Here is part two of p5ych0p0mp’s deep dive into the history of Rheged. Princes, Pirates, Pirate Princes, Ireland, genealogies, and speculation all present. Wonderful stuff to be had here, and fantastic research. Give it a read!

Part Two: Pirate Princes of Rheged

In Part One of this series we analysed the sequence of events in the rise and fall of the Kingdom of Rheged. This article will outline a possible survival of a branch of the Rheged dynasty through Pasgen ap Urien. In Part One it was demonstrated that the critical turning point for Rheged was Ecgfrith son of Oswy inheriting Rheged through his mother Rheinmellt ferch Rhoath. We will see a convergence onto Ecgfrith in this article as well however we will construct our argument in a reverse chronological order starting in the 9th century Kingdom of Gwynedd.

Merfyn Frych was the first king of Gwynedd not descended from the famed Cunedda. He took the throne through his mother Essylt, daughter of King Cynan ap Rhodri. It was after the death of Cynan's brother Hywel ap Rhodri, that the last male descendent of Cunedda was extinguished. Earlier Hywel was banished from Anglesey by his brother Cynan in a dispute over Kingship, consequently Merfyn hosted him on The Isle of Man. According to the “Cronica Walliae” Hywel enjoyed land on the Isle of Man and "other lands in the North" for five years until his death. It is unspecific where these "other lands in the North" were located. Merfyn's father was Gwriad ap Elidyr of Manaw (Isle of Man). As Merfyn inherited the throne of Gwynedd matrilineally there is scant information about his father Gwriad. His patrilineal origins are thus unclear.

According to genealogies from Jesus College MS 20 Gwriad ap Elidyr is traditionally ascribed descent from prominent northern figure Llywarch Hen:

Merfyn Frych ap Gwriad ap Elidyr ap Sandde ap Alcwn ap Teged ap Gweir ap Dwc ap Llywarch Hen ap Elidyr Lydanwyn ap Meirchion Gul ap Gwrwst Ledlum ap Ceneu ap Coel Hen

