Think of John Boorman’s ‘Excalibur’ and you’ll have visions of knights in full plate armour on armoured horse, riding down Arthur’s enemies. If Arthur truly did live in the late 5th and early 6th century AD how did this association happen? Are there origins to this trope deeper than Malory? Possibly older than Arthur’s time?

The Obvious

The answer that stares you right in the face is that it comes from Thomas Mallory’s ‘Le Morte d'Arthur’ published in 1470, during the heyday of heavy cavalry wearing plate armour. Readers at the time would have been familiar with the image of a man clad in head to toe steel on a similarly armoured charger. There is a large chance that the Heavy Cavalry trope ends here, and honestly it’s a bit demystifying and stale. While the trope most likely started with the 12th century romances, It was Mallory that perfected and cemented it, but as usual the truth may have some in common with the fiction, if you are willing to dig.

The Horsemen of the North

Within the Brythonic poetic tradition mounted warriors hold a place of honour, and stand head and shoulders above other warriors.

“He was to be admired in the tumult with nine hundred horse.”

-Marwnad Cunedda (The Death-Song of Cunedda)Most pleasing are the wide-coursing rays of dawn,

Most pleasing are the boisterous chieftains of the governor.

Most fine are cavalry soldiers on their sleek military horses,

at the beginning of May at the farmlands of the armies

-Yspeil Taliessin. Kanu Vryen (The Spoils of Taliesin, Poetry for Urien)It has been proposed by scholars such as John Morris, that this tradition of cavalry amongst the sub-roman Brythonic kingdoms was a key factor in staving off the Germanic Invasions of the 5th and 6th centuries. Using the advantage of cavalry’s mobility Arthur (and other Brythonic kings) could have easily maintained border territory, stopping Germanic advances with quick ‘shock and awe’ strikes from cavalry. Striking out from horse-forts along Roman roads, stopping border incursions through strategic dykes and fortifications much like the Romans did in the prior centuries. These later horse-lords could maintain territory effectively, and raid, but would be less effective at taking new territory, ineffective against fortified positions, and in turn reliant upon fortified positions themselves, as surprised cavalry outside of a fort were far more vulnerable than infantry.

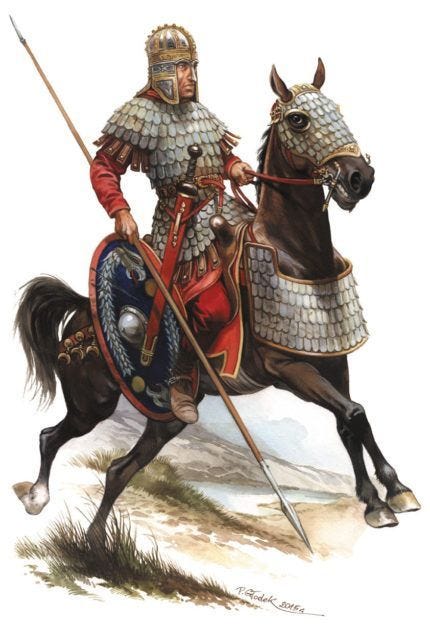

This cavalry would have been far from the Cataphracts of Rome, and further still from the 15th century mounted knight, but still a devastating force on proper ground. Closer to the Roman period some of these especially high-status men may have been armed with scale armour in the vein of the late roman cavalry, and even with armoured horse. Javelins would have been in common use by this cavalry, darting towards infantry loosing their javelins, and turning away from the mass. Repeating this until the enemy was devastated or broken. These warriors would have been the light armoured vehicles of their era, and besides the onslaught of projectiles, and even a determined charge with spear would have been an absolutely devastating possibility with them.

The twelfth battle was on Mount Badon in which there fell in one day 960 men from one charge by Arthur

More common, would have been maille, especially as time passed into the 6th century. These warriors would have looked very similar to the earlier maille-clad lighter Roman cavalry seen in the illustration below. A powerful warlord capable of having a fully kitted and mounted Comitatus would have been able to extend power and impose his will with swiftness and ease.

