Special Guest Feature @p5ych0p0mp: Part 3: Some Lesser Known Monuments to Arthur and Owain

Part 3: Some Lesser Known Monuments to Arthur and Owain

The setting of many medieval Arthurian romances was inspired by the real locations of events in the British Heroic Age. These historical events were often projected onto the place names of the landscape of the Hen Ogledd (Old North). In this article I will attempt to decipher a few of these lesser known real world monuments and locations which will in turn shed further light on the historical events themselves. The main focus of this article centres predominantly on locations relating to the deaths of firstly Owain mab Urien and then Arthwys mab Mar.

As outlined in the first part of this series, during the siege of Lindesfarne a conspiracy was unleashed against the Kingdom of Rheged whereupon Urien was assassinated by his former allies. Uriens cousin Llywarch Hen cut off his head to preserve and protect it carrying it back to the “land of Mabon” in Rheged.

A head I bear by my side,

The head of Urien, the mild leader of his army

And on his white bosom the sable raven is perched.

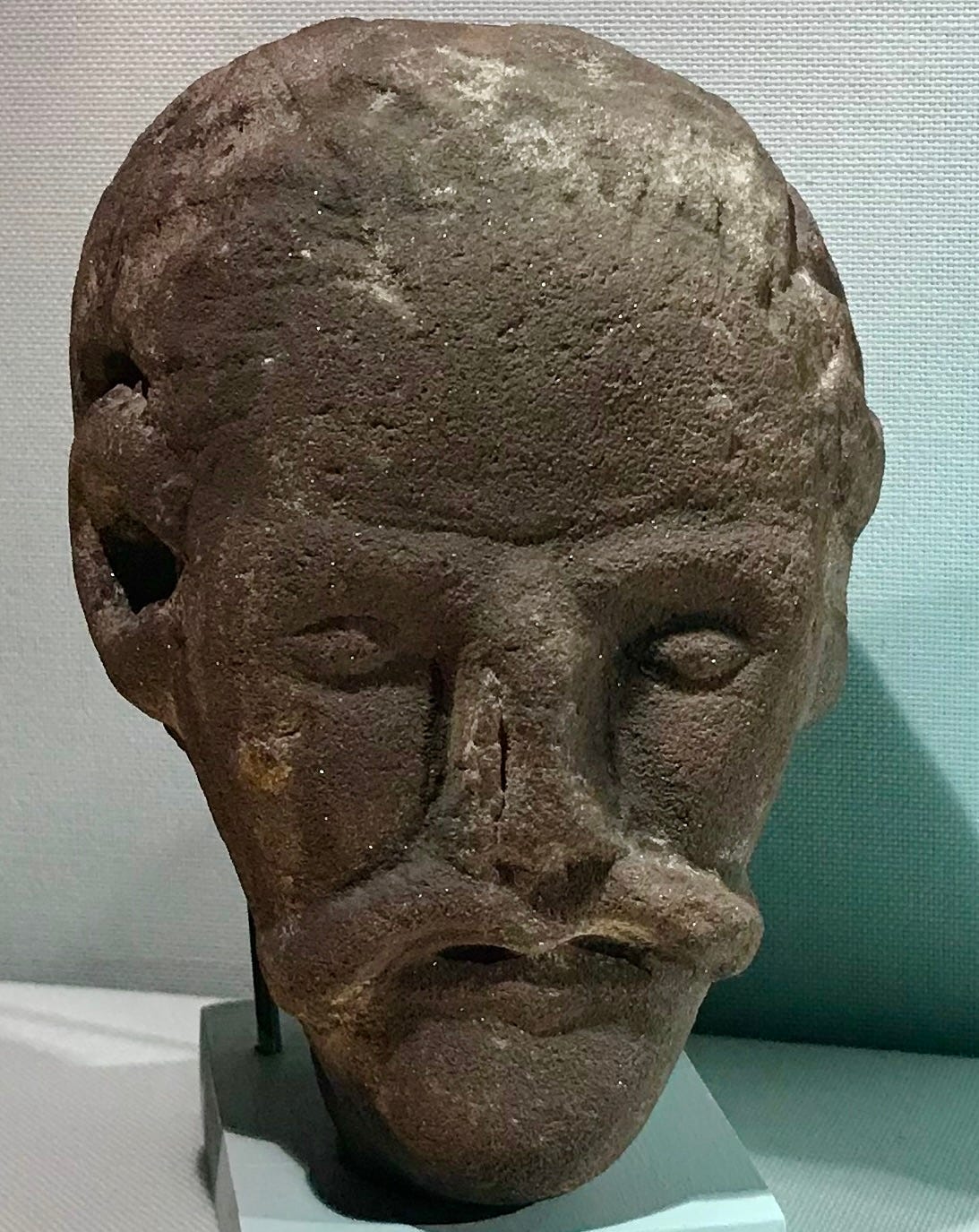

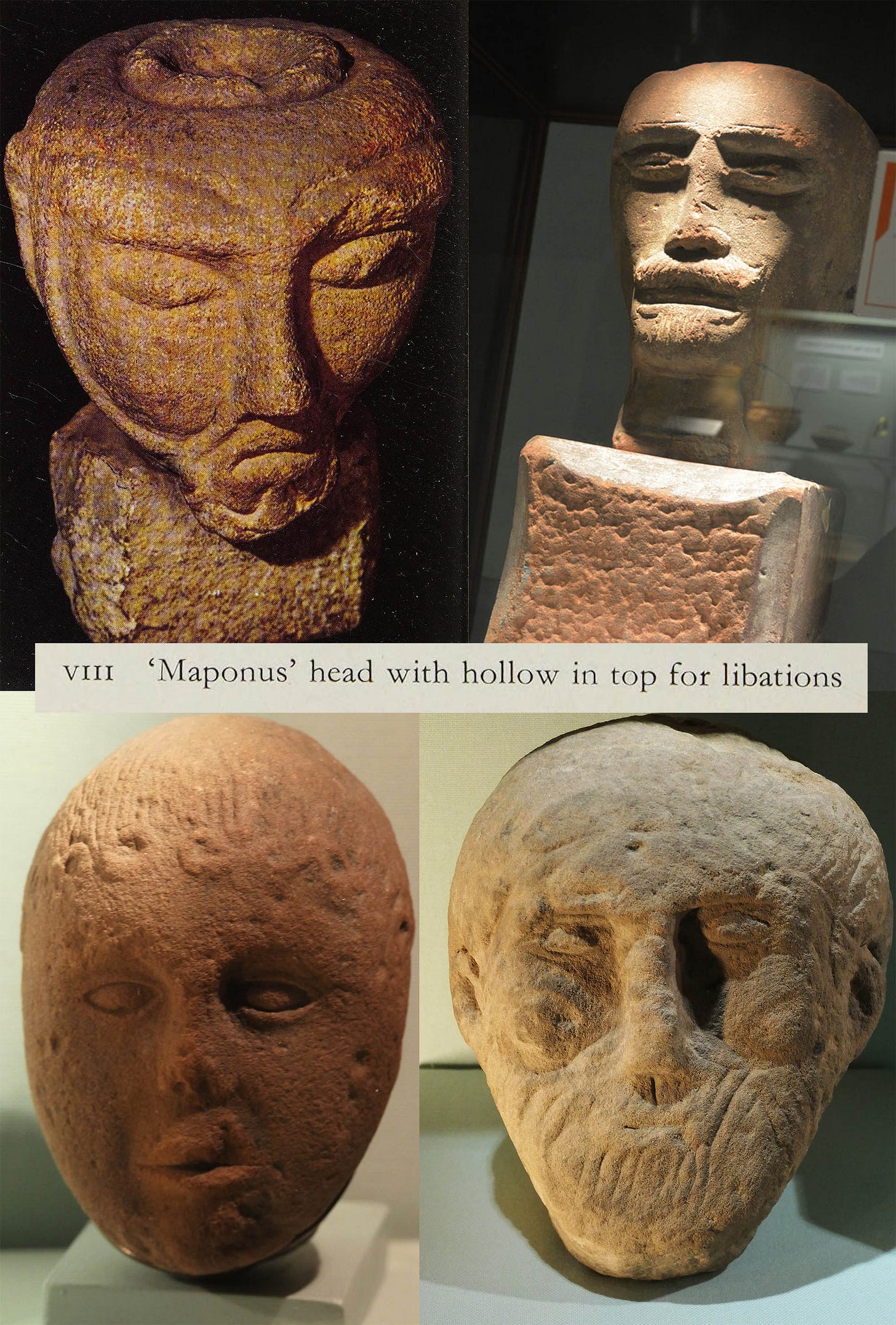

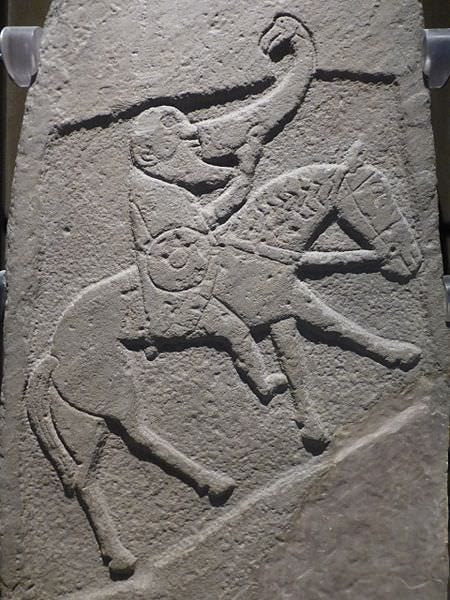

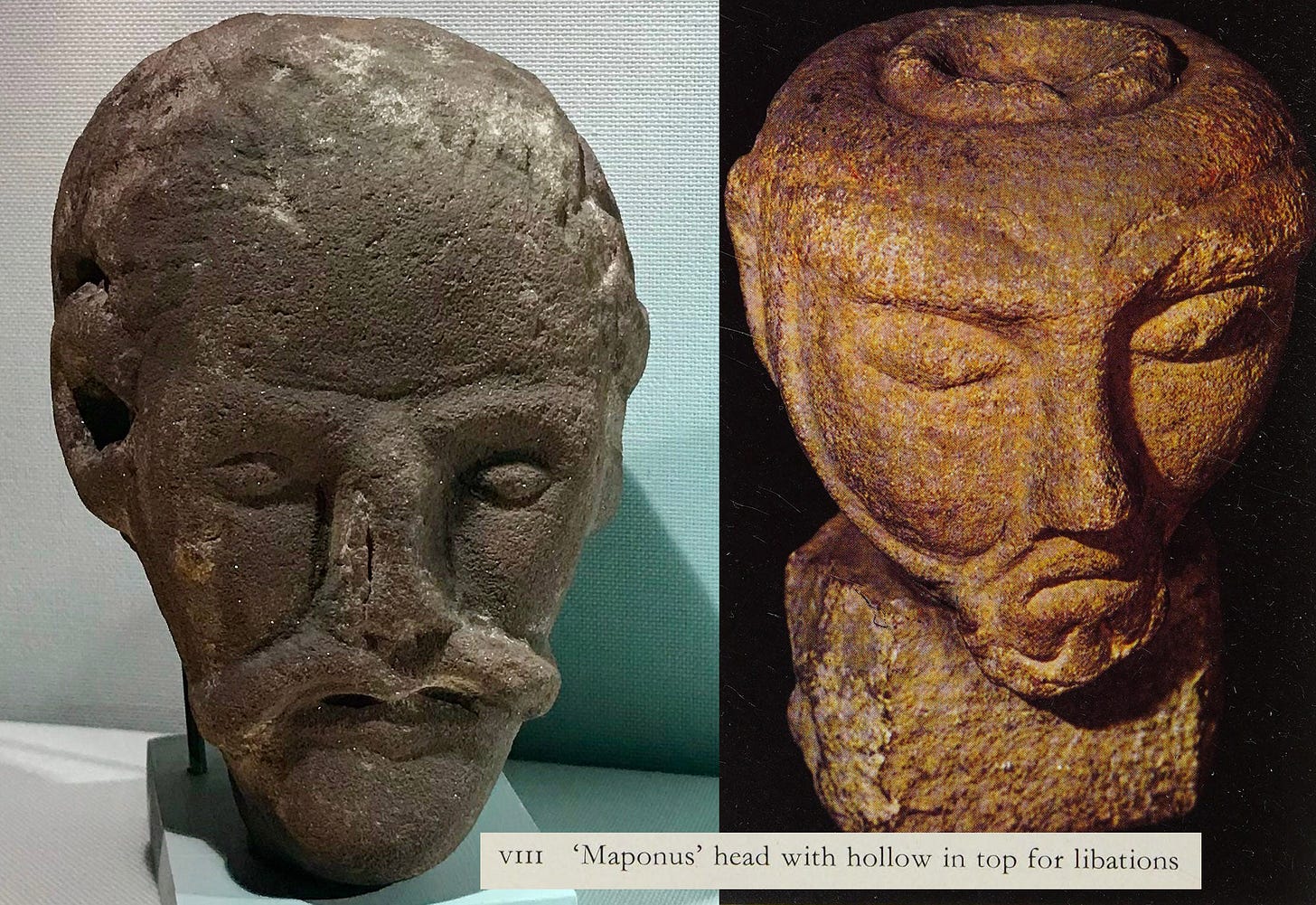

The severed head motif is commonly associated with the Romano-British God Maponus or Mabon and many Celtic votive stone head artefacts in the area are thought to depict Maponus. These eerie depictions of the British Gods give us a glimpse into the image of the decapitated Urien himself.

Following Uriens death, his purportedly divinely conceived son Owain, himself an incarnation of Mabon, became ruler of Rheged. We shall be returning to the significance of this relationship to Mabon ap Modron later in this article. In the ensuing chaos after his fathers assassination Owain and his brothers were set upon by Morcant, Bran, Gwallawc and Dunod who each opportunistically raided Rheged. This conflict killed most of the participants and hugely weakened each Kingdom which ultimately lead to the Angles conquering the Old North. It is unclear precisely which of these enemy kings killed Owain but it is most commonly thought to be Morcant. As theorised in the first part of this series, Gwallawc was eventually killed by Owain's brother Rhun and Morcant was probably killed by Rhydderch Hael.

The only evidence we have for which king actually directly attacked Owain in this period comes from the “Death Song of Urien” by Llywarch Hen:

Dunod, horseman of the chariot, planned

to make a corpse in Yrechwydd

against the attack of Owain.

Dunod, lord of the land, planned

to make battle in Yrechwydd

against the attack of Pasgen

Dunod the Stout was son of Pabo the Pillar of Britain who was Arthwys’ uncle. Their Kingdom was in the Pennines called “Dunoting” and was located around modern day Dent and Craven in the Yorkshire Dales and Lancashire. The end of Llywarch’s poem implies that Owain no longer lives after the period of conflict and Dunod was his only named opponent. It would therefore be logical to think that Dunod was responsible for the death of Owain. The death of Dunod is recorded as 595 in the Annales Cambriae. There is evidence that it was actually Dunod and not Owain that died during his raid of Rheged probably in 595. This would support the case that it was in fact Morcant or some other that killed Owain.

In the heartland of Rheged one area was known as “the lands of Llwyvenydd” which corresponds to the modern River Lyvennet valley. Owain is described as the “Prince of glorious Llwyfenydd” in the poetry of Taliesin. In the Lyvennet valley at the picturesque village of Morland there is a sacred well called “Pow Donnet”. A spring emanates from beneath the tangled roots of a large tree.