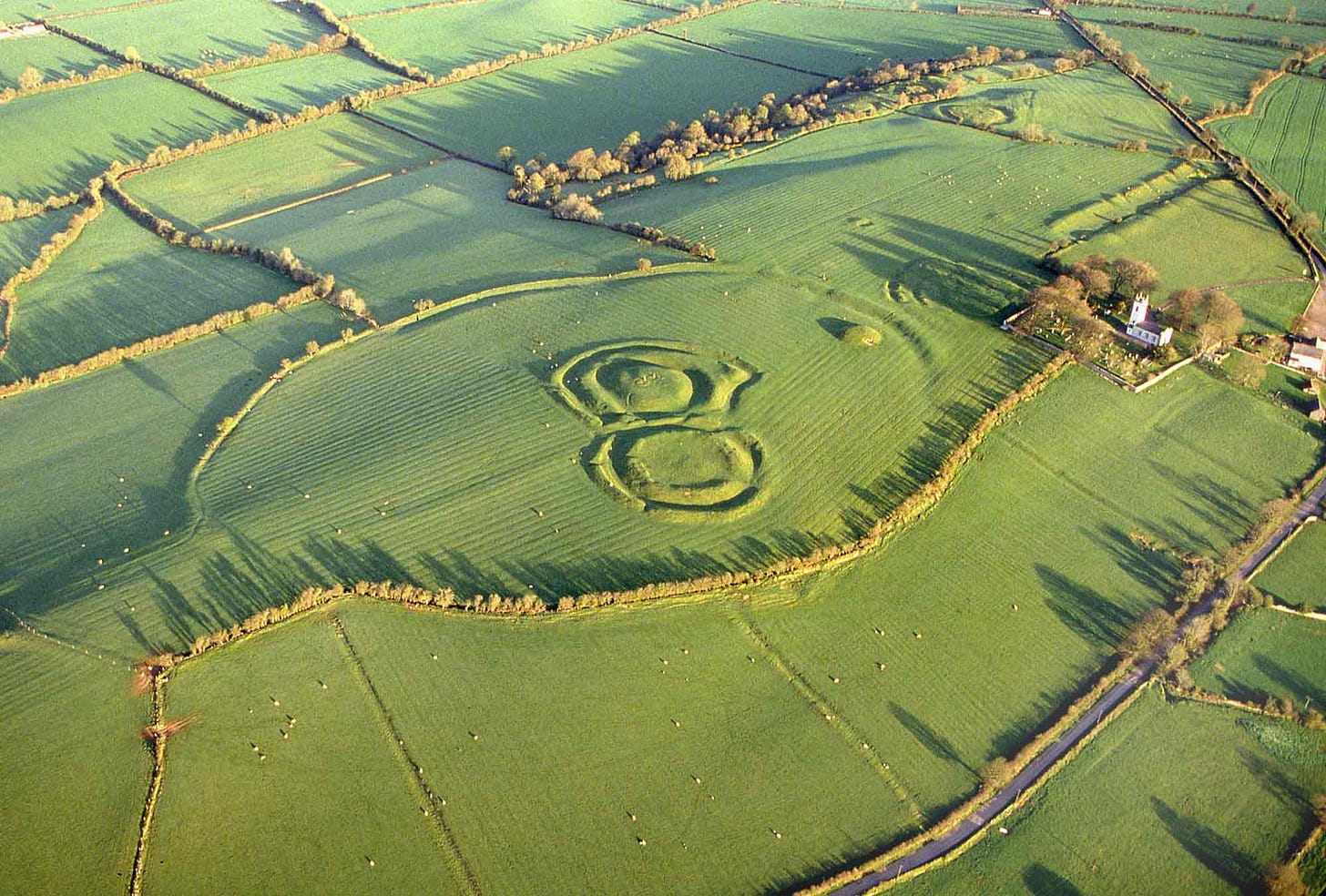

An inscribed Brythonic "Cross of Gwriad" was found on the Isle of Man dating to the correct period confirming that Gwriad ap Elidyr belonged to an elite Brythonic dynasty on Manaw. The cross was found on the eastern extreme of the island at Maughold, directly opposite the Cumbrian coast and an old hill fort called Caernarvon, which translates roughly as "Fort overlooking the island". Caernarvon, near Beckermet, is the closest point of the mainland as the crow flies for journeying from the old kingdom of Rheged to Ynys Manaw (Isle of Man). Caernarvon lies on the old Roman road to the nearby Roman port of Ravenglass. In folklore Ravenglass is reputedly home to the faery King Afallach, who oversaw passage to the other worldly western island of Avalon. It is reasonable to assume from the geographical context and the mytho-poetic parallel that frequent trips were undertaken between Caernarvon-Ravenglass and Ynys Manaw.

As an interesting aside, near Caernarvon an ancient cross in St Bridget's Church, Beckermet has a strikingly similar appearance to the Pillar of Eliseg in Wales. The inscription reads: “H[I]N[-]LE[D-E] IUDI[I-D.H] *[-N]IET *O[-..]E [.]X[-]”. At present this text has not been deciphered, nor has the language in which it was written been determined. It dates to the same period as the Pillar of Eliseg and the Cross of Gwriad. The Pillar of Eliseg was erected by Cyngen ap Cadell, the King of Powys. Merfyn Frych had good relations with his neighbour Cyngen ap Cadell, he was married to his sister Nest. An interesting Hiberno-Latin text known as the Bamberg cryptogram, written in Merfyn's court, also reveals "Merfyn the king greets Cyngen", which confirms the close relationship between the two kings and allies. It is very possible Cyngen and Merfyn patronised the same mason by commissioning stone crosses in similar styles: The Pillar of Eliseg and the Beckermet Cross respectively, this may explain their similar appearance. It may be that the Beckermet Cross reveals Merfyn's aforementioned "other lands in the North" beyond the Isle of Man. This is of course rampant speculation and until the Beckermet Cross inscription is deciphered we may never know.

However we do know that in the 9th century, Northumbrian power was waning on this western edge, which lead to its eventual annexation by the British Kingdom of Strathclyde into a greater "Cumbraland". It is certainly possible at this time that Merfyn could have projected his power from the nearby Isle of Man to reclaim rule of his ancestors territory around Caernarvon. The Historia Brittonum says that Caernarfon in Gwynedd was also called “Mirmantun”. This alternate name stands for “Merfyn's Town”. This connection of Merfyn to Caenarfon in Gwynedd, perhaps suggests that the parallel Caenarvon in Cumbria was “Merfyn's Town” too. Both fortifications were strategic outposts overlooking his core territory on the Isle of Man.