Men rode to Catraeth with a rallying cry, in

blue-dark armour, their horses fleet, sharp-

pointed spear-shafts raised on high,

blades and mail-coats gleaming.

-Y GododdinEven with relatively unarmoured horses, and a shortsleeved maille shirt, these men would have still been powerful warriors, charging with javelins and spears to great effect.

Mounted Horsemen in the battle’s van

cast spears of holly stained blood

-Y GododdinA Theory With Few Merits

I have voiced my issues with the Sarmatian theory of King Arthur’s origins before, as the theory is heavily skewed and relies on a monstrous amount of “what ifs” that don’t hold water, especially considering the late codification of the Narts Sagas, in concert with the massive pan-european popularity of the later Arthurian stories. It is hard to conclude that the Narts Sagas influenced Arthur, as it seems that it may have easily been the opposite, with the Narts sagas picking up a significant amount of Arthurian material, that or as is always possible, blind coincidence. I generally do not wish to detract from others work, so I don’t spend too much time debunking as I feel it is wasted effort. While Lucius Artorius Castus was likely not Arthur, and very likely had no command over any of the Sarmatian troops in Britain during his time, the Sarmatian cavalry stationed in the north at Ribchester may very well have had an influence on Arthur afterall.

With their Draconarii raised, charging with lance almost head to toe scale and maille armour, armoured horse1, these cavalrymen would have been a terrifying and memorable sight. Between the Sarmatian cavalry and the late-Roman cavalry that were influenced by them and ultimately succeeded them, there was almost certainly a heavy influence on the Brythonic people of the north, cementing the importance of cavalry. The early post-Roman leaders in the north such as Coel Hen, Cunedda, and Ceredig, undoubtedly would have seen the importance of such cavalry and their associated forts in securing their territory. In Marwnad Cunedda (The Death-Song of Cunedda) we get the earlier mentioned line

“He was to be admired in the tumult with nine hundred horse.”

Nine hundred cavalry at this time would have been a formidable force. Coupling this with the potential Roman pedigree of Cunedda, this idea of an enduring northern culture of martial horsemanship doesn’t seem that farfetched. There is evidence of reoccupation of a number of forts on Hadrian’s Wall, as well as many older Hillforts in this time, with many likely hosting these roving cavalry forces. The entire poem of Y Gododdin is written about an ill-fated cavalry force of the Gododdin, a Brythonic northern kingdom (Coincidentally also where Cunedda was said to have come from, or maybe not so coincidentally). Amongst Nennius we might have a little bit more of this cavalry tradition preserved with his entry for Badon which implies a cavalry charge.

“The twelfth battle was on Mount Badon in which there fell in one day 960 men from one charge by Arthur”

This might be our link between the Brythonic poetic tradition, and the Post-Galfridian tradition, giving us a fairly reasonable path from Late-Roman Cavalry to the later knight of the round table. Dark age horsemen, patrolling and raiding, eventually becoming chivalrous Grail-Questing Knights.

While we can’t say for sure that Mallory’s knights in shining armour were drawn from this northern Brythonic cavalry culture, it is an interesting synchronicity that the later fiction is a strange mirror of the truth.

Addonwy, you swore great deeds, as Bradwen did; you burnt, slaughtered, as fierce as Morien; with your clear eye never lost sight of wing or van; your surging furious horsemen gave not an inch to the Saxon.

For more on this, and some implications for Arthuis ap Mar you can check out this twitter thread here

This is not the later stirrup aided couched-lance charge of the knights we are familiar with. This is pre-stirrup, but still likely to have been devastating.

Remember reading or hearing somewhere that Tolkien based Rohan off Mercia. But, I don't remember seeing or hearing anything about a Mercian cavalry or even Anglo-Saxon cavalry. Off the top of your head, was that 'a thing'? Or am I just mis-remembering things?