Morland also boasts the only extant pre-Norman stone church building in the North West of England. Its exact date of construction is unknown but it is generally thought to have been built by Earl Siward of Northumbria in the early 11th century after he conquered this region of the British Kingdom of Strathclyde-Cumbria. However it is equally possible in my view that the church is significantly older and was actually built by Ecgfrith in the 7th century when he inherited rule of Rheged. Ecgfrith (map Rhienmellt map Rhoath map Rhun map Urien) wanted to consolidate his power and claim in the region as he did in Bewcastle and Ruthwell when erecting stone crosses there. He was a renowned church builder which are some of the oldest post-Roman stone buildings in Britain. The stone masonry of St Laurence in Morland resembles both in size and form the masonry of Ecgfrith’s church in Escomb dating to the late 7th century.

In either case, Siward or Ecgfrith, the construction of the church indicates it was a place of high status for the former British kingdom. It is therefore likely that it was also a target for Dunod during his raid on Rheged in the lands of Llwyfenydd. Phythian-Adams and Dr Molly Miller identify the Cumbric place name “Powdonnet” as meaning “Stream of Dunod” referring to Dunod the Stout. They fail to provide an adequate explanation as to why a sacred monument in the heart of Owain’s territory is named after a rival king of a different land. The French Arthurian romance by Chrétien de Troyes “Yvain Knight of the Lion” and the Welsh Romance “Owain Knight of the Fountain” are two versions of the same story based on an older common source. They tell the legendary story of Owain mab Urien as a knight of the Round Table. In both stories Owain journeys from Arthur’s court in Carlisle to a magical fountain in the forest of Brocliande. The fountain has a source emanating beneath a beautiful tree and it causes thunder storms when a libation from it is poured on a nearby stone. Owain initially travels there in order to exact revenge for an attack on his kinsmen at the same location by a Red Knight. Owain proceeds to kill the Red Knight in single combat at the magical fountain, which wins him the hand in marriage of the Lady of the Fountain.

This mythical account of Owain killing a rival at a sacred fountain could be a memory of Owain killing the invader Dunod at the sacred fountain of “Pow Donnet”. This explains its curious name, which probably commemorates the event. Phythian-Adams also makes the case that the bronze age burial cairn on Cardunneth Pike in the North Pennines means “Caer Dunod” except this is unlikely to have any real historical link to Dunod other than a folkloric connection.

In Chrétien’s narrative Yvain sets off from King Arthur’s court in Carlisle to find the magical fountain located in the otherworldly forest of Brocliande. This tells us Brocliande is located in the vicinity of Carlisle in the mind of Chrétien. The otherworldly forest is a common feature of many other Arthurian Romances. It is a motif inspired by early bardic poetry and mythology such as “Battle of the Trees” by Taliesin. A number of these later romances are alternatively set in the royal hunting forest of Inglewood instead of Brocliande. Inglewood Forest is the area roughly between Carlisle and Penrith which not coincidentally is the heart of the historical Owain’s Kingdom. Some of the other Arthurian romances set in Inglewood Forest include: Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle, The Avowing of Arthur, The Marriage of Sir Gawain, Sir Landevale and The Awntyrs off Arthure at the Terne Wathelyne amongst others. These romances are generally known as the Northern Gawain Group.