Putting the Beckermet Cross speculation to one side, the Cross of Gwriad definitively attests to the presence of Brythonic elite settlement on the Isle of Man, a dynasty probably stretching back to the old kingdom of Rheged given Gwriad's supposed descent from Llywarch Hen, a known warrior and bard of Rheged. The Irish sea was a convenient and well used corridor of travel for Britons of the period, and so seeking refuge on the Isle of Man or in Ireland is certainly feasible for a late 7th century elite retreating west. A confirmed example of exactly this tactic is Cadwallon ap Cadfan who retreated to Ireland when besieged by Edwin only to later return and conquer. Evidence of a late 7th early 8th century British war band fleeing west during the reign and expansion of Ecgfrith into Rheged is found in the Annals of Ulster (Years 682, 697, 702, 703 & 709). These Britons were repeatedly raiding Ireland which many scholars directly link to expelled British Princes from Rheged. I will discuss this in more detail later.

By 685, the year of Ecgfrith’s death, the capital of Rheged was in Northumbrian hands when Cuthbert visited the Romano-British city of Carlisle to marvel at its impressive structures and see Ecgfrith’s wife Iurminburh. It is during the reign of Ecgfrith that rule of Rheged seems to have passed from the last recorded King Rhoath ap Rhun, grandson of Urien Rheged, to Ecgfrith. Probably inherited through his father Oswy's marriage to Rhoath's daughter Rhienmellt, as discussed in Part One of this series. This seemingly peaceful accession of power was probably viewed negatively by a faction of the Rheged elite who weren’t comfortable with what they likely viewed as an Angle interloper as ruler. It is this faction that likely fled west to the Isle of Man and Ireland during Ecgfrith’s reign at some point around or before 670. After Ecgfrith’s death in 685 at the hands of the Picts, Northumbrian expansion ceased and in some cases reversed. This halted westward expansion could have allowed an exiled Rheged elite to cling to power in their small island kingdom to freely raid Ireland as recorded in the Annals of Ulster. This remnant Rheged elite eventually culminating in Merfyn ap Gwriad.

There is however a few problems with Merfyn's uncertain genealogy. Thought to be a descendent of a prominent Llywarch of Rheged, the famed bard Llywarch Hen was assumed, and thus inserted into his genealogy as recorded in Jesus College MS 20. The problem with Llywarch Hen being listed as Merfyn’s ancestor is that all of Llywarch's many sons were known to be killed in battle after Llywarch encouraged their careless behaviour. The poetry of Llywarch tells us:

Four and twenty sons, the offspring of my body,

By my tongue they have been slain.

A little fame is good. They have been lost!

This left him a lonely, bereft and impoverished old man with no heirs. After the devastation of his family in the various wars of Rheged, Llywarch fled over land to Powys. He eventually died as a famously old hermit with no sons. This means Llywarch Hen's descendants were likely not amongst those fleeing to the Isle of Man in the late 7th century, as any that did survive were in Powys. This would seemingly contradict his involvement in establishing a dynasty of rebel pirate Princes on the Isle of Man. The traditional ancestry of Merfyn ap Gwriad therefore can't simply be accepted as that stated in Jesus College MS 20.

A reference to Gwriad in the Welsh Triads confirms the uncertainty of his genealogy. The Welsh Triads mention "Gwryat ab Guryan yn t Gogled" or "Gwriad son of Guryan in the North", counted among the "Three Kings who were the Sons of Strangers". This is normally taken as a reference to Gwriad the father of Merfyn, who was the “son of a stranger” by not being a descendent of Cunedda. It is possible that "Guryan yn t Gogled" is a corruption of Uryan or Urien in the North, making Merfyn and Gwriad possible descendants of Urien, and not his cousin Llywarch. There is another curious genealogical tradition also preserved in Jesus College MS 20 which claims descendants of Urien settled in Wales after the fall of Rheged:

That Ellelw was daughter of Elidyr son of Llywarch son of Bledri son of Mor son of Llywarch son of Gwgon (son of) Ceneu Menrudd who lived for a year with a snake round his neck.

