Warlords of the Britons: Cassivellaunus

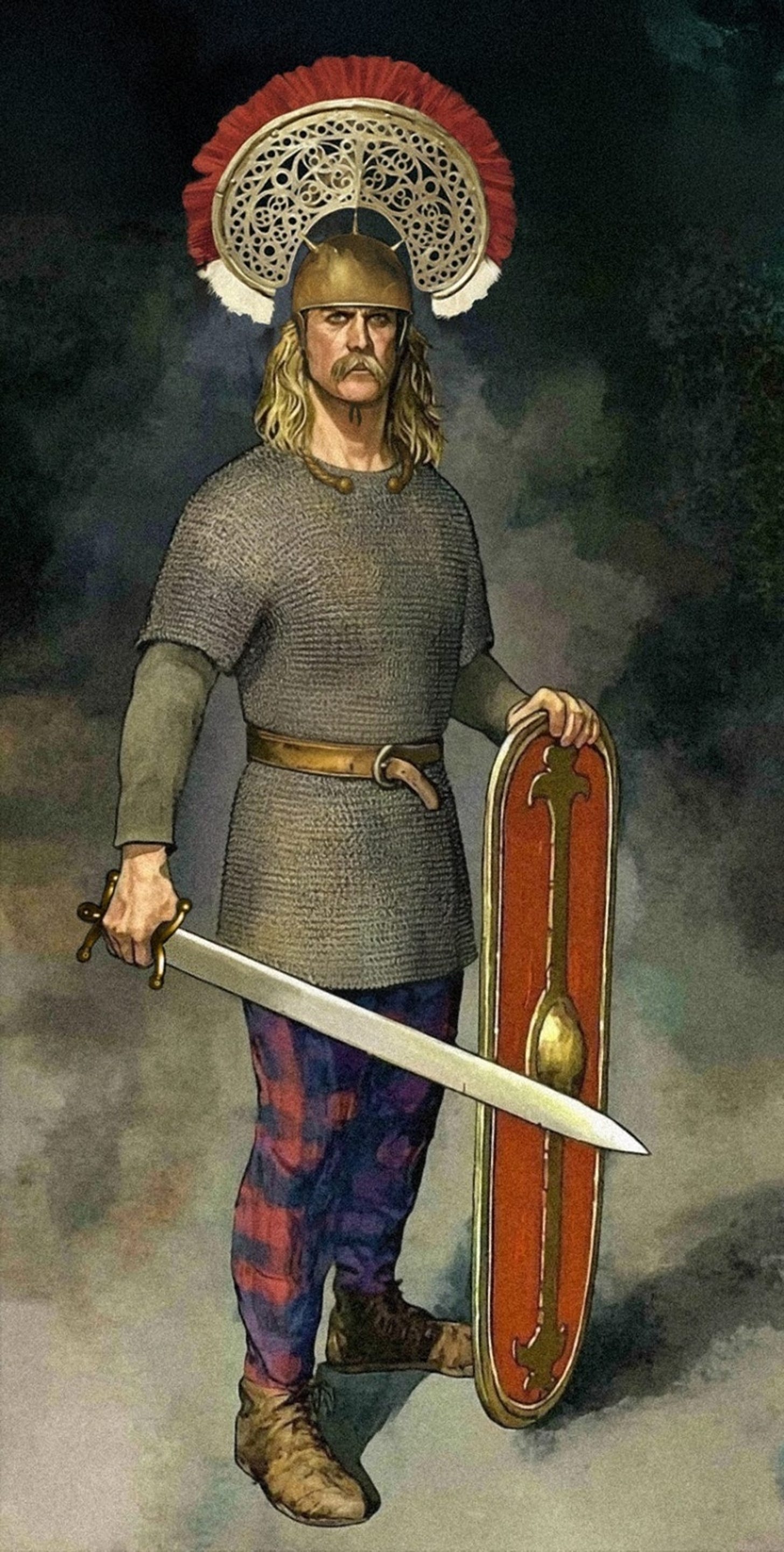

In 54bc Gaius Julius Caesar attempted to invade Britain... again. This time Cassivellaunus was there to oppose him. Caesar began his second invasion with 628 ships, five legions and 2,000 cavalry. He landed unhindered by the Britons this time, and immediately set out to find any military the Britons could muster. The Britons heavily used guerilla attacks, striking with cavalry and fading away. Cassivellaunus meanwhile was raising an Army. A powerful warlord, probably of the Catuvellauni, he had been fighting