Many events in these stories occur at Tarn Wadling or “Tarn Gwyddelan” which is Cumbric for “Little Irishman Tarn”. Tarn Wadling is overlooked by “Castel Ewaine” which was a hill fort occupied from the Iron Age until the late Medieval period. It was occupied by the historical Owain mab Urien, hence its name, and is thought to be the castle featured in many of these romances. The tarn has since been drained, the castle demolished and ploughed leaving little remaining evidence of these monuments. Inglewood Forest formed part of the core of Rheged with locations directly associated with the historical Owain possibly serving as the inspiration for Chretians Brocliande. Phythian-Adams notes “For this very area, an intermediate zone of forest waste midway between Carlisle and Penrith - contains a spectacular concentration of mythic British associations” an area which he also notes corresponds to a cluster of Cumbric “Barroc” toponyms. The traditional etymology of Brocliande is the Breton Brech (Hill) + liande (Land) which would translate to Barroc + Llan in Cumbric, another alternative is Broch (badger – a woodland creature) + Llan like at the Roman Fort on Hadrian’s Wall named Brocolitia. It is not inconceivable that the area was previously named something like Breichllan or Brochllan. The area was renamed Inglewood in later centuries when it was settled by Angles which was apparently unusual enough to be noteworthy in the region. This is perhaps another detail that was accurately preserved by Chretian. Even the final stage of Gawain's journey in “Gawain and the Green Knight” is suggested by Sir F. Madden to be Inglewood. Sir Gawain “rode into a deep forest that was wonderfully wild” and after encountering the Green Knight rode with him to his “castle of Hutton” which is thought to be Hutton-in-the-Forest in Inglewood.

The Green Knight as a wild man archetype is a recurring theme in the folklore of Inglewood. In 1420 Andrew Wyntoun wrote the earliest mention of Robin Hood and claimed a link to Inglewood:

Lytil Jhon and Robyne Hude

Wayth-men ware commendyd gude

In Yngil-wode and Barnysdale

Thai oysyd all this tyme thare trawale.

Chretian wrote that Owain was driven mad and lived as a wild man after the Lady of the Fountain loses faith in him. This is a memory also preserved in the triads as Penarwen wife of Owain was remembered as one of the "Three Faithless Wives of Britain". This phase as a mad wildman is also reminiscent of the prophet Myrddin.

William Camden reported in his seventeenth century Britannia that “Ewaine Caesarius” was a knight of “great strength and stature” who used to hunt boars in Inglewood Forest. There is a folkloric tradition in which a giant named Owain Caesarius is buried in a grave in St Andrews Church, Penrith. There is some confusion about the identity of this Owain but it is actually most likely to be a 10th century King of the Cumbrians who was killed at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937. Over the centuries these two Owains have become conflated with one another forming a composite Owain.

The real grave of Owain mab Urien is tangentially connected to his 10th century namesake. In 927 William of Malmesbury recorded that a meeting of Kings occurred at St Andrews Church in Dacre a short distance from Penrith. Owain Caesarius King of Cumbrians hosted Athelstan King of England, Constantine II King of Scotland and Hywel Dda King of Wales at this location of his choosing. The following section will outline my speculative theory about why he chose this place as a royal sanctuary.

Dacre marks the spot of the most intriguing surviving monument to Owain mab Urien. Dacre comes from the Cumbric word “dagr” which means “tear drop” or “trickling one”, which is an apt name for a royal grave site. Bede tells us that it was already a well established monastery in his time relating miracles that occurred here. It is one of only two ecclesiastical sites mentioned by Bede in the land of Rheged, the other being Carlisle. An archaeological investigation of the site has confirmed it was an early medieval cemetery with over 300 graves found dating from the 7th century and probably earlier. They also found the remains of multiple timber buildings and an intricate drainage system built with salvaged Roman stone. Phythian-Adams concludes that Dacre was the site of one of only two British monastic sites in the Kingdom of Rheged, with the other located at Carlisle. The best information we have about the location of Owain’s grave comes from the “Stanzas of the Graves”:

The grave of Owain mab Urien

In a secluded part of the world

Under the sod of Llanforfael

Llanforfael means “The Church of the Great Prince”. There are two possible churches this could be: Carlisle or Dacre. As it is stated that the grave is “In a secluded part of the world” we can rule out the Romano-British city of Carlisle thus “The Church of the Great Prince” must be Dacre. However a second and better translation of the same entry gives us a slightly different rendering:

The grave of Owain mab Urien

In a four square tomb

Under the sod of Llanforfael

Compellingly we find that each of the four corners of the Dacre graveyard are still marked by a mysterious monument forming something of a “four square tomb”.

The monuments are known as the “Dacre Bears”, each of which is an extremely weathered large stone sculpture depicting different forms of a menacing looking creature. Upon closer inspection of two of the sculptures there is a visible long feline tail and mane, which has lead most modern antiquarians to accept them as actually depicting Lions and not Bears.

They have puzzled many over the years but they are commonly accepted to tell a humorous story in four stages: the lion is at first asleep with its head resting on a post; the second lion has a smaller creature attacking it by jumping on its back; the third has the irritated lion swiping at the small creature and the fourth has the lion with a smug face as if he has easily eaten the small creature. I will demonstrate how this story directly relates to Owain mab Urien shortly. The dating of the monument is uncertain but is generally thought to be early medieval. The church itself says “a recently expressed archaeological opinion is that they are pre-Saxon and may originally have marked the boundaries of some pagan sacred site” which would neatly place it in the time of Owain. Each of the Lions appears to have a libation recess cut into to top of its head like some of the Maponus stone heads featured earlier. A brief survey of similar monuments can reinforce the idea that this one is Romano-British or immediately post-Roman British.

There are multiple other instances of similar Lion sculpture monuments nearby which all date to the Romano-British period. The Corpus of Sculpture of the Roman World lists similar examples in Corbridge, Catterick, Carlisle, Cowbridge, Cramond and Kirby Thore. As you can see in the images below the similarities between these monuments are striking. Furthermore their purpose is identical, the Corpus summarises them as “an apotropaic function for guarding a tomb or a funerary enclosure” “with perhaps one at each of the four corners”. This is exactly what we find at Dacre, therefore the Dacre Lions can be confidently dated to the Romano-British period or immediately afterwards which seems to have been the rationale of the archaeologist consulted by the church.

To summarise the theme of the Dacre Lions monument, it depicts a sleeping lion becoming irritated by a small animal which it then kills. This motif is directly referred to in the early bardic poetry of Taliesin in relation to Owain mab Urien at the Battle of Argoed Llwyfain even linking it directly to his grave monument. In the “Death Song of Owain” Taliesin says:

The soul of Owain ab Urien

may the Lord consider its need

the prince of Rheged lies under the heavy green sod

When Owain killed Fflamddwyn

it was no more to him than falling asleep

And in “The Battle of Argoed Llwyfain” Taliesin says:

Fflamddwyn called out again, of great impetuosity,

Will they give hostages? are they ready?

Owain answered, Let the gashing appear,

They will not give, they are not, they are not ready.

And Ceneu, son of Coel, would be an irritated lion

Before he would give a hostage to any one.

In the first poem Taliesin tells us that Owain killed his enemy Fflamddwyn (Flamebearer) with such ease that “it was no more (to him) than falling asleep” which is raised in remembrance after mentioning his grave “under the heavy green sod”. Taliesin also tells us in the dedicated battle poem that Owain was an “irritated lion” relative to his puny enemy “Flamebearer”. So in summary Owain was like an irritated lion killing a small animal with such ease as to be comparable to falling asleep. This is obviously mirrored in the Dacre Lions monument, which means a slight reinterpretation of the monument can be made. The first instalment should be seen as the lion with the small attacking animal on its back, the second as the lion swiping it off, the third easily killing it and lastly the lion falling asleep. In another poem known as "Dinogad's Smock" possibly composed by Aneurin we find the line “as a lion kills an animal”. The poem is set in the Derwennydd River area close by to Dacre about a huntsman catching prey, which further shows that the comparison to fierce lions was a common metaphor at the time of Owain in the same location. Taliesin also gives us more lion metaphors in his poetry such as “The lion will be most implacable”.

In “Yvain, the Knight of the Lion” Chretian tells a similar story linking Owain with lions:

Yvain proceeded through a deep wood, until he heard among the trees a very loud and dismal cry, and he turned in the direction whence it seemed to come. And when he had arrived upon the spot he saw in a cleared space a lion, and a serpent which held him by the tail, burning his hind-quarters with flames of fire.

Yvain slew the flame bearing serpent, which seems to be a parallel to Owain killing Fflamddwyn (Flamebearer). This won him the loyalty and companionship of the pure white otherworldly lion. In the second part of this series I discussed the descent of the royal House of Aberffraw of Gwynedd from the Kings of Rheged. In the “Death Song of Owain Gwynedd” by Cynddelw, Owain mab Urien is mentioned in relation to his killing of Fflamddwyn at the Battle of Argoed Llwyfain. It was Owain Gwynedd’s Son and Grandson Llywelyn the Great who first used the four guardant lions on their royal house arms which was also used by Owain Glyndwr and is still in use as the Royal Badge of Wales today. The House of Aberffraw clearly had knowledge of their roots in Rheged as it was Hywel mab Owain Gwynedd who gives us its accurate location in his poem recounting his journey there. It seems they also knew the link between Owain mab Urien, Lions and the Battle of Argoed Llwyfain and adopted it as their crest.

There is a deeper esoteric link between Owain and Lions as outlined by Sir John Rhys in his book Celtic Heathendom. The Welsh word for lion is “Llew” which in most old Welsh manuscripts was used almost interchangeably with “Lleu”. Lleu was the chief God of the British pantheon equivalent to the Irish “Lugh” or “Lugus” in Gaul. The etymology of “Lleu” is much debated but one common derivation is the root Indo-European word “leuk” meaning “to shine”. It is thought this is also the root of the Irish word “Lug” which means Lynx, because it is a creature with shining eyes. It is very easy therefore to see how the Britons under the influence of Roman culture would come to associate the larger feline Lions with their God Lleu or Llew.

There is a very interesting poem by Taliesin called “Tidings Have Come to Me from Calchvynyd” which tells the story of Owain defending Rheged from a cattle raid. John Koch translates the opening lines as such:

Tidings Have Come to Me from Calchvynyd

disgrace in the Southland, praiseworthy plunder

herds of cattle which the violent one of Lleu's world will give to him.