Ceneu Menrudd was son of Pasgen son of Urien Rheged.

This genealogy is chronologically impossible for its stated lineage, it is out of place by significant margins and therefore cannot be correct. It is normally taken as nonsensical legend, but perhaps it preserves some other truth. Interestingly the string of names includes a few familiar ones including "Elidyr son of Llywarch", otherwise relatively uncommon names in Wales. This seems very reminiscent of Gwriad ap Elidyr's genealogy. The traditional descent of Gwriad seems to have a few agreed upon commonalities: Gwriad was a descendent of some Elidyr; who was a descendent of some Llywarch; Gwriad was of the Coeling Rheged dynasty; possibly through some Uryan. If we assume the recorded genealogy of Ellelw ap Elidyr also preserves an alternative traditional genealogy for Gwriad ap Elidyr we find an interesting possibility. Ellelw and Gwriad could be siblings. Hypothetically if we assume that Ellelw ap Elidyr is the sister of Gwriad ap Elidyr, then Gwriad’s new ancestry would be as follows:

“Gwriad son of Elidyr son of Llywarch son of Bledri son of Mor son of Llywarch son of Gwgon son of Ceneu Menrudd son of Pasgen son of Urien Rheged”

To test this new theoretical lineage we can see if known dates of floruits align for the figures of Merfyn Frych 800-ish to Urien 550-ish, assuming generational increments of 25 years on average:

"Merfyn Frych [800] ab Gwriad [775] ab Elidyr [750] ab Llywarch [725] ab Bledri [700] ab Mor [675] ab Llowarch [650] ab Gwgon [625] ab Keneu Menrudd [600] ab Pasgen [575] ab Urien [550].”1

This alternative genealogy of Merfyn ap Gwriad seems to satisfy the dating perfectly, as well as harmonizing both conflicting genealogical traditions from the triads and Jesus College MS 20. It is possible the general tradition of an “Elidyr descended from a Llywarch of Rheged” confused the accurate transmission of Merfyn's genealogy. If we compare the well aligned dating of the alternative genealogy with the dating of the traditional genealogy we see a further problem:

“Merfyn Frych [800] ap Gwriad [775] ap Elidyr [750] ap Sandde [725] ap Alcwn [700] ap Teged [675] ap Gweir [650] ap Dwc [625] ap Llywarch Hen [600]”

The Bonedd lists Llywarch as first cousin and contemporary of Urien and therefore his floruit is also 550-ish (not 600), and his death was roughly 608 earning his epithet “Hen” or “The Old”. Llywarch’s floruit is incorrect by a factor of two generations. This dating of Merfyn’s ancestors further shows the traditional genealogy in Jesus College MS 20 is unlikely to be correct. The Jesus College MS 20 was compiled in the 14th century, 500 years after Merfyn ap Gwriad, it is unsurprising that it could contains some errors. It is possible that a later Ellelw was mistaken for Ellelw ap Elidyr of Manaw, which would explain the puzzling chronological error of the entry, whilst simultaneously preserving and neatly satisfying Gwriad ap Elidyr’s genealogy with the correct number of generations in the correct time period.

It seems almost certain that Gwriad’s father was named Elidyr. The crux of the lineage seems to be in the generation preceding Elidyr. It is curious that it is in this generation, the late 7th early 8th centuries, that the traditional line of Kings ruling Manaw ending in Tudwal ap Anarawd is terminated. There must have been a change of elite at some point after around 725, otherwise Idwal would have inherited the throne from his father Tudwal ap Anarawd which he didn’t. This line of previous Manaw Kings were originally expelled to the Isle of Man from Galloway at an earlier date, probably by an expansionist Rheged. It is more than a coincidence that around the late 7th early 8th centuries an exodus from Rheged to the Irish Sea occurs, and then a new line of rulers is installed on Manaw shortly after.