constantly against his neighbors, most recently defeating the Trinovantes and their king Imanuentius, sending the king’s son Mandubracius into exile.

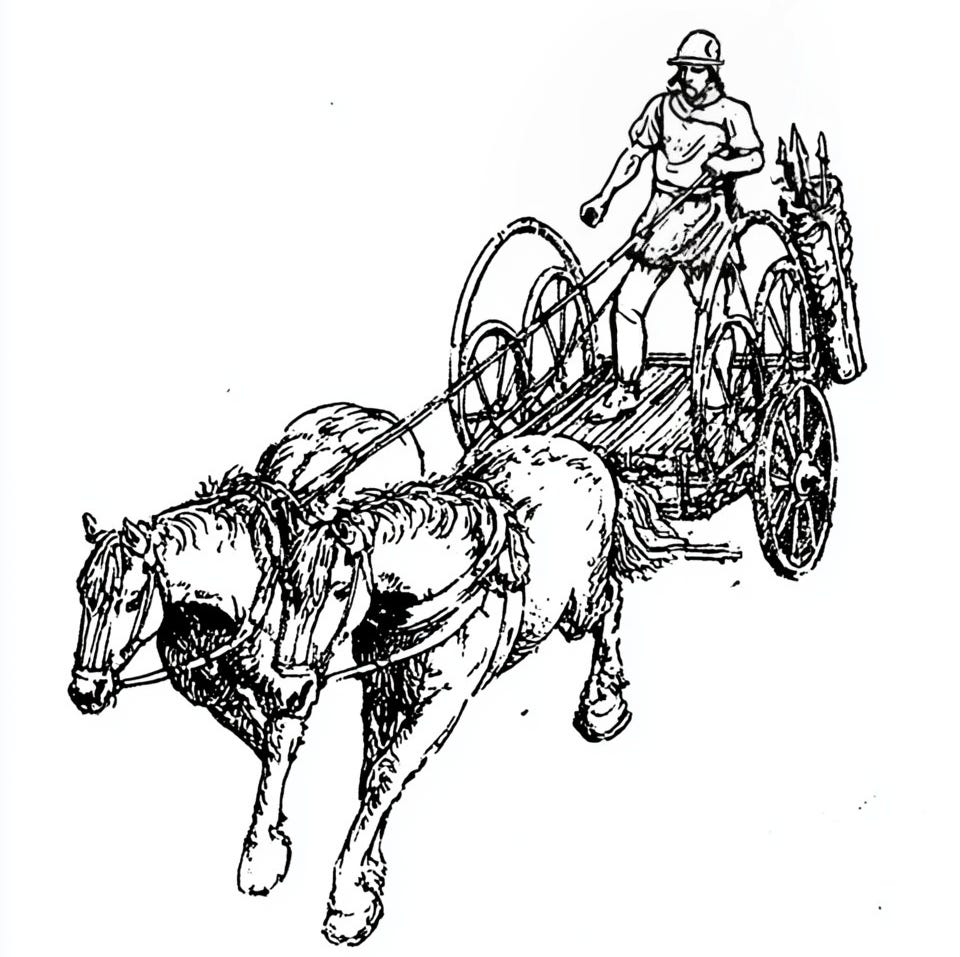

Caesar’s Commentarii (De Bello Gallico V.11–23) gives the only contemporary account of Cassivellaunus. He emphasizes the Britons’ reliance on chariots, noting some “four thousand” of them in Cassivellaunus’ forces. Archaeology, especially the Arras culture chariot burials in Yorkshire, gives independent weight to this description, showing that such warfare was genuinely part of British military practice.