Other translations of the poem vary and some such as Skene’s change “Lleu” to Lion. This illustrates the difficulty in untethering the God and the creature from each other. Further in the poem Koch gives us the lines:

The manifestation of Mabon from the other-realm,

in the battle where Owain fought for the cattle of his country.

This is clearly equating Owain as an incarnation of another deity called Mabon. Mabon is repeatedly invoked throughout the poem and Rheged itself is referred to as the “land of Mabon”. The poems invocation of Lleu and Mabon seem to equate the two gods together which is the conclusion of historians such as Nikolai Tolstoy. A votive tablet hundreds of years older than the poetry of Taliesin found in sacred well in Gaul called the Chamalieres tablet also equates the Gods Maponus and Lugus together. As well as indicating continuity of tradition this tells us that Mabon is probably an epithet for Lleu. We can conclude from this that Owain incarnating Lleu-Mabon is symbolised as a Lion in his grave monument.

Tolstoy notes that Christ is also equated with Mabon in the poem called “The Rod of Moses” by Taliesin. The Lion headed God of the gnostic demiurge and the Mithraic Arimanius could be easily linked in here but I won’t dwell on that in this article. In Celtic myth Mabon was son of a Goddess called Modron or Matrona. They are archetypes of “divine son” and “divine mother” respectively. This is the same root as terms like “matron” or “maternal”. It is also why “mab” is used to denote “son” e.g. Owain mab Urien and why “Mabinogi” means tales of divine male youth which was applied to both the Bible and Celtic mythology.

The Triads tell us that Modron daughter of Afallach (King of the Otherworld) was married to Urien and was mother to Owain, this again equates Owain as the divine son Mabon. According to a legend recorded in Peniarth 147 Urien came across Modron at a ford where they conceived Owain. John Koch believes this was a sovereignty rite like that recorded in Irish sources relating to the sovereignty Goddess Medb. The sovereignty goddess offered a ritual libation to the King symbolising marrying the deified land, in this case the “land of Mabon” mentioned in Taliesin. Modron became the Morgan le Fay of Arthurian legend who was also said to be married to Urien.

The “land of Mabon” can be confirmed easily by simply surveying the density of Roman inscriptions dedicated to Mabon and Modron. Dedications to these deities both cluster around the western end of Hadrian’s Wall in the land of Rheged. Mabon was a cognate of Apollo according to the interpretatio romana. There were many altars dedicated to Apollo-Maponus some of which depicted the deity with a harp. Lugh (Mabon) was also known as a renowned harpist entertaining the court of Tuatha Dé Danann with these skills.

In the south west of Scotland a toponym that preserves the “land of Mabon” memory is Lochmaben, which was within the Kingdom of Rheged. There is a traditional folk ballad recorded in the Child Ballads (192) called “The Lochmaben Harper”. This interesting cultural artefact seems to preserve a local tradition which was at one time ascribed to the harper deity Mabon. The Lochmaben harper travels to the Kings court in Carlisle. The etymology of the city is itself a reference to the same deity “Fort of Lleu” or “Luguvalium” as the Romans called it. The harper enchants the court of the King with his beautiful songs lulling his audience to sleep. Seizing the opportunity the harper steals the kings horse by tying it to his own and sending them home together. When the king wakes he gifts the harper financial compensation for the loss of his horse from the Kings stables. This tale is also reminiscent of Taliesin who described himself as an enchanting harper “I am a bard, and I am a harper, I am a piper, and I am a crowder. Of seven score musicians the very great enchanter”. He also travelled between courts, although based mainly in Carlisle, obtaining gifts. Taliesin notes that Owain “used to give horses to minstrels”.

Nikolai Tolstoy outlines an account in the “Life of St Samson” about a journey made by the Saints parents in the late 5th century to a temple in the Old North. Samson’s mother couldn’t conceive a child and so the druids of the temple told her to sleep in the sacred enclosure where she had a prophetic dream about her future son. This shrine is identified by Tolstoy as the Clochmabenstane in the Solway Firth near Gretna which was recorded as the “Locus Maponi” cult centre in the Ravenna Cosmography. Apollo-Mabon as the God of healing and prophecy and Modron as the Goddess of Motherhood makes this identification seem extremely plausible. Tolstoy believes the famous Myrddin was a priest of this cult, which we shall briefly return to later in the article. The Clochmabenstane is a neolithic standing stone that seems to have been adopted for use by the local cult.

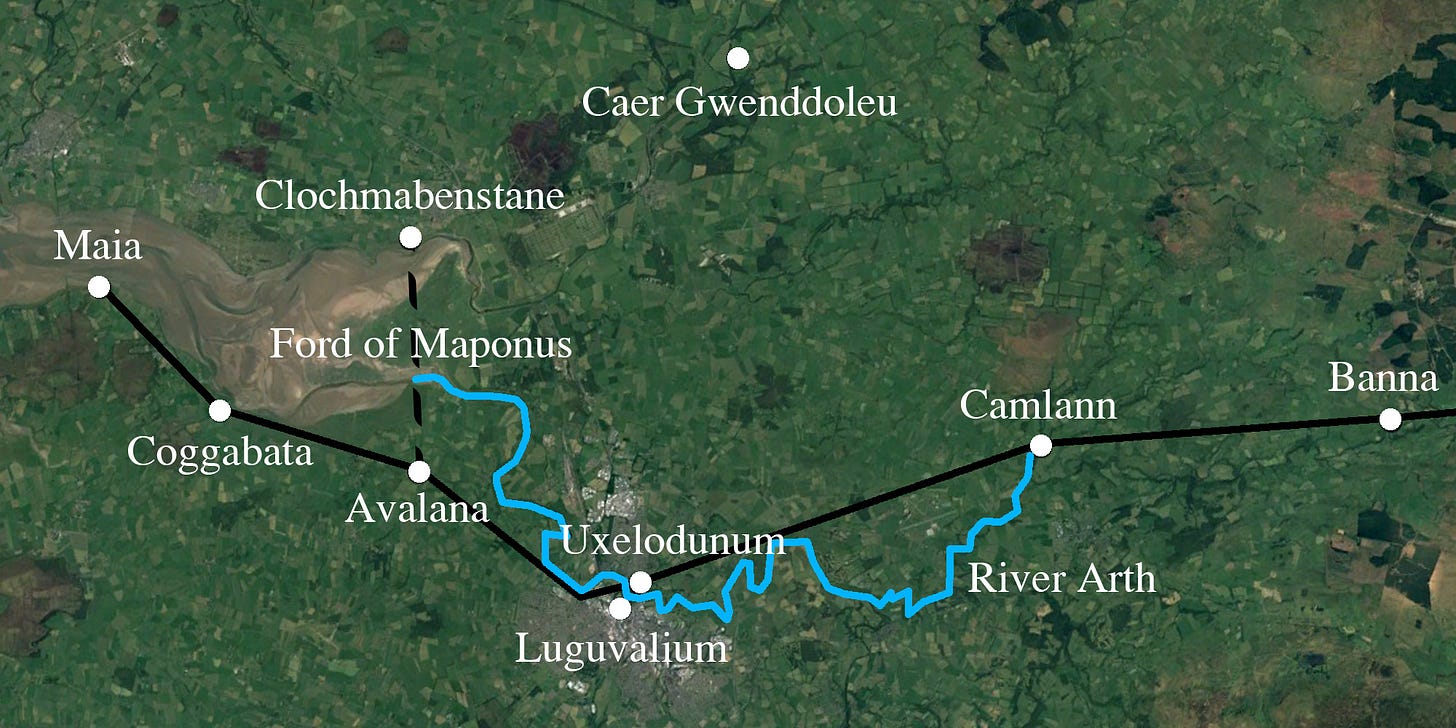

The etymology for the name Solway Firth comes from the Norse word “Sul”, meaning pillar in reference to the Clochmabenstane, and the Norse word “wath” meaning ford. The Sulwath is still the name used for the main ford used to cross the Solway Firth at low tide to this day. If we were to reconstruct the original British equivalent of “Sulwath” we get something like “Ford of the Clochmabenstane” and interestingly enough in the Ravenna Cosmography there is recorded a “Ford of Maponus” which I believe to be the original name used. The Sulwath ford crosses from the Clochmabenstane to Burgh-by-Sands on the southern shoreline. Burgh-by-Sands was originally the third most westerly fort on Hadrian’s Wall called “Aballava”, which was built specifically to guard this popular crossing point. In the Ravenna Cosmography it is recorded as “Avalana”.

Avalon is first briefly mentioned by Geoffrey of Monmouth in Historia Regum Britanniae where “Arthur himself was mortally wounded; and being carried thence to the isle of Avallon to be cured of his wounds” after the battle of “Cambula” against “Modred”. Geoffrey also says Arthur’s sword “Caliburn” was made in Avalon. Geoffrey gives further details in the “Vita Merlini” in a conversation between Merlin and Taliesin about mysterious islands of the world such as Thule. Taliesin goes on to describe Avalon as a bountiful paradise ruled by nine magical sisters with Morgen as their chief. Taliesin says he took Arthur here after the battle of “Camlan” by ship where Morgen received him. Morgen cured Arthur’s wounds on the condition that he stay with her in Avalon. It is from these details that most post-Galfridian accounts of Arthurs end are derived.

The names Avalon, Avalana, Aballava and Afallach derives from the Brythonic “aball” meaning apples. This Isle of Apples is reminiscent of other similar mythical places such as the Hesperides, where the Nymphs guarded divine Golden Apples or the Irish Emain Ablach where the God Lugh spent his youth. In the Welsh manuscripts of Geoffrey “Avalon” is rendered “Afallach”. Afallach was a God, father of Modron and called the “King of Annwn”. Annwn was an otherworld island paradise also said to be ruled by Gwyn ap Nudd (probably another name for Afallach) which can also be identified with Avalon. These incorporeal places are clearly based on religious myth, however this does not exclude the possibility that the historical Arthur was taken to a real place called Avalon after the Battle of Camlann. It may have even been Arthur’s burial in a place called “Avalon” that initiated the words association with the older “Annwn” due to Arthur’s demi-God-like status.