According to the incorrect genealogy in Jesus College MS 20, Elidyr’s father Sandde is installed as the new ruler of Manaw. He supposedly inherits the kingdom through his wife Celenion ferch Tudwal. The genealogy of this Celenion appears to be a confused copy from an earlier Harleian geneology for Idwal ap Tudwal. An alternate explanation is that an insurgent Rheged dynasty took over Tudwal’s territory around this time through Elidyr’s actual father Llywarch ap Bledri. This event was remembered in tradition as something like “rule was passed to Elidyr son of Llywarch of Rheged”. This was retroactively reinterpreted in the 14th century to be a reference to the famous Llywarch Hen of Rheged, from which the incorrect genealogy was constructed, when in reality Elidyr ap Llywarch belonged to our alternative genealogy descended from Pasgen ap Urien. Llywarch was remembered so prominently in the genealogical memory of Merfyn because he was the first King of Manaw in his lineage.

From this new lineage and rough timeline we can construct a speculative chronological narrative about the exile of this Princely war band. We can also see what their major exploits were whilst marauding around the Irish Sea and their eventual return to Kingship in Manaw and Gwynned.

Of Urien’s sons Pasgen was the younger brother of Owain, Rhun, Rhiwallon, Cadell, Deifyr and Elffin. Most of these sons of Urien were killed in battle leaving only Rhun and Pasgen in the early 7th century. Welsh tradition asserts Pasgen sired numerous sons: Ceneu Menrudd, Gwgon, Mor, Llyminod Angel, Gwrfyw. They went on to found multiple dynasties in Wales. Pasgen is noted in the poetry of Llywarch Hen to be active in the southern portion of Rheged at a place called Yrechwydd, which is thought to be the modern day southern Lake District. In the ensuing chaos that followed Urien’s assassination, Pasgen and his brother Owain were fighting off raids by Dunod from the neighbouring kingdom Dunoting. After Pasgen’s brother Owain died fighting elsewhere, Rhun inherited rule of Rheged. This means Pasgen and his son Ceneu Menrudd were probably based near Caenarvon-Ravenglass when a tactical withdrawal from Rheged may have began, in the wake of Rhun and Rhoath’s perceived problematic actions.

In the Triads Pasgen ab Urien is listed as one of the “Three Arrogant Men” of Britain. This arrogance is unexplained but could indicate disdain for his brother Rhun’s growing relationship with the Angles. Pasgen was known by some of his descendants in North Wales as “the stock of the tribe of the raven kindred”. This motif derived from the mythologised Ravens of Owain ab Urien. Bartrum's Welsh Classical Dictionary asserts that Pasgen was thus considered the true heir of Owain ab Urien. In some genealogies Pasgen is incorrectly recorded as the son of Owain, perhaps due to being considered his true heir. This could indicate an ideological schism between the King Rhun and his brother Prince Pasgen. Perhaps Pasgen’s lingering hostilities to the Angles earned him the status of true heir amongst some supporters, hence the establishing of new lands to the West away from Angle influence. He was also known as Pasgen "of extensive spoil", this indicates he may have gained significant new territory for himself to establish this new dynasty.

However it seems most likely that the rebel faction began its initial stages of departure from Rheged when the Kingdoms inheritance was promised to Oswy and Rhienmellt’s sons by King Rhoath. Rhoath perhaps had no male heirs of his own. It was likely during the early to mid 7th century that the exodus took place. This significant event was therefore most likely during the floruit of Ceneu Menrudd possibly with his elderly father Pasgen in an advisory capacity. Ceneu Menrudd probably disagreed with his cousin King Rhoath about this inheritance plan, perhaps because he had a claim and male heirs of his own. Therefore in about the year 650 Ceneu Menrudd led a significant portion of the Rheged Warrior elite across the Irish sea to seek sanctuary and sponsorship in the court of the High King of Ireland. This may have been inspired by Cadwallon ap Cadfan a generation earlier.

