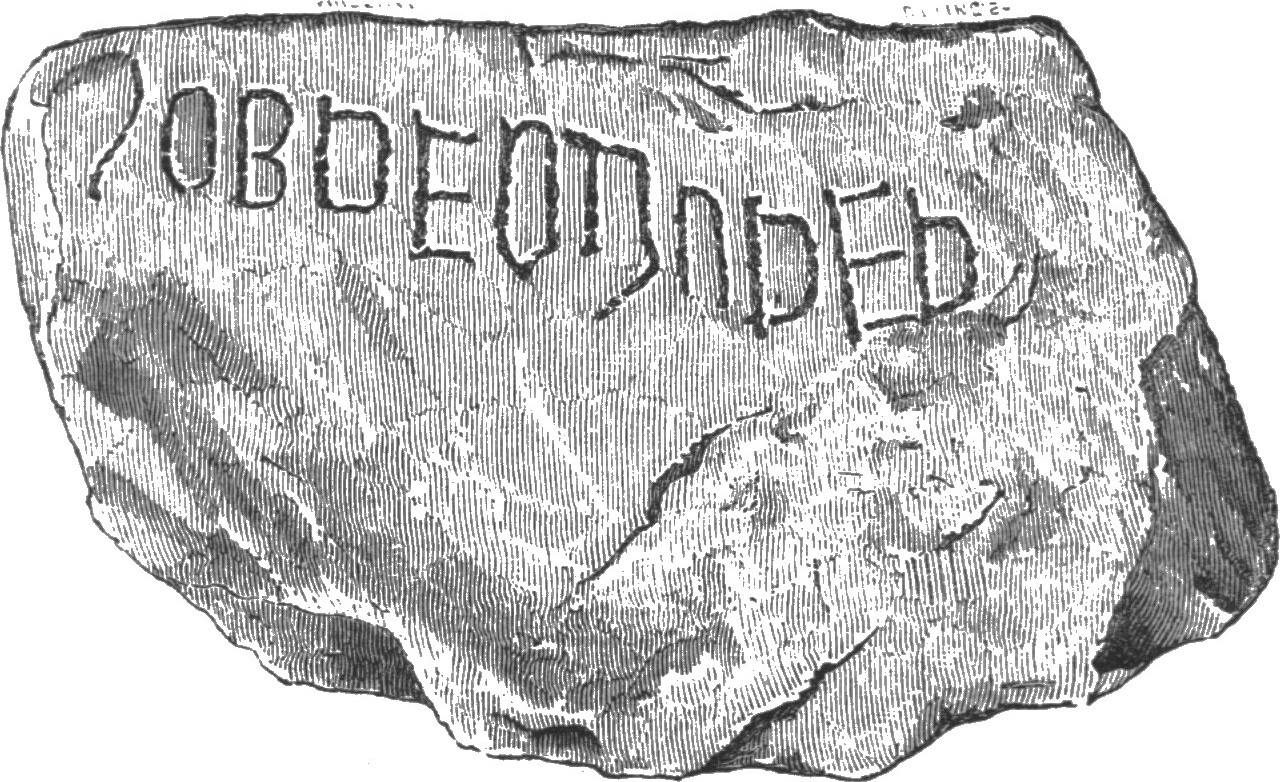

A 6th century inscribed stone has been found at Camboglanna that potentially commemorates the battle. One translation is “SVB DEO AVDEO” meaning “under God I dare”.

Arthur requested to be taken to the “delightful Isle of Avallon” where he died of his wounds. A short distance to the west of Camboglanna is another Hadrian’s Wall fort called “Aballava” which sits in a tidal marsh on the Solway Firth coastline.

In the 7th century Ravenna Cosmograhy “Aballava” is recorded as “Avalana”. This is probably the inspiration for the “Isle of Avalon”.

"But Arthur's grave is nowhere seen, whence antiquity of fables still claims that he will return."

In summary:

This is fascinating! Thank you for putting all this together so cohesively

Will this recurring guest writer also feature in the upcoming book?