The Battle of Camlann is generally agreed to have been a real historical event that occurred in 537 according to the Annales Cambriae. It occurred following the volcanic winter of 536 as Procopius records “during this year a most dread portent took place. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness... and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse”. I will not rehash the context surrounding Camlann, read Aurochs excellent article for more detail. As Aurochs concludes the battle was most likely a desperate cattle raid on Rheged fought at the Roman Fort of Camboglanna on Hadrians Wall. Aurochs suggests that Medraut ap Letan of Gododdin and possibly the men of Strathclyde joined in a raid of the Coeling Rheged dynasty. Arthwys came to Rheged in support of his kin. This was a long running feud between the two factions recorded in the Yr Gododdin:

In hosts, in hordes, they fought for the land,

With Godebawg's sons, savage folk.

The identity of Medraut has often been tricky as Letan was equated with Llew brother of Urien by Geoffrey of Monmouth which confused things chronologically. Letan’s actual genealogy is recorded in Harleian MS 3859. Arthwys was possibly slain by a warrior fighting for Gododdin called Cydywal ap Sywno according to the Yr Gododdin. I will outline some further evidence that perhaps consolidates Aurochs narrative starting with some simple toponyms to support identification of Camlann as Camboglanna.

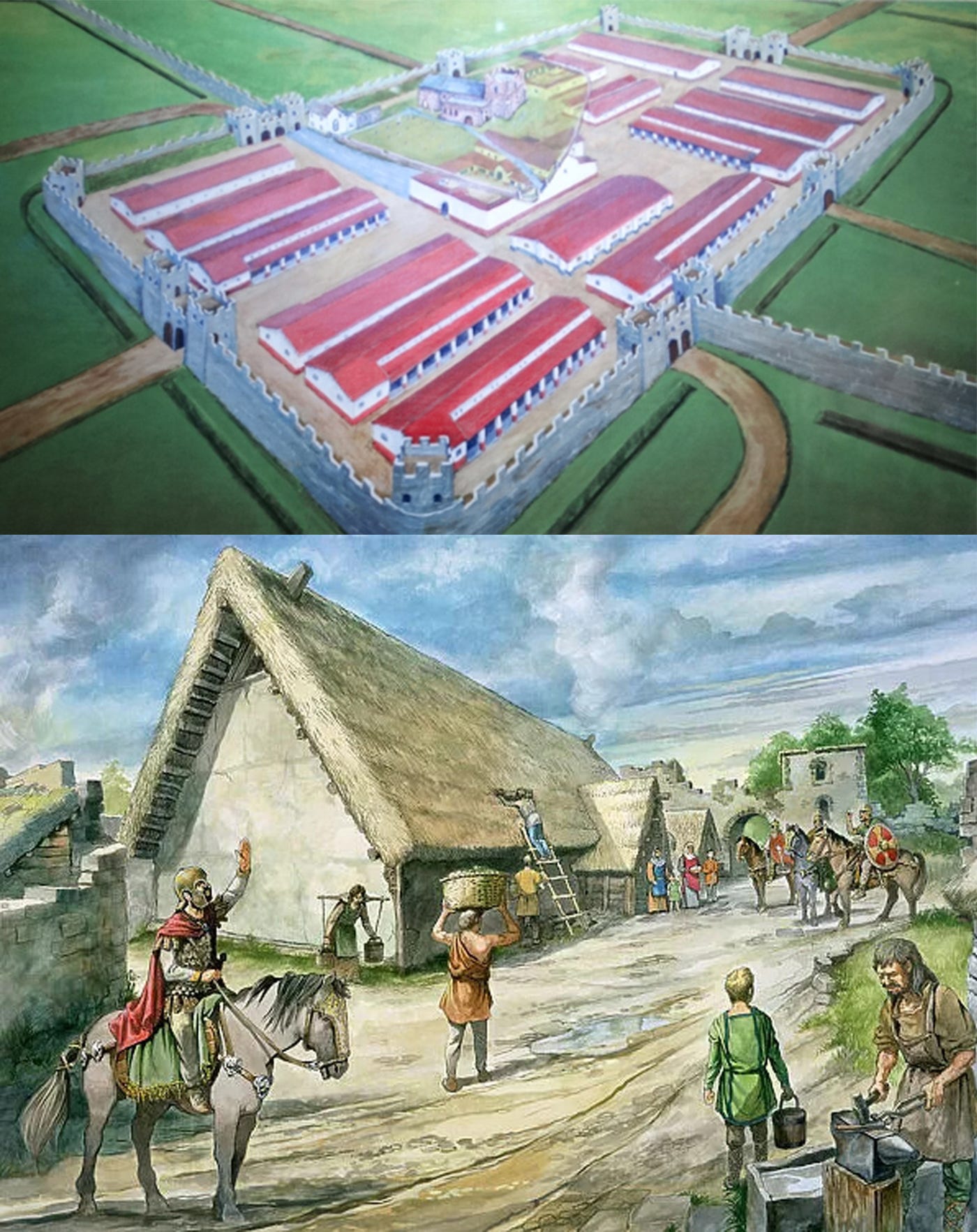

The main court of Rheged was the Romano-British city of Luguvalium (Carlisle). Adjoining the city was the Fort on Hadrian's Wall called Uxelodunum that housed the largest Roman cavalry unit in Brittania. Known as the “Ala Petriana” it was under the direction of a “praefectus” who was himself commanded by the “Dux Britanniarum” (Military Leader of Britain). The Dux Britanniarum was responsible mainly for defence of the northern frontier around Hadrian’s Wall and was based in Ebrauc (York). This seems to perfectly mirror the relationship between Arthwys as Dux Britanniarum in Ebrauc and his cousin Meirchion Gul as praefectus in Luguvalium. Furthermore Uxelodunum was known locally as “Arthur’s burh” in the early 12th century according to a charter of Henry II. This seems to indicate a local memory of the fort having hosted Arthur’s mounted retinue before Camlann. It is for this reason that Carlisle is remembered in many of the medieval romances as the court of Arthur despite it actually being in modern York.

When the approaching invaders were sighted, possibly from the manned fort at Birdoswald, a rapid deployment of cavalry could be made to the very next fort west of Uxelodunum which was Camboglanna. This is where the two hosts clashed and Arthwys was killed. Looking north from Camboglanna there is a cluster of hills several miles away in Kershope Forest that overlook the flat plain in front of the fort and wall. Here we find another toponym possibly commemorating Arthur’s presence called “Arthurs Seat”. However this is a very common place name found all over Britain. Rivers tend to retain names of greater antiquity and so it is of great interest that the Cam Beck flows into the River Irthing less than a kilometre south of Camboglanna. The root of “Irthing” is the Brythonic “Arth” meaning bear according to Andrew Breeze. Geoffrey of Monmouth tells us that after the Battle of Camlann Arthur was transported by Taliesin on a boat to Avalon. The River “Arth” may well attest to an echo of truth in this claim. The River “Arth” does in fact flow from Camboglanna to Avalana after merging with the River Eden and passing through Luguvalium.

Taliesin was a contemporary of Urien and served as Rheged’s court bard recording many interesting snippets of information about different historical events and figures. Urien was born in around 520 so it is possible both of them were present at the Battle of Camlann as young men in 537. It seems unusual that Taliesin the renowned bard wouldn’t have recorded any poems of his own recounting the events of Camlann and transporting Arthwys to Avalana. I believe that three of his most archaic and difficult to interpret poems do exactly this, namely Marwnat Vthyr Pen, Kadeir Teyrnon and Preiddeu Annwn.

The “Marwnat Vthyr Pen” or “Death Song of Uther Pendragon” on first glance doesn’t appear to relate to Arthur but his traditionally attributed father Uther. As Aurochs has comprehensively demonstrated Arthwys was actually a son of Mar and not any Uthyr. There is no Uthyr anywhere in the historical record. It was a characteristic mistake by Geoffrey of Monmouth that first seeded this into the Arthurian canon. One of Geoffrey’s main sources was the Historia Brittonum which according to its earliest version was written by a son of Urien, probably Rhun, and so was relatively close to the historical Arthwys. Two versions of the Historia Brittonum directly state Arthur was called "in British mab Uter, that is in Latin terrible son, because from his youth he was cruel". Geoffrey simply misinterpreted “mab Uter” as “son of Uther” when it was actually an appellation for Arthur himself. This means that all post-Galfridian literature omits Mar as father of Arthwys.

This also means that the references to Uthyr Pen Dragon in pre-Galfridian material is actually referring to Arthur as exemplified in “The Dialogue of Gwyddno Garanhir and Gwyn ap Nudd” where Arthur is called “Arthur uithir” meaning Arthur the Great and Terrible. In the early poem “Pa Gur” Arthur must list his companions where Mabon mab Modron is called the “Servant of Uthr Bendragon” which would only make sense in the context of the poem to be referring to Arthur himself. In a poem by Taliesin called “Death Song of Madog” Madog is referred to as “the son of Uthyr” which means Madog could actually be a son of Arthur. The only Madog in the area frequented by Taliesin in this period is Madog Morfryn father of Myrddin. The only record we have of Myrddins genealogy beyond Madog Morfryn is a record by the “literary forger” Iolo Morganwg who claims Madog is son of Morydd map Mar, brother of Arthwys. The uncertain validity of this reference means that Myrddin could actually be grandson of Arthwys which would explain their close association in later romances. A post-Galfridian poem called “Arthur and the Eagle” has Arthur talking to an eagle in an oak tree about the merits of Christianity. The God Lleu assuming the form of an eagle and sheltering in an oak tree in the Mabinogion is an obvious parallel to this tale. The eagle reveals itself as the son of Madog ap Uthyr, which in my view suggests the eagle could be a disguised Myrddin advising his grandfather from the future. The eagle does refer to itself as nephew of Arthur but this could be another post-Galfridian confusion. A complete analysis of this is beyond the scope of this article.