Interestingly and unusually we are given some supplementary information about Ceneu Menrudd in Jesus College MS 20. Ceneu "of the Red Neck" we are told "lived for a year with a snake round his neck" hence its redness presumably. This is reminiscent of the entwined serpent-like chords of a golden torc, like that adorning Merlin in battle: “And in the Battle of Arfderydd my torc was of gold”. The encircling serpent motif was common in ancient European cultures from the Norse world serpent to the coiled Serpent of the Orphic Egg. The Britons also held the serpent as a highly valued symbol. From Pliny's Natural History we learn more about the beliefs of the ancient Druids. "The serpent's egg" was worn around the neck for success in a court of law. (Although the Emperor Claudius killed a native Gaul for wearing "the serpent's egg" in court). We also learn from Pliny that "A vast number of serpents are twisted together" to produce "the serpent's egg", the person who catches the serpents egg must flee with haste "for the serpents will pursue him until prevented by intervening water". The serpent's egg survives into modern day Welsh folklore known as "Glain Neidr" or “Druid Stones” complete with the same creation story "by a congress of snakes". These Adder Stones feature in two tales of the Mabinogion including tales of Peredur son of Efrawg and Owain ap Urien, in both cases the Adder Stones give magical powers relating to invisibility to aid the heroes. Perhaps the reference to Ceneu of the Red Neck wearing a "snake round his neck" was a poetic cultural reference to his disappearance across the Irish Sea driven out by his serpent-like cousin Rhoath "the serpents will pursue him until prevented by intervening water".

There is a similar tradition relating to protective “intervening water” attributed to Merfyn’s brother Cilmin Troed-ddu indicating a possible familial tradition passed down from Ceneu. Cilmin is said to have assisted a magician in stealing the books of a demon. He was pursued by the demon, but saved by leaping over a stream. Cilmin’s left leg plunged into the water and became black. Hence his epithet “Troed-ddu” or “Black Foot”. This is a thematically similar epithet based on a coloured body part much like the “Red Neck” of Ceneu.

Ceneu Menrudd had a son with the relatively uncommon name “Gwgon”. Often families named their sons after their prominent forefathers. For example, Merfyn's son Rhodri the Great had a son called Gwriad after Merfyns father. This Gwriad ap Rhodri had a son called Gwgon. The recurrence of this uncommon name in the hypothesised lineage of Gwgon ap Ceneu Menrudd could be another indicator that this speculative genealogy is the correct one.

Returning to our speculative chronology, in 675 after his pursuit by serpents Ceneu Menrudd’s descendants found themselves in the service of the High King of Ireland Finsnechta Fledach in the Kingdom of Brega. Finsnechta was noted in “The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland” to have won many allies to his cause by way of his generosity. It is this reputed generosity that likely drew the exiled Rheged war band to his court seeking to offer their military service in exchange for payment, much like the Angle foederati in their homeland. In the late 7th century Finsnechta was campaigning in the Northern Kingdoms of Ireland. In 676 he destroyed Ailech and in 679 participated in Battle of Tailtiu against the King of Ulster. There is no mention of any participation by any British mercenaries in these conflicts, but in the Annals of Ulster 682 we get our first mention of the Rheged war band: “The Battle of Ráith Mór Maigi Lini against the Britons”. The entry goes on to imply the Britons were victorious in this battle against the northern Kingdom of Cruithin in which they killed two Irish Princes. It is possible this victory was a part of Finsnechta’s campaign against the northern Kingdoms for which he had hired the Britons. They might have participated in his other battles too.

By this time Ecgfrith had become the King of Rheged and Northumbria. Northumbrian power peaked with Ecgfrith and he was wary of any threats to his reign. It is likely he heard reports of this rogue British warband in Ireland growing in power and prestige amongst the courts of the Irish Kings. Ecgfrith knew about the exile of Cadwallon to Ireland a generation earlier. Cadwallon returned with increased strength and ultimately he conquered Northumbria. This lesson was still fresh in his mind relayed to him by his Father and Uncle who put an end to Cadwallon’s Northumbrian conquest. This period of Ecgfrith’s reign was during the floruit of Mor ab Llowarch. Mor had a rival claim to the throne of Rheged and still probably held open hostilities to his distant cousin Ecgfrith. Ecgfrith was conscious of this growing threat which is why he took unprecedented action.