After some failed skirmishes against the Romans, even being routed in one against a foraging party, Cassivellaunus then determined that a direct approach, regardless of the size of his army was futile. He then led an even larger scale guerilla campaign, eventually meeting the Romans while they were crossing the Thames. The Romans managed to make the difficult crossing, beset by Cassivellaunus’ men and stakes place in the river. Cassivellaunus disbands most of his forces after the crossing, and using his cavalry and chariots continues to harry the Romans until Mandubracius and others came forward after surrendering to Caesar, revealing the location to Cassivellaunus’ strongholds. Cassivellaunus initially held out against the siege, even managing to send messengers to four other kings, who then rallied and attacked the Roman camp on the coast, but were ultimately defeated, with the Romans capturing Lugotorix, a Chieftain of the Cantii. Cassivellaunus ultimately surrendered. Mandubracius was then reestablished as king of the Trinovantes, and Cassivellaunus fades away from history, promising to never take up arms again. Neither Cassivellaunus or Mandubracius’ stories end here though, both secured themselves a place in later Brythonic folklore.

Geoffrey of Monmouth remembers Cassivellaunus as Cassibelanus son of Heli (Beli Mawr, possibly inspired by the historical King Cunobelinus) and spins an exaggerated account of both Cassibelanus' life and Caesar's invasions. One can see little snippets of history gleaming through the fiction though, the stakes in the River Thames remembered, and the death of a Tribune. Mandubracius is replaced with Androgeus, a nephew of Geoffrey's Cassibelanus, with the betrayal more personal in his story. All of this was no doubt taken from Caesar's writings, though heavily retold through Geoffrey's lens of narrative, itself tweaked by Welsh Tradition.

While it has been generally held that Caswallawn as Cassivellaunus appears, is a late addition to Welsh Folklore, supposed heavily influenced by Monmouth's work, and certainly some of the Triads that feature Caswallawn do bear the tell-tale mark of Geoffrey’s work, others do not. I think it could be more likely that Geoffrey was instead inspired by this earlier tradition, and in turn influenced it again himself. Combining this early tradition with the writings of Caesar, Geoffrey created his hybrid narrative, neither wholly Caesar, or wholly Welsh.

Part of this earlier tradition is his appearance as an opportunistic usurper to Bran the Blessed. Caswallawn, using a magical cloak that renders him invisible, kills six of Bran’s seven stewards while the King was away in Ireland. Bran’s son Caradog, the seventh steward upon watching the other stewards cut down by a floating sword dies of despair. Caswallawn usurps Bran’s position as King of Prydain. Manawydan, his nephew goes into hiding out of fear of his uncle. Caswallawn fades away shortly after this and isn't mentioned again in the stories remembered by the Mabinogi. It has been suggested that Manawydan is in fact a memory of Mandubracius. There seems to be fragments of a lost tradition of Caesar and Caswallawn fighting over a woman known as Fflur (literally Flower), possibly even a poetic way of referring to the fight for control of Britain, and seems to be quite old and possibly rather free of Caesar's works, as well as Geoffrey’s.

Cassivellaunus through his brief resistance certainly cemented his place in history, and even exists as part of the template that Geoffrey used for his 'Arthur', a warlord resisting invasion, ultimately betrayed by one of his own.

A fascinating summary, thank you. As it happens, I am nearing the completion of a trilogy on Caesar's attempts on Britain, based not only on his Gallic War reports but also on my firm opinion that their purpose was self-aggrandisement in the eyes of the people of Rome and the Senate. Therefore not to be trusted! Would-be dictators still use this approach today...

🌞👍