Returning to the pre-Galfridian “Death Song of Uther Pendragon” by Taliesin we can now read the poem through the lens of “Uthyr Pendragon” as meaning “Great and Terrible Head Dragon” as a title for Arthur. The poem seems to be spoken from the perspective of Arthur in the first section and then switches to the perspective of Taliesin in the second section. I will be stitching together two different translations of the poem from Skene and Haycock to make the most sense of the narrative for our purposes. It does seem to verify Geoffrey’s story that Taliesin was witness to Arthur’s final hours and may be a genuinely ancient account of the event. It further strengthens the identification of Uthyr as Arthur that in the body of the poem “Uthyr” isn’t named anywhere and yet the name “Arthur” does appear as the focus of the eulogy. The poem begins with Arthur exclaiming his virtues:

It is I who commands hosts in battle

I’d not give up between two forces without bloodshed

My ferocity snared my enemy

It is I who’s a leader in darkness

Arthur continues in what I believe is an account of the Battle of Camlann where he died hence the poem:

It is I who defended my sanctuary

in the fight to the death against Casnur’s kin

with vigorous swordstroke against Cawrnur’s sons

The poem them switches to the perspective of Taliesin who says:

I shared my shelter,

a ninth share in Arthur's valour

I broke a hundred forts

I slew a hundred stewards

I bestowed a hundred mantles

I cut off a hundred heads

I gave to an old chief

very great swords of protection

May he be possessed by the ravens and eagle and bird of wrath.

Avagddu came to him with his equal,

When the bands of four men feed between two plains.

The attested presence of “Avagddu” at the battle between two plains is highly significant. In “The Tale of Taliesin” recorded by Elis Gruffydd we learn that “Avagddu” means “Utter Darkness” which was a title given to Morfran ap Ceridwen because of his extreme ugliness. In “Culhwch and Olwen” Morfran is one of the three persons at Arthur's Court who survived the Battle of Camlann because of his ugliness. “No man placed his weapon on him at Camlann, so exceedingly ugly was he; all thought he was a devil helping. There was hair on him like the hair of a stag”. The strong association of Avagddu with the Battle of Camlann confirms that the “Death Song of Uthyr Pen Dragon” is about Arthur at Camlann. We will discuss other relevant lines of this poem when most relevant including the line about Arthurs opponents “Cawrnur’s sons” after the next poem.

The next poem by Taliesin that I believe also recounts the “Battle of Camlann” is called “Kadeir Teyrnon” or “Chair of the Famous Lord”. This poem is extremely archaic and as such is notoriously difficult to translate and interpret however Haycock shares my belief that it is fundamentally a poem about Arthur. The poem opens by teasing the identity of the poems focus before it is revealed to be Arthur:

concerning a man, a brave authoritative one

from the stock of Aladur

and his red armour

and his host attacking over the rampart

in the midst of a lordly warband

He bore off from Cawrnur

pale harnessed horses

After teasing the identity of the lord and listing his virtues and feats of war the identity of the lord is revealed:

The sovereign elder

The generous feeder

The third deep wise one

To bless Arthur

Arthur the blessed

a defence in battle

trampling nine at a time

Taliesin then recounts his bardic skill and the generosity of the lords that have hosted him before vaunting his knowledge by posing a series of challenging questions:

What are the names of the three fortresses

between the sea flood and the low water mark?

He who’s not ardent doesn’t know

There are four fortresses

in the havens of Britain

tumult of lords

After this Taliesin voices anxieties about foreign invasions from the sea, perhaps in reference to the amassing numbers of Angles arriving and settling:

There will be fleets

The wave washes over the shingle

certain to be the realm of the sea

neither slopes nor a sheltered spot

nor hill nor hollow

nor a covering from the storm will there be

in the face of the angry wind

Taliesin then seems to lament the death of Arthur:

I assume a sad manner

as a result of the annihilation of the lord

with a fiery nature

Taliesin then perhaps eulogises Arthur’s rise to prominence around the area of Hadrian’s Wall:

From the loricated Legion

Arose the lord

Around the old renowned boundary

Taliesin concludes with more anxieties about the future in reference to the Angles which tells us about the sentiments in the court of Rheged before Uriens own rise to prominence:

The foreign peoples

are a fast flood

of sea-voyagers.

There is a lot of information that can be extracted from this intriguing poem. Firstly it confirms that Arthur was seen as a great warrior king and military commander possibly operating in the Hadrian’s Wall region which confirms the idea of Arthur as essentially a continuation of the “Dux Britanniarum”. It also states he is “from the stock of Aladur” which is a reference to the Romano-British God of war Mars-Alator. This probably just means Arthwys was a warlike king but could also be a poetic allusion to being son of “Mar”.

We will deal with Taliesin’s question of fortification knowledge later. Taliesin portrays Arthur as having conducted a daring raid to steal horses from a rival named “Cawrnur”. This is a repetition of the enemy found in “Marwnat Vthyr Pen” in which Taliesin portrays Arthur saying: “It is I who defended my sanctuary” “with vigorous swordstroke against Cawrnur’s sons”. Firstly this confirms both poems are talking about Arthur, but furthermore it confirms that he probably died fighting this enemy “Cawrnur’s sons” at Camlann. The identification of this enemy is a relatively simple one. Caw of Prydyn was a famous Pictish King in the Old North who conquered the Kingdom of Strathclyde in the late 5th century. Caw was famous for reputedly having twenty four sons including the bard Aneurin who composed “Yr Gododdin”, the famous Gildas and a famous warrior king named Hueil. In the “Life of Gildas” the Saint is called son of “Caunus” which seems to be a variation of the “Casnur” used in “Marwnat Vthyr Pen” as another name for Caw or “Cawrnur” of Prydyn. Aneurin ap Caw also gives us the earliest reference to Arthur (alongside Taliesin) and alludes to conflicts between the more northern kingdoms and the Coeling. This identification of “Cawrnur’s sons” is very interesting for a number of reasons, later legendary accounts hold Caw and his son Hueil as traditional enemies of King Arthur.

It is mentioned in “Culwch and Olwen” that Hueil ap Caw never “submitted to a lord's hand” and that he stabbed Arthurs nephew causing a feud between the two of them. Hueil is also mentioned as one of the “Three front leaders of battle” in the triads. In the Breton “Life of Gildas” it says Hueil was “a very active man in war, who, after his father's death succeeded him to the throne”. In the “Life of Gildas” by Caradog of Llancarfan it is confirmed he is the oldest of Caw’s sons. It also tells us that “Hueil, the elder brother, an active warrior and most distinguished soldier, submitted to no king, not even to Arthur. He used to harass the latter, and to provoke the greatest anger between them both. He would often swoop down from Scotland, set up conflagrations, and carry off spoils with victory and renown”. Arthur eventually killed him during one of these raids.

Elis Gruffydd tells a more humorous version of events. Hueil “obtained possession of one of Arthur's mistresses”. This caused Hueil to injure Arthurs knee in combat over the affair. Arthur agreed to leave Hueil in peace but later he crept back into Hueils court dressed in women's clothes to spy on a girl:

“Huail chanced to come there, and he recognized Arthur by his lameness, as he was dancing in a company of girls. These were his words: This dancing were all right if it were not for the knee”.

Arthur beheaded Hueil on a stone for this insult. Tradition says this stone can be seen in the marketplace of Ruthin, Denbighshire to this day.

A saying is attributed to Hueil in the “Sayings of the Wise Men” that “Often will a curse fall from the bosom”. This could be a reference to his fight with Arthur over “one of Arthur's mistresses”. It has always puzzled historians how Gildas can omit any mention of the historical King Arthur in his writings when they were contemporaries. In the “Life of Gildas” by Caradog it says that after hearing that Arthur had killed Gildas’ brother Hueil that “he was grieved at hearing the news, wept with lamentation”. Giraldus Cambrensis claims Gildas destroyed "a number of outstanding books" about Arthur after hearing of the death of his brother which would explain why there is no mention of Arthur in his works. Gildas also set up a monastery over the grave of his father Caw at a place in Strathclyde called “Cambuslang” which could offer an alternative location for the Battle of Camlann, however Camboglanna is still preferred in my view.

As Aurochs has previously mentioned Medraut ap Letan of Gododdin married Cywllog, a daughter of the northern king Caw. This could mean that Medraut was allies with “Cawrnur’s son” Hueil at the Battle of Camlann. The “Life of Gildas” by Caradog has another tale about a wicked king called “Melwas” who violated and abducted Arthur’s wife Gwenhwyfar. Melwas and Medraut can be identified as the same person which is interesting as then both Hueil and Medraut are reputed to have abducted Arthur’s consort. Gwenhwyfar is often cited as being involved in the instigation of Camlann in other sources such as the triads which states Medraut “dragged Gwenhwyfar from her royal chair, and then he struck a blow upon her”.