In 684 two years after the British victory over the Cruithin, Ecgfrith launched an invasion of the Kingdom of Brega. This was in retaliation for harbouring his rival distant cousins. This invasion has long puzzled scholars who characterise it as an unusual and illogical event. No other Anglo-Saxon King had ever launched an attack on Ireland. There is no popular suggested motive for the attack, it even puzzled Bede who similarly offers no motive. In his Ecclesiastical History Book 4 Chapter 26 Bede recalls the event:

Egfrid, king of the Northumbrians, sending Beort, his general, with an army, into Ireland, miserably wasted that harmless nation, which had always been most friendly to the English

Egbert, advising him not to attack the Scots, who did him no harm

Bede goes on to assert that Ecgfrith’s death the next year was punishment for this sin and then further relays that Northumbrian power began to wane after this time as covered in Part One of this series. The entry in the Annals of Ulster recalling Ecgfrith’s invasion only says “The Saxons lay waste Brega, and many churches”. The next year after Ecgfrith’s death, the Abbot of Iona travelled to Northumbria and successfully negotiated the release of 60 Irish hostages. This shows that the Northumbrian motive was probably not an attack on the Irish themselves but a warning against harbouring dangerous British fugitives.

This warning seems to have had the desired effect as after this time the wandering Rheged war band had entered the service of a different Irish Kingdom. They were now fighting for one of Finsnechta’s northern rivals, King of Ulaid Becc Bairrche. The Annals of Ulster record in 697 the Ulaids and the Britons laid waste to Mag Muirtheimne in County Louth, home of a border tribe of Ulidia known as the Conaille Muirtheimne. It is probably in the service of their new King or just as an act of revenge that in 702 the Annals record the new King of Brega Irgalach grandson of Conaing was killed by Britons in “Ireland’s Eye” near Dublin. This new alliance with Ulaid did not last long, much like the Angle foederati they turned on their masters.

The Annals record in 703 the Britons and Ulaid were at war. The Battle of Mag Cuilind was fought in the Ards Peninsula. Perhaps this was a bid to carve out a Kingdom for themselves after sensing a vulnerability in Ulaid. Their bid for control was unsuccessful as the Ulaid were victorious and “the son of Radgann” was slain. This reference to a British warrior cannot be recognised in our genealogy of Princes however this “Radgann” may be remembered in British tradition as “Rhiogan”. This Brythonic name is mentioned as an Irish ruler in the Mabinogion Tale “The Dream of Rhonabwy” featuring Arthur and Owain Rheged.

The last recorded mention of the Rheged war band in the Annals is in 709. Now in the service of King Cellach Cualann of Leinster, they fought in the Battle of Selg somewhere in the Wicklow Mountains. The interesting thing about this final reference is the Brythonic name “Luirg” appearing recorded as one of “Cellach’s Britons”. “Luirg” is the Irish spelling of the Brythonic name “Louargh”. An example of this Brythonic name in use is in the “Subsidy Rolls of Glamorgan” in 1292 “Eynon ab Louargh”. This Brythonic name “Louargh” is an early Welsh spelling of “Llywarch”. Significantly this confirms the presence of a Brythonic warrior named Llywarch in Ireland in the early 8th century. This is the same Llywarch as we have earlier demonstrated as appearing in the genealogy of his Great Grandson Merfyn Frych. This entry could validate our entire speculative theory about Merfyn’s actual descent from Ceneu Menrudd ap Pasgen, who lead the exiled war band from Rheged.

The dating of Llywarch as present at a battle in 709 is slightly early for the theoretical floruit of 725 which we earlier assigned him. The generational increments in this calculation are very flexible. It is very feasible a young Llywarch born in 694 could have been present at the Battle of Selg at the age of 15. It is this Llywarch that in the next decade or so lead the Rheged war band from Ireland and settled on the Isle of Man. This is the event that displaced King Tudwal of Manaw in the early 8th century. This explains why there are no more mentions of the British mercenaries in the Annals of Ulster after this point. It also explains why the rule of Tudwal on Manaw was usurped in his generation not passing to his son Idwal. It also explains why Llywarch was so prominently remembered in the genealogical tradition of Merfyn because he was the first King of Manaw of his lineage.

Llywarch’s grandson Gwriad ap Elidyr erected the Cross of Gwriad at Maughold opposite their old homeland of Rheged. It was from their small and hard won Kingdom on the Isle of Man that Merfyn ap Gwriad won the crown of Gwynned from the line of Cunedda. This restored their royal line back to their former status not seen since the days of Urien. It was possibly also Merfyn Frych that occupied a small part of their former territory of Rheged. Merfyn may have erected the Beckermet Cross near Caernarvon when Northumbrian power waned in the area. Perhaps he even assisted with the annexation of the region by Strathclyde shortly afterwards.

