Guest Feature: @P5ych0p0mp: Arfderydd: A New Perspective.

A New Perspective on the Battle of Arfderydd Based on Place-Name Evidence

Note from Aurochs: Arfderydd represents a very real turning point in the inner-politics of the Brythonic Hen Ogledd. While the cataclysm of the late 530s, Arthwys’ death in 537, and the plague of the 540s were major contributing factors to the decline of the Brythonic kingdoms in the north there were still powerful men gluing it together. First Eliffer Gosgorddfawr, Arthwy’s son, who seems to have ruled competently until his untimely death fighting Ida of Berncia, and then Urien, who stepped forward as the preeminent ruler of his day. p5ych0p0mp gives us an amazing new look at Arfderydd, a battle that lay the pieces in place for the eventually fracturing of the Old North and the downfall of Urien. On to the article!

P5ych0p0mp:

In previous instalments of this series I have considered numerous snippets of place name evidence with varying levels of certainty. Some of these locations originate from folkloric antiquarian projection onto the landscape and others are concrete places that hosted real historical events. This article will add further place names of both kinds filling in some blanks in the map of Rheged. This exercise will in turn perhaps fill in some blanks of real historical events. These are the place names associated with events during the British Heroic Age found within sources such as the works of Taliesin. The following section will briefly summarize some of these previously considered names and some new names. (Disclaimer: my speculations on place names is very amateur-ish).

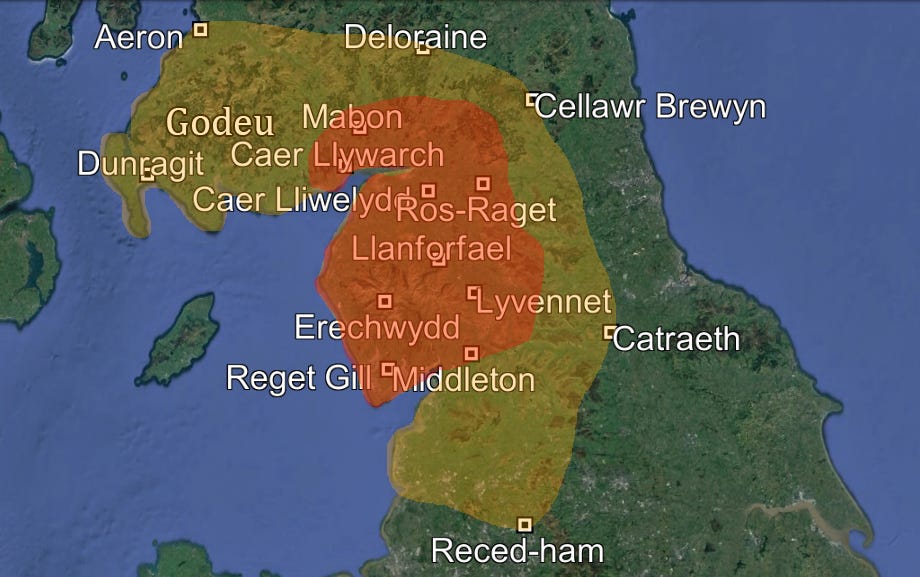

The name most often associated with the territory ruled by Urien is “Rheged”. This name is only attested in Welsh poetry where it is spelled as “Reget” or “Reged”. Of all the territories associated with Urien it is by far the most frequent and prominently used even as an epithet “Urien Rheged”. There is much debate about the exact meaning of “Rheged”, some believe it means something like “Land of Generosity” (Rheg + ed). Others, including myself, do not favour this derivation as most other territorial names found in Taliesin are geographical descriptions such as another of Urien’s titles “Lord of Erechwydd” i.e. “Area of Fresh Water” referring to the Lake District. It is for this reason that I favour the alternative proposed by Alan James which is Rag + ged meaning “Before the Wood” (The Wood in question being the vast Celyddon Forest). This would match another critical place name linked with Rheged found within Taliesin, “Argoed” or Ar + ged meaning “Opposite the Wood” that I will consider later.

The only strong evidence we actually have regarding the exact location of Rheged is a reference in the poetry of Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd who states that “Caer Lliwelydd” modern day Carlisle lies within the territory of Rheged. The phrase “tra merin reget” meaning “beyond the firth of Rheged” occurs in Taliesin which tells us that the territory probably straddled the modern day Solway Firth. “Caer Lliwelydd” is also referenced in Taliesin as a target of Cunedda of Gododdin. This confirms it was probably a populated centre of the Coeling dynasty and in all probability the capital of Rheged.

Rheged is assumed to be the name of Urien’s greater Kingdom because smaller administrative units such as “Argoed”, “Arfynnd”, “Land of Mabon” are implied by Taliesin to be contained within it. For this reason most of the other territories that Urien is stated to rule are also taken as being within the bounds of Rheged. This includes the core territories of “Llwyfenydd” (Lyvennet Valley) and Erechwydd (Area of Fresh Water, Lake District). This largely corresponds to the older Civitas Carvetiorum (roughly modern day Cumbria) stretching down from Hadrian’s Wall to at least the Middleton milestone. It is also implied within Taliesin that Urien ruled Catraeth (Catterick) and Aeron (Ayr) although these do not lie within Rheged itself and probably represent neighbouring territories Urien holds lordship over.

Many seekers have scoured old land surveys searching for further place name evidence for the Kingdom of Rheged. The best match so far is “Reget Gill” in Furness, Cumbria found by Dan Elsworth. This spelling is an exact match of the original “Reget” found throughout Taliesin. This shows that the boundaries of Rheged extended well beyond the Solway region. Another commonly cited place name is “Reced-ham” recorded in the Domesday Book for modern day Rochdale which may indicate the Southern-most extent of Rheged at its peak under Urien, although it does seem anomalously far South. A third often cited place name is “Dunragit” meaning “Fort of Rheged” in Galloway. There is reason to believe Dunragit was an outpost of Rheged within a separate kingdom called Godeu which I will return to later. Others believe that Dunragit actually derives from “Dun Gwaragedd” meaning the “Fort of Women”. Another place name found on the modern North East border of Cumbria is recorded as “Rasw-raget” in 1183. It is commonly thought this contains the same place name element meaning Ros + Gwaragedd or “High ground of women”. However I think that Ros + Raget meaning “High ground of Rheged” is more likely with the erroneous “w” a simple scribal error.

Some other less secure and highly speculative place names may contain references to Rheged. In 1592 a “Riggat Grange” is recorded in Borrowdale, Cumbria possibly meaning “Rheged Villa”. This is a valley already confirmed as a high status 6th century hunting estate by the poem “Pais Dinogat”. There is also a “Regen-dale” recorded in 1522 near Shap, Cumbria.

One of the most common toponyms found in Cumbria is “Rigg”. It is an Old English element meaning “Ridge”. Somewhat curiously a simple search of places starting with “Rigg” on the Survey of English Place-Names (https://epns.nottingham.ac.uk/) shows clearly that Cumbria has by far the greatest density anywhere in England. This is highly counter-intuitive as you would expect the historically “least English” North West to have the lowest density. One explanation could be the heavy Norse influence in Cumbria. The Norse and Old English naming convention would be to place the “-rigg” element at the end of the placename like "Haverigg” meaning"the hill where oats are grown" whereas the Brittonic naming convention would be to place the “Rag-” element at the start of the place name such as “Rag-ged” (Rheged). The earliest form of Old English “Rigg” is “Ryg” and according to Alan James “Rag-” should have evolved into “Rhyg-”. It is easy to see how the Brittonic “Rhyg” could be mistaken and adopted as “Ryg” by Anglian and Norse settlers. One example of this could be the placename “Drumlanryg” recorded in 1384. The first two elements are Brittonic: Drum (Ridge) + lanerc (Clearing). The third element “ryg” could be the Germanic “ridge” (ryg) or the Brittonic “before” (rhyg). The full Brittonic “Ridge before the clearing” would seem more coherent to me. Although if we conservatively assume all place names ending in “rigg” are Germanic this still leaves the unorthodox place names that start with “Rigg-” in line with the Brittonic naming convention. If we search for such place names starting with “Rigg” we find that almost exclusively in Britain they are found in the region that was formerly Rheged. They are most heavily clustered around the Solway Firth and the so called “Brampton Enclave” (An area known for its density of Brittonic place names). This may be a case of confirmation bias but it is certainly curious and perhaps warrants investigation by a more knowledgeable linguist. The following are just some examples found: Rigg (at Gretna), Rigg (at Gilsland), Rigg (at Hesketnewmarket), Rigg (at Knott), Rigghead (at Rigg, Gretna), Rigghead (at Kirklinton), Righead (at Bewcastle), Rigghead (at Hethersgill), Rigghead (at Coniston), Rigghead (at Borrowdale), Rigghead (at Threlkeld), Rigghead (at Dumfries), Rygehead (at Shap) and Rigghead (at Settle). Again it is easy to see how Norse settlers could reinterpret “Rhyg-ed” (Rheged) as “Ryg-head”. The phrase “Ryg-(h)ead” spoken with a certain accent (omitting the “h”) sounds almost indistinguishable from Rhyg-ed. It should be noted that it is far more likely that all the “Rigg” place names derive purely from original Norse but it is also certainly curious that the common Cumbrian “Rigghead” doesn’t seem to occur anywhere else in Britain (except South West Scotland) thus I thought it worth mentioning.

In previous articles I mentioned other place names within the borders of Rheged with relevance to the British Heroic Age. Briefly summarised: Avalan or Aballava (Avalon), Camboglanna (Camlann), River Arth (Connecting Avalan and Camlann), Land of Mabon (Lochmaben or Maben on Old Maps & Clochmabenstane), Ford of Maponus (The Sul Wath Ford), Pow Donnet (Stream of Dunod), Cardunneth (Caer Dunod, Fort of Dunod), Castel Owain (Site of Arthurian romances and Urien’s son), Llanforfael (Dacre burial site of Owain), Aber Lleu (Ross Low site of Urien’s death), Celyddon (Caledonian Forest – the vast swathe of forest beyond Hadrian’s Wall that exists to this day), Arfderydd (Arthuret), Carwhinley (Caer Gwenddoleu site of Myrddin’s descent into madness).

I will briefly outline some more locations to this Arthurian Atlas before we proceed to the main thesis of this article. Antiquarian projection explains the origins of such place names as Pow Dunod and Caer Dunod. Dunod the Stout did not rule these areas that comprised the core territory of Rheged, he ruled a territory called “Regio Dunatinga” centred on modern Dentdale probably as another client King under Urien. Although it is possible he briefly held these core areas in the chaos following Urien’s assassination before being driven out by Owain and Pasgen. This means the place names commemorating Dunod are probably a result of later British populations romanticising monuments in the landscape with a prominent name from their folklore. Dunod was the son of Pabo the Pillar of Britain. Pabo was another prominent figure in the British Heroic Age and is commonly thought to be the son of King Arthwys. This is unlikely however as he is probably actually son of Ceneu ap Coel making him an uncle to Arthwys. Pabo also ruled Regio Dunatinga which makes the following place name in the heart of Rheged equally curious to that of his son. The earliest form of Papcastle near Cockermouth is recorded as Pabecastr in 1260. This is thought to mean the “Castrum of Pabo”. Much like his son this is also likely to be a case of later antiquarian projection.

As covered in previous articles Dunod ap Pabo was an enemy of Urien and his sons. The place names Cardunneth (Caer-Dunod) and Pow Donnet (Pow Dunod) likely commemorate him and his conflict with Rheged. It is curious that in traditional Cumbrian dialect, even still in use today, is the term “Donnet” which is used to describe a person who is worthless or evil. This may be further evidence of a folk memory of Dunod. Roughly a mile South of Caer-Dunod at a place called “DunWalloght Castle” is another possible case of antiquarian projection. I believe this could be another romantic memory of a prominent figure from the British Heroic Age namely Gwallog ap Lleenog. “Dun-Walloght” could translate as “Fort of Gwallog”. The close proximity of the “Fort of Gwallog” to the “Fort of Dunod” could further strengthen the theory that a population of Britons in this locality named monuments in memory of folkloric figures of the British Heroic Age.

Returning to the ruling dynasty of Rheged itself we can identify a string of place names potentially commemorating four generations. Previously mentioned in another article we have Castell Owain in the heart of Rheged which was used as the setting for multiple late Arthurian romances. About one mile North of Castell Owain is the source of a stream called “Pow Maughan”. According to Alan James “Maughan” is an alternate spelling of the Brittonic “Meirchion”. Owain’s Great-Grandfather was Meirchion Gul or Meirchion the Lean. The name “Meirchion” was adopted as a Brittonic name after the rule of Emperor Marcianus in 457. Meirchion the Lean was probably born around 460 which shows that even in the late 5th century the Britons of Rheged were highly Romanized. I would assert that “Pow Maughan” commemorates Meirchion the Lean and should be translated as “Stream of Meirchion the Lean” for the purposes of our romantic atlas.

Moving further north into the murky Forest of Celyddon we find a cluster of hill forts and settlements the largest of which is Castel Oer. I have been unable to source any scholarly etymology for “Oer” so in the absence of expertise I will insert my own speculation that this hill fort is named after the son of Meirchion Gul namely Cynfarch Oer. The cognomen “Oer” is normally translated as meaning cold or dismal. This place name identification shouldn’t be taken as authoritative in any way as it is based purely on my amateur speculation.

This leaves us with a gaping absence of any place names for the famous son of Cynfarch the Dismal. As the most praised hero in poetry Urien should have the most place names much like Arthur. In my investigations I have only been able to dig up a single example. Further north and even deeper into the Forest of Celyddon next to the Ettrick Water Alan James has linked the cluster of “Deloraine” place names such as Deloraine Burn, Wester Deloraine and Easter Deloraine to Urien. He identifies “Deloraine” as meaning Del + Urien of “Valley of Urien”. This “Valley of Urien” is at roughly the same latitude as Aeron (Ayr), which may indicate this was the North Eastern boundary of Urien’s territory before the Siege of Lindesfarne and his assassination. There is another “Deloraine” found in Cliburn, Cumbria however this is the name of a private dwelling and could be a modern invention after a literary character. I have been unable to access the old enclosure map of the area to confirm if an older field name exists. There is also the similar “Dollerline” applied to an early medieval settlement at Bewcastle (Next to one of the previously mentioned “Rigghead” toponyms). “Dollerline” probably means “Valley of Lyne River” but it could also be a late corruption of Dol + Erien or “Valley of Urien” although this is less likely. “Castel of Owain”, “Valley of Urien”, “Castel of Cyfarch Oer” and “Stream of Meirchion Gul” potentially gives us place names for four generations of the same dynasty.

In my previous articles I analysed the Battle of Argoed Llyfain in which Urien and Owain defended their land from a raid. I now believe this previous analysis to be incorrect. The opening lines of the poem by Taliesin include:

“Flamdwyn hastened in four hosts:

Godeu and Rheged were mustering

to Dyfwy, from Argoed to Arfynyd."

And at the end of the poem it includes the lines:

"And in front of Argoed Llyfain

There were many corpses.

The ravens were crimson because of the warfare of men”

Before we re-analyse the events of the poem first we will attempt to accurately identify all the place names included within the narrative in order to get an accurate idea of the geography. Firstly the mention of “Godeu and Rheged” as areas under the protection of Urien and Owain. We have already considered the extent of Rheged as the name of Urien’s greater core Kingdom. The implication of the phrasing “Godeu and Rheged were mustering” is that they are neighbouring areas both ruled by Urien. This immediately narrows down our search for “Godeu”. Another mystical poem by Taliesin called “Cad Godeu” is usually translated as “Battle of the Trees”. If Rheged does mean “Before the Woods” as previously deduced then a neighbouring region called something like “The Woods” (Godeu) would be a nice fit. This would make Godeu roughly synonymous with the Forest of Celyddon. Many scholars identify “Cad Godeu” with one of Arthurs battles namely “Cad Coed Celyddon” or the “Battle of Celyddon Forest”. The poem Cad Godeu mentions a “Caer Nefenhyr” as a location within the region. Marged Haycock has demonstrated that this name derives from “Novantorix” or “the king of the Novantae tribe”. The Novantae were recorded by Ptolemy as residing in South West Scotland corresponding roughly to modern day Galloway. It is a heavily forested region within the broader Forest of Celyddon and is next to the territory of Rheged and so this seems like a solid identification.

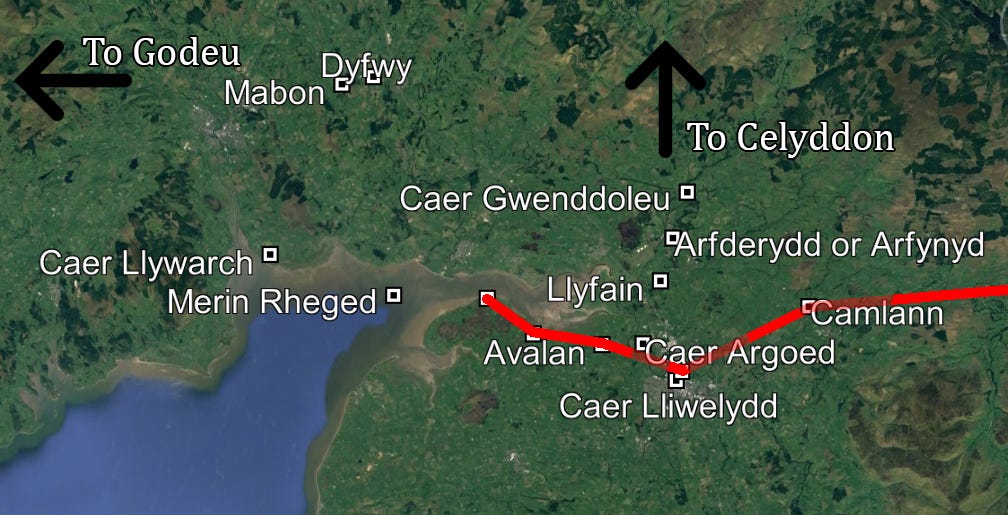

The next location to identify is “Dyfwy” where the forces of Rheged and Godeu mustered. The logical implication here is that “Dyfwy” is somewhere between the two Kingdoms of Urien. Alan James says this is probably the name of a river meaning something like “brightly shining one” but he does not speculate which river this could be. A simple search of river names in south west Scotland returns two potential options. The River Dee in Galloway which is probably too far west to be a midway mustering point between Rheged and Godeu. The second option is much more promising called the Dryfe Water. The Dryfe Water flows into the River Annan at Lochmaben. This area is known as the “Land of Mabon” in the poetry of Taliesin which is significant for reasons we will return to later. The etymology of “Dryfe” is unknown, even the language, therefore I would propose it could derive from “Dyfwy”.

The next location is “Argoed” and “Argoed Llyfain”. Previously I have identified “Argoed Llyfain” with “Llwyfenydd” or the Lyvennet Valley due to the shared “Llyfain” element meaning Elm trees. After further research I now believe this is incorrect and “Argoed Llyfain” is an entirely separate location. As the location of the battle itself it should be somewhere relatively near Godeu and the mustering point of the Dryfe Water thus ruling out the Lyvennet Valley. “Argoed Llyfain” or Ar + ged + Llyfain means “Opposite the Elm Wood”. Another clue comes to us in the poetry of Llywarch Hen who was a cousin of Urien and ruled as a client King within Rheged. Llywarch ruled from Caerlaverock on the Northern shore of the Solway Firth just south of the “Land of Mabon” and “Dyfwy”. Caerlaverock was originally “Caer Llywarch” but was confused in later centuries into “Caer Laverock” meaning “Fort of Larks”. In some of his poetry Llywarch says “the men of Argoed have ever supported me”. This tells us that we are searching somewhere in the vicinity of Caerlaverock for “Argoed”. Scholars including Alan James identify the etymology of the River Lyne which flows into the Solway Firth as deriving from “Llyfain”, some go further and explicitly identify the River Lyne with “Argoed Llyfain”. This seems like a strong identification, the River Lyne flows out of the Forest of Celyddon into to Solway basin. The names Rheged (Before the Wood), Godeu (The Wood), Argoed (Opposite the Wood) all seem to be measured relative to the imposing massif of the heavily forested Southern Uplands of Celyddon beyond Hadrian’s Wall. This tells us something about the effect on the psyche this looming presence had on those residing in Rheged.

The names “Argoed” and “Argoed Llyfain” are actually separated within the works of Taliesin and Llywarch. This would lead me to believe that “Llyfain” was a river running through the larger region of “Argoed”. The Taliesin poem says warriors were mustering “from Argoed to Arfynyd”. Another place name just three miles south of where the River Llyfain flows into the Solway Firth is Cargo just outside Carlisle. I believe that Cargo could be originally derived from “Caer Argoed” eventually contracting to its modern form Cargo. Cargo is positioned just in front of Hadrian’s Wall. This leaves the last remaining location of “Arfynyd” yet to identify. The only known place name in the area that is remotely similar to “Arfynyd” is “Arfderydd”. The famous location of “Arfderydd” is recorded in relatively late sources, it could be that “Arfynyd” is an older and more accurate iteration of the name. It means something like “Before the Mountains” which would be an accurate description of modern day Arthuret which sits just before the hills of the Southern Uplands of Celyddon into which Myrddin fled after the Battle of Arfderydd. Arfderydd is just north of the River Llyfain which would fit the context of the poem. It could be that the area South of the River Llyfain to Hadrian’s Wall was the area known as “Argoed” and the area North of the River Llyfain to Carwhinley or Caer Gwenddoleu at the River Liddel was known as “Arfynyd”. Urien and Owain could easily dispatch cavalry from their seat at Caer Liwelydd and Uxelodunum Northwards mustering warriors in the buffer zones of Argoed and Arfynyd and joining the warriors of Godeu at Dyfwy.

Both myself and Aurochs have previously written about the details of the Battle of Arfderydd but the brief synopsis is Peredur and Gwrgi of Ebrauc and Rhydderch Hael of Strathclyde attacked the stronghold of Gwenddoleu ap Ceidio at Caer Gwenddoleu in Arfderydd. Gwenddoleu was killed along with the bulk of his forces. His bard Myrddin went mad and fled into the Forest of Celyddon becoming the legendary prophet. Myrddin recounts his tale to a sympathetic ear found in fellow Bard of Rheged Taliesin in “The Dialogue of Myrddin and Taliesin”. This battle occurred in 573 which is during the floruit of Urien and his son Owain. Arfderydd was a territory within the boundaries of Rheged and as such Gwenddoleu was a client King under Urien much like neighbouring Llywarch Hen. As Aurochs has previously written about extensively Arfderydd was set up by Arthwys as a buffer zone to protect the heart of Rheged and Coeling territory from the Northern threat posed by Gododdin, Strathclyde, Pictland and others. This is also where Arthwys was killed in the Battle of Camlann in 537 repelling this very northern threat.

Utilising the Roman infrastructure of Hadrian’s Wall Arfderydd was a very well defended zone rich with assets and as such it was an alluring target. This is why there was such a high density of raids and battles in the area from Cunedda targeting Caer Liwelydd, Camlann, Arfderydd and as we have identified Argoed Llyfain. It has long been puzzling to many investigators that there is no mention of the High King Urien or his son Owain playing any part in the Battle of Arfderydd in the heart of their Kingdom. As previously outlined by myself, Aurochs and of course John Koch the Battle of Catraeth in 580 was a hugely significant conflict, read Aurochs excellent recent summary here1. The basic synopsis of the battle is a coalition of forces from Gododdin, Strathclyde (Rhydderch Hael), Ebrauc (Peredur and Gwrgi), Bernicia and others marched on the stronghold of Catterick. They were met and comprehensively beaten by Urien with a coalition of forces from Rheged, Elmet and Deira.

It is inconceivable to me that the same coalition of Peredur, Gwrgi and Rhydderch Hael could march on the heart of Rheged and kill Gwenddoleu without Urien coming to his aid. These invaders were clearly bitter enemies of Rheged. I believe the reason that there is no mention of Urien or Owain at the Battle of Arfderydd is because they were pre-occupied repelling the simultaneous raid of Flamdwyn at the Battle of Argoed Llyfain. The opening lines of the Taliesin poem recounting the Battle of Argoed Llyfain says:

“Flamdwyn hastened in four hosts:

Godeu and Rheged were mustering

to Dyfwy, from Argoed to Arfynyd."

If my assertion is correct that “Arfynyd” is in fact “Arfderydd” this directly indicates simultaneous conflict in both Arfderydd and Argoed Llyfain. As we know Urien and Owain were engaged at Argoed Llyfain this would neatly explain their absence from Arfderydd. “Flamdwyn hastened in four hosts” tells us there were four armies attacking different areas of Rheged. In the Taliesin poem “Death-Song of Owain” “Flamdwyn” meaning Flame-bearer is identified as an Angle (“Lloegyr”) who was subsequently killed by Owain:

“When Owain slew Flamdwyn”

“A wide number of Lloegyr went to sleep”

It is evidenced in the Historia Brittonum that “Flamdwyn” was probably Theodric of Bernicia. We already know from the Battle of Catraeth that Bernicia were allied with Peredur, Gwrgi and Rhydderch Hael against Rheged. This means that an Angle host repelled at Argoed Llyfain joining the further two hosts of Peredur (& Gwrgi) and Rhydderch Hael ravaging Arfderydd shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. As it is stated there were four hosts in the attacking force this leaves one remaining to be identified. There are a number of other smaller participants stated to be present at Arfderydd such as Dunod the Stout but I think the fourth host could be another.

In the triads listed under the “Three Futile Battles” it is stated the cause of the Battle of Arfderydd was because of a “Lark’s Nest”. Many scholars take this as a reference to the previously mentioned “Fort of Larks” or Caerlaverock which was the Caer of Llywarch Hen. As Llywarch states in his poetry “the men of Argoed have ever supported me”, this indicates he was perhaps another target during this large scale raid. In the Death Song of Urien by Llywarch Hen he says:

“Morcant and his men planned

to exile me and burn my lands.

A mouse, scratching at a cliff!”

It is for this reason that I believe the fourth host was lead by Morcant Bulc repelled by Llywarch at Caerlaverock. It is unknown where Morcant’s Kingdom was, some have speculated Bryneich, Strathclyde, Dumfriesshire and others Gododdin. The idea that Morcant was a King of Gododdin is very interesting but beyond the scope of this article. It would certainly not be like Gododdin to miss an opportunity to raid Rheged. It could further explain why Morcant was motivated to have Urien assassinated during his siege of the Bernicians on Lindesfarne. Previously I had assumed that Urien, Morcant, Rhydderch Hael and Gwallawc were initially allies due to my interpretation of the Historia Brittonum but it is increasingly looking like only Gwallawc was actually his ally.

Another poem by Taliesin called “Tidings Have Come to Me from Calchvynyd” contains what could be references to the same events in Argoed Llyfain. The bulk of the poem describes Owain defending Cattle from raiders in the “Land of Mabon”:

“Whoever saw Mabon on his white-flanked steed,

as men mingled, contending for Rheged' s cattle,

unless it were by means of wings that they flew,

only as corpses, would they go from Mabon.

Of encounter, descent, and onset of battle

in the realm of Mabon, the inexorable chopper;

when Owain fought to defend his father's cattle”

As we previously mentioned the mustering point of Owain and his troops from Rheged and Godeu was “Dyfwy” which is right in the centre of the “realm of Mabon” where the Dryfe Water flows into the Annan at Lochmaben. It is very likely therefore that the events of this poem depict a continuation of the same series of skirmishes that include also the Battle of Arfderydd and the Battle of Argoed Llyfain. The poem also tells us a sequence of chronological events that happened next:

“The manifestation of Mabon from the other-realm,

in the battle where Owain fought for the cattle of his country.

A battle in the ford of Alclud, a battle in the Gwen”

This indicates that the forces of Rheged conducted their own retaliatory raid against the stronghold of the Kingdom of Strathclyde at the ford near Alt Clut near Dumbarton Rock. We learn in other poetry of Taliesin that Urien was accompanied by his close ally Gwallawc of Elmet in his campaign in Aeron. In further poetry we learn that Urien fought an Anglian opponent called “Ulph” at the Battle of Alclud Ford. This could indicate that Strathclyde were employing Angle warriors from their Bernician allies as mercenaries to protect them.

The “Battle in the Gwen” seems like a reference to the Battle of Gwen Ystrad or Gwensteri which is the name used by Taliesin for the Battle of Catraeth as demonstrated by John Koch. If my analysis is correct it seems that the Battle of Arfderydd and Battle of Argoed Llyfain are direct precursors to the Battle of Catraeth just seven years later featuring many of the same protagonists. These three battles are all defensive in nature but it should be noted that Urien regularly launched his own raids expanding his territory into that of his enemies. The Battle of Alclud Ford, the cattle raid on Manaw Gododdin, the Battle of Cellawr Brewyn (High Rochester) and his Siege of Lindesfarne can all be seen as examples of Urien’s offensive capabilities. This internecine conflict ultimately proved destructive for all parties involved except the Angles who seem to largely watch from the sidelines as the Britons destroy themselves. If Morcant was a King of Gododdin his assassination of Urien at Lindesfarne could be seen as a direct response to the crushing defeat of Catraeth.

Seemingly only one thing is certain in the saga of the Hen Ogledd as summarized by the accidentally humorous Taliesin:

“May the happy country of Urien be filled with blood.”