From all the analysis above a narrative of Camlann can be reconstructed. In the wake of the volcanic winter of 536 a series of raids occurred between the Coeling and the more northerly kingdoms of Strathclyde, Gododdin and Pictland. Arthwys himself “bore off from Cawrnur, pale harnessed horses”. In response women and cattle were abducted by “Cawrnur’s sons” and Medraut. This caused great anger amongst the Coeling who mustered a great host combining the forces of Arthwys and Rheged. Anticipating another raid the Coeling ambushed a combined force from Strathclyde, Gododdin and Pictland. This is “when the bands of four men feed between two plains” at Camboglanna. The four men were Dux Bellorum Arthwys Uthyr Pendragon allied with Meirchion the Lean of Rheged (With Urien and Taliesin in his host) fighting against “Cawrnur’s sons” lead by King Hueil ap Caw who was allied with Medraut ap Letan of Gododdin. This is when Arthwys:

“and his host attacking over the rampart”

“trampling nine at a time”

“in the fight to the death against Casnur’s kin”

“with vigorous swordstroke against Cawrnur’s sons”

Arthwys was slain by a warrior from Gwynedd fighting for Gododdin called Cydywal ap Swyno. There were very few survivors of this battle with perhaps every King dying in action. A pyrrhic victory for the Coeling. After the battle, Arthwys (and probably Meirchion) were transported west by barge on the River “Arth” to the Fort of Avalana for burial. This was conducted by a party including a young Taliesin and probably the new young King Urien as well as probably the new King Eliffer ap Arthwys who inherited command of his “Great Warband”. In the next section I will look at evidence that reinforces the identification of “Aballava” or “Avalana” with the legendary Avalon.

The first piece of supporting evidence for the identification of the Roman Fort Aballava as Geoffrey’s legendary Avalon is the previously mentioned record in the Ravenna Cosmography calling it “Avalana”. Secondly the geographical context supports the theory. The western end of Hadrian’s Wall was commanded from Luguvalium. The first fort to the east of Luguvalium is Camboglanna, the site of Camlann. The first fort to the west of Luguvalium is Avalana. Both forts are connected by the River “Arth”. The bard Taliesin has been demonstrated to have been present at Camlann and was said by Geoffrey to be the one transporting Arthur to Avalana by barge. Taliesin was the bard to Rheged which held court in none other than Luguvalium exactly between Camboglanna and Avalana.

A “Breton Lay” called “Sir Landevale” was recorded by Marie de France in the 1170s and so narrowly post-Galfridian. The original source was supposedly Breton bardic folklore. It preserves what could be a separate tradition to that of Geoffrey of Monmouth. A knight called Sir Landevale falls into debt and leaves Arthur’s court in Carlisle. Riding west Sir Landevale comes across a naked fairy who was the daughter of the King of Avalon. After falling in love and concluding the rest of the tale Sir Landevale and the fairy princess move to the Isle of Avalon together. This tale seems to be a retelling of Urien conceiving Owain at a stream with the Pagan Goddess Modron daughter of Afallach. Although the important piece of information that it preserves is the directions to Avalon to the west of Carlisle, which is exactly the location of the Fort of Avalana.

There is a reference to the burial of Arthur in the triad “Three Men of Shame were in the Island of Britain” which says simply that he was “buried in a hall on the Island of Afallach”. This as far as I know is the only source that confirms Arthur was actually buried in a place called Afallach or Avalon. His grave is also mentioned in the “Stanzas of the Graves” as "a wonder of the world is the grave of Arthur". Other translations differ but this could be a reference to Hadrian’s Wall itself, of which the Fort of Avalana was a part.

In the early 14th century King Edward I temporarily based his court in Carlisle whilst he was campaigning in Scotland. Edward is known to have modelled himself on the image of King Arthur. He tried to become High King of all Britain with extensive campaigns in Wales and Scotland. He even constructed a round table for himself which can still be seen in Winchester today. It is probable that whilst holding court in Carlisle he was regaled with the local tales of King Arthur and Avalon. In the summer of 1307 Edward caught dysentery and died. However it is curious that he didn’t die comfortably in Carlisle Castle, instead he chose to travel west to the Fort of Avalana where he died on the Sul Wath (Or Ford of Maponus). He was laid to rest in St Michaels Church which sits within the site of the old Roman fort. Perhaps Edward heard tales of Avalana and chose to emulate Arthur even in death hence his puzzling journey.

The Taliesin poem “Kadeir Teyrnon” that we analysed earlier contains details of Arthurs life and death. In a section of the poem Taliesin poses a challenge testing the audiences knowledge of presumably local fortifications saying:

What are the names of the three fortresses

between the sea flood and the low water mark?

He who’s not ardent doesn’t know

There are four fortresses

in the havens of Britain

tumult of lords

I believe these seven forts comprise those under the control of Rheged from Luguvalium at the western end of Hadrian’s Wall. From West to East: Maia, Coggabata, Aballava, Uxelodunum, Luguvalium, Camboglanna and Banna. These were probably the forts within the old Roman Civitas Carvetti which corresponds roughly to modern day Cumbria. These forts are also commonly grouped together in souvenir bowl artefacts such as the Rudge Cup and the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan.

The three forts “between the sea flood and the low water mark” are Maia, Coggabata, Aballava which are all situated in a low lying coastal marsh that frequently floods during high tides. This is probably why Avalana is often referred to as an island. The remaining four forts “in the havens of Britain” are Uxelodunum, Luguvalium, Camboglanna and Banna. Taliesin notes after the four forts about a “tumult of lords” which is probably a reference to the battle at Camboglanna. It is highly significant that Taliesin makes allusions to both Camboglanna and Avalana in a poem about Arthurs life and death. There is a third and final poem Taliesin composed about Arthur with a more mystical tone.

The archaic poem “Preiddeu Annwfn” was Taliesin’s attempt to mythologise his first hand account of Arthurs final passage to the Otherworld. It is fair to say he successfully enchanted Western Culture for millennia with his inspired work. It recounts a voyage to the Otherworld Annwfn by Arthur and his warriors. The major theme seems to be Taliesin's sadness at Arthurs passing, variations of “And when we went with Arthur, sad journey” are repeated throughout the poem which ends with “may I not endure sadness”. Arthurs physical burial in Avalana was conflated with Taliesin's account of his passing to Annwfn which is why the term Avalon became simply another name for the otherworld. The poem may also contain an intellectual attack on Gildas with Taliesin repeatedly attacking men of the church with such lines as “I don’t rate the pathetic men involved with religious writings”. It seems he had a disdain for those who complain without taking action “pathetic men with their trailing shields, with no go in them”. Taliesin says that of the many men that accompanied Arthur on his raid only seven returned which is perhaps a reflection of the Battle of Camlann itself. Taliesin describes seven different forts in the otherworld, although these seven forts are thought to symbolise the ascent through the seven heavens or celestial bodies, knowledge of which Taliesin displays in his “Song of the Macrocosm”.

The poem is also credited as the beginning of the grail legend. Arthur and his warriors are targeting the King of Annwfn’s cauldron which was “kindled by the breath of nine maidens”. Modron is the leader of the nine sisters who became the Morgan le Fay and nine sorceresses of the later romances. On the opposite side of the Ford of Maponus to Avalana is the Clochmabenstane, which according to old surveys used to be a Neolithic stone circle comprised of nine stones. Stone circles around Britain are often equated with the Nine Maidens even today. Perhaps at one time ritual processions occurred from Avalana down the Ford of Maponus to the circle of Mabon and Modron. This is just speculative however the Roman Historian Procopius describes Britain as divided by a great wall that is a lush paradise to the south and a land of the dead to the north:

“the inhabitants say that if a man crosses this wall and goes to the other side, he dies straight away. They say, then, that the souls of men who die are always conveyed to this place”

There is no better place than the Ford of Maponus for the souls of the dead to make this crossing. It is also interesting that in the romances both Cai and Peredur must kill the nine sorceresses. The historical Cai (Ceidaw ap Arthwys) and Peredur (Peredur ap Eliffer ap Arthwys) both had involvements in the “land of Mabon” region of south west Scotland. The Battle of Arthuret was fought over religious practises according to one tradition. According to Tolstoy, Myrddin was a priest of this cult.

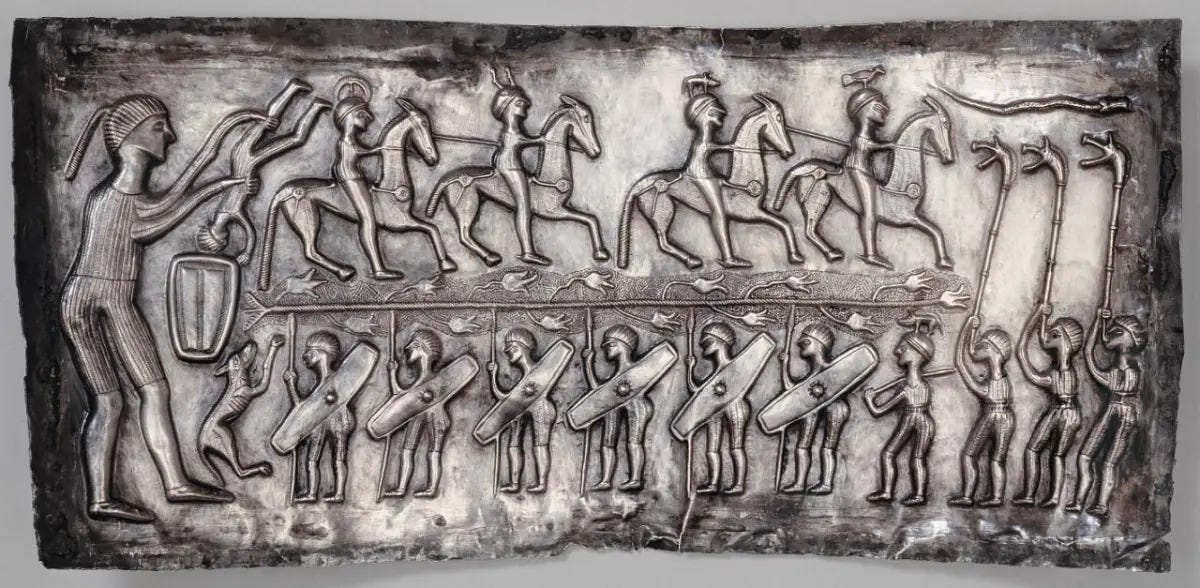

In this article I won’t do a deep dive on the grail motif however I will briefly cover the link to the Celtic “Severed Head Cult”. The otherworld cauldron referred to by Taliesin is frequently referred to elsewhere in Celtic mythology. A depiction of the Gundestrup Cauldron shows warriors being reincarnated after getting dunked in a cauldron by a God.