The dynasty of Merfyn Frych would go on to spawn many of the most famous Welsh figures such as Rhodri the Great, Hywel Dda, Owain Gwynedd, Llywelyn the Great and indirectly Owain Glyndwr, the Tudors and according to one genealogy even the modern bard Eminem. The Tudor Kings of England and Wales fulfilled Myrddin’s “Prophecy of Britain” by restoring rule to the line of Coel Hen. The Tudors very own court wizard John Dee, who himself claimed descent from Merfyn Frych, would go on to conjure the very idea and terminology “British Empire” and the fate of the world with it. He gave Queen Elizabeth a book he authored called “The Limits of the British Empire”. This text was inspired by King Arthur’s conquering of otherworldly realms such as “Atlantis” according to Dee. This provided a mandate to reclaim these lost British lands. After his victory at the Battle of Bosworth Henry Tudor was greeted at the gates of Worcester with a poem demonstrating his appeal to ancient British prophecy:

Cadwaladers Blodde lynyally descending,

Longe hath bee towlde of such a Prince comyng,

Wherfor Frendes, if that I shal not lye,

This same is the Fulfiller of the Profecye

It is of further note that many of these traditions from the Old North such as the prophecies of Myrddin seemed to enter the historical record with Merfyn Frych. For example, the Historia Brittonum, which recounts many events in the old north, was written upon the arrival of Merfyn Frych in Gwynedd. It contains a passage which states that it was written in “the fourth year of king Merfyn” hence 829. The Chartres manuscript of the Historia Brittonum begins with this heading:

Here begin excerpts of the son of Urien found in the Book of Saint Germanus, and concerning the origin and genealogy of the Britons, and concerning the Ages of the World.

It is uncertain which son of Urien contributed to the authorship of the Historia Brittonum. Most scholars believe this refers to Rhun, however it could potentially have been Pasgen. Rhun was an educated man of the church, a Bishop who baptised Anglian King Edwin. He was personally close to many of the events described in the manuscript so his credited authorship is logical. It is very probable that Nennius was working from an earlier manuscript compiled by Rhun or his brother Pasgen. This manuscript seems to have landed in North Wales with Merfyn Frych. It would make sense if these materials and traditions recalling and romanticising the glory days pre-exile were transported and preserved in the hands of a rebel Coeling Prince via the Irish sea.

Merfyn was cementing his Northern heritage in the histories of his newfound kingdom. The earliest poems of the northern bards Taliesin, Llywarch Hen, Aneirin and Myrddin were all first recorded around the 9th century, probably in Gwynedd. Merfyn is also directly associated with Myrddin. He is mentioned in "The Conversation of Myrddin and His Sister Gwenddydd". One tradition in 16th century manuscript The Chronicle of Elis Gruffudd asserts that Merfyn Frych is the father of Myrddin, although this apocryphal text is likely inspired by a confusion of similar names. These traditions: Taliesin, Myrddin, Arthur and Urien were almost certainly transferred by a literate Coeling Rheged elite, whether by sons of Llywarch Hen or Urien. Merfyn’s descendants long held the memory of their northern roots as exhibited by the twelfth century Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd’s boastful poem Gorhoffedd, in which he seeks to emulate the famous bard Myrddin “Music of praise such as Myrddin sang”. Hywel recounts his own journey to Carlisle, in what he still poetically considers Rheged, the land of his fathers namesake:

How far from Ceri, Caer Lliwelydd,

I rode a bay mount from Maelienydd,

Far as Rheged, by night and by day.

Note from Aurochs: after discussion with @p5ych0p0mp, With a 28 year generation Urien’s Birth is closer to a more satisfactory 520ad, giving the list here "Merfyn Frych [800] ab Gwriad [772] ab Elidyr [744] ab Llywarch [716] ab Bledri [688] ab Mor [660] ab Llowarch [632] ab Gwgon [604] ab Keneu Menrudd [576] ab Pasgen [548] ab Urien [520]. Generally a 28 year generation is more satisfactory in ironing out gaps between late fathers and early fathers. While a difference of 3 years per generation may not seem like much, after only 9 generations it compounds to an entire missing generation.

Great article! I found the genealogical arguments particularly interesting.

Awesome! So spoiled for 'content'. Now on to Part 3!