In the Mabinogion tale “Branwen” the God King Bran (“Bran” means Raven) has a magical cauldron that rebirths warriors. At the end of the tale the cauldron is destroyed and Bran is mortally wounded. He commands his men to decapitate him and bury it under the Tower of London. After feasting for seven years with the head they bury it facing France to protect from foreign invasion. Ravens have been kept there ever since. Winston Churchill even ensured the “unkindness” of Ravens was fully stocked during WW2. It was reported that during a visit to the Tower in 2003, the Ravens spooked Vladmir Putin by saying “Good Morning!” to him. According to the triads “Arthur disclosed the Head of Bran the Blessed from the White Hill, because it did not seem right to him that this Island should be defended by the strength of anyone, but by his own”.

In the earliest Arthurian romances that feature the grail it is guarded by the “Fisher King” sometimes called “Bron” which is an allusion to Bran. In the French romance “Perceval, the Story of the Grail” the hero receives the grail whereas in the Welsh equivalent romance “Peredur son of Efrawg” the hero instead receives a severed human head in place of the grail. Another extremely common manifestation occurs throughout the romances which is known as the “beheading game” such as that in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It is thought that when the warrior submits to receiving the decapitating blow he undergoes a symbolic death and rebirth. These cultural artefacts date back to the practices of the ancient celts who were known by classical writers to revere the head as the seat of the soul. As Tolstoy points out there was a custom at the festival of Lughnasa of taking a carved stone God head from its sanctuary and placing it on top of a hill for the duration of the festival. It is for this reason carved stone heads of deities are one of the most common artefacts found in Celtic regions. There are large numbers of these artefacts found in the Old North, those found in the Rheged and Hadrian’s Wall area are thought to depict Mabon. Llywarch’s account of decapitating Urien after his death and carrying his head back to the “land of Mabon” is probably evidence of similar beliefs flourishing in the time of Arthur “A head I bear by my side,

The head of Urien, the mild leader of his army”. Perhaps the head of the sovereign symbolised the soul of the kingdom which must be rebirthed through the divine mother (Modron) and divine son (Mabon).

This brings us to our next monument of intrigue. If Taliesin really did bring Arthwys to one of “the three fortresses between the sea flood and the low water mark” and was subsequently “buried in a hall on the Island of Afallach” then perhaps there remains a monument to Arthwys at the Fort of Avalana as we find for Owain at Dacre. The obvious place to start looking is the fortified St Michaels Church, Burgh-by-Sands which sits on the site of the old Fort of Avalana built with repurposed Roman stone. Specifically it sits over the Roman granary building which is interesting as at the Fort of Banna (Birdoswald), also controlled by Rheged, archaeological investigations have found the remains of two post-Roman 6th century large timber halls over the granary buildings. Perhaps the “hall on the Island of Afallach” was a large timber hall built on the granary at Avalana by the same builders for the same reasons as the hall at Banna.

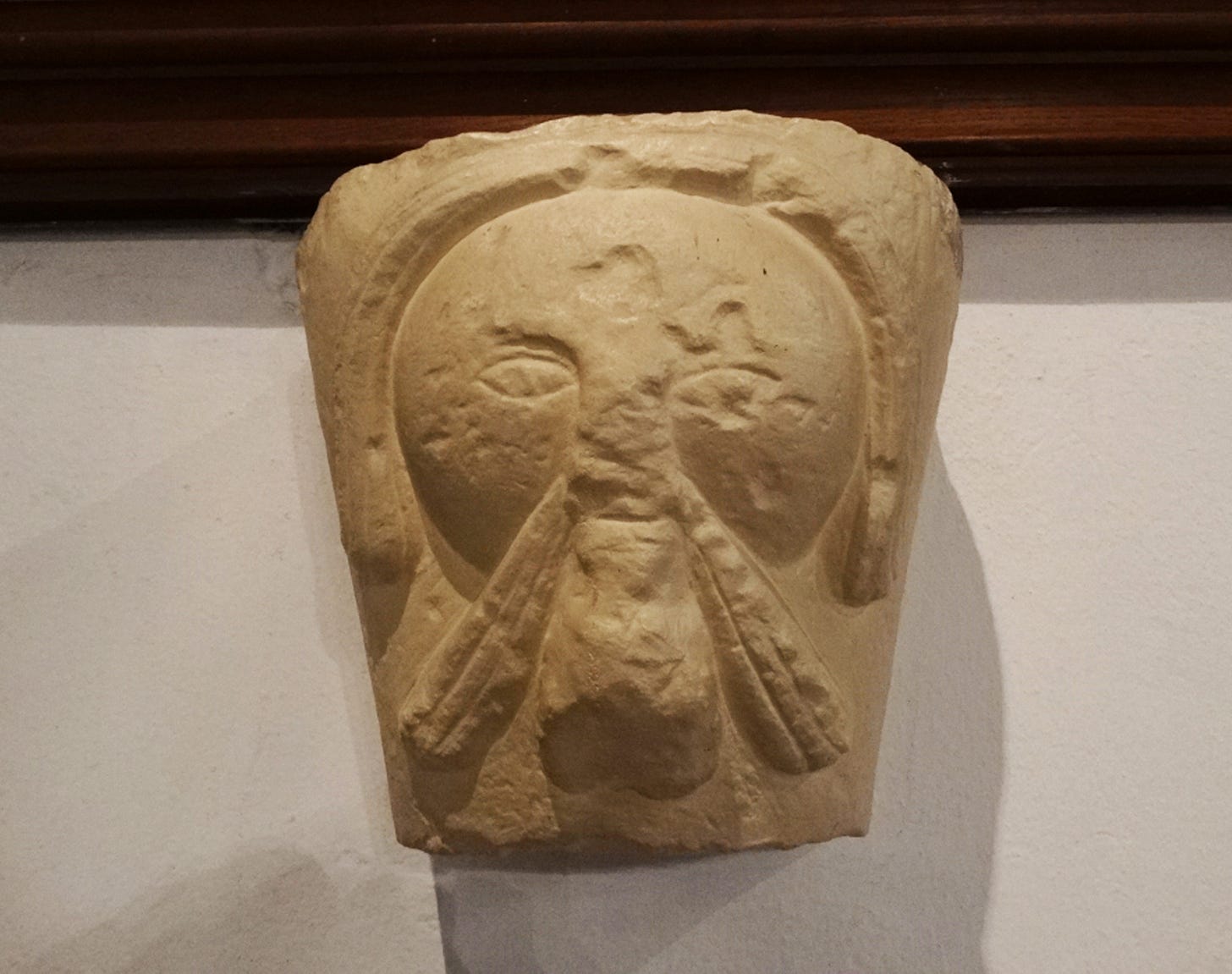

The church dates to the Norman period but is thought to have been built on top of older structures. Perhaps even directly on top of the “hall on the Island of Afallach”. Inside the church we find a number of monuments that according to Pevsner pre-date the Norman Church itself. The first of these is a carved Romano-British stone head depicting some God-King complete with distinctive unshaven top lip characteristic of this type of votive stone head. It is situated prominently above the altar. There is some disagreement about its date with some sources saying it is Norman but I agree with Pevsner that it is a repurposed Romano-British object. Perhaps at one time this head was repurposed to commemorate Arthwys or maybe it is even a depiction of Arthwys himself.

The second monument of interest inside the church is also of contested date and origin, some sources say Norman and some say it is earlier and Anglo-Saxon. To my mind this simply means it is of uncertain early medieval origin and thus open for speculation. They both seem to match the style of other early medieval artwork featuring the same subjects. Two pieces of stone masonry used to build the undercroft depict animal carvings which both, perhaps coincidentally, feature animals prominently associated with Arthwys. There is no consensus as to what the first animal is, but to my eyes it looks very much like a bear. The name “Arthwys” is of course derived from the Brythonic word for bear “Arth”. The association here with Arthur is obvious. The second animal depicts a large bird, probably a raven. Ravens were intimately associated with passing over into death in the British Heroic Age. In the Taliesin poem “Death Song of Uther Pendragon” which we earlier deciphered as a eulogy to Arthur’s death at Camlann we find the line “May he be possessed by the ravens and eagle and bird of wrath”. Throughout Britain there has long been folkloric superstitions associating King Arthur with the Corvid family of birds summarised in the Spanish novel “Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes “there is an ancient tradition, generally believed all over Great-Britain, that he did not die, but was, by the art of enchantment, metamorphosed into a raven”, perhaps we have found the source of this belief in Taliesin's poetry. The reference to Arthur in the Yr Gododdin also does so in relation to Corvids “He brought black crows to a fort's Wall, though he was not Arthur”.

While the God-King stone head and the animal carvings could easily be nothing to do with Arthwys whatsoever, if you were to imagine artefacts adorning his shrine these wouldn’t be far off the mark. Even if they both post-date the time of Arthwys, they may be preserving an older memory.

The sovereign elder

The generous feeder

The third deep wise one

To bless Arthur

Arthur the blessed

Absolutely wonderful article. I hope that these articles are someday combined in book form as companion pieces to Aurochs' upcoming published work.

I feel the need to thank you both for your continued excellent scholarship & detective work. My dips into Taliesin etc have mosty made my brain hurt.

We're back in The Old North for our holz in a few weeks time on the Tweed but now feel the urge to drive down the A69 to go on a pilgrimage tour to Avalon to